Walking into Multiplicity’s studio, it’s immediately clear that this is no average architectural practice. The studio occupies part of the old Henderson’s Shirt Factory on Brunswick Road, but despite the location in Melbourne’s increasingly hip inner north, it’s the antithesis of the inner-city designer archetype. There’s no typographically Zeitgeist-grabbing signage, no recognizably expensive furniture, no minimalist workstations – there are just people and, to be frank, lots of “things.”

Interior designer Sioux Clark and architect Tim O’Sullivan, the practice’s founders, openly refer to themselves as magpies. They have a keen eye for found objects and preloved materials and, crucially, a rare and extraordinary knack for recognizing the potential in what to most of us is merely the detritus of industrialized society. It plays out in their work and it defines their workspace.

It’s marvellous what a difference Milo makes, 2005, Melbourne: The main bedroom boasts a wall made from recycled timber in a composite arrangement.

“The studio is entirely constructed of recycled material and found objects, save for the timber frame, which will eventually be reused when we renovate,” says Sioux. There’s a wall clad in a green fibreglass roofing product which was sourced via the Trading Post from an old Myer warehouse in the western suburbs, an old map of Royal Park gleaned from a local tram stop, Baltic pine sleeper bench seats retrieved with a plumber’s ute from a nearby railway siding, and two stainless steel storage cabinets found in the back lanes of Parkville and affectionately named Roger and Randal after prominent Melbourne-based architects, who happened to live thereabouts.

This predilection for collection and appropriation is only one part of the architectural story – in the midst of the magpie’s nest, Multiplicity crafts contemporary homes of singular refinement – but it pervades their work in different ways and at different scales: for instance, the found object may be a railway sleeper or a cache of roofing sheets, but it may also be an entire building. Multiplicity’s deft hand at adaptive reuse was arguably what first put them on Melbourne’s architectural map, and their commitment to retaining existing structures (and preserving embodied energy) where other practices might take a more blasé approach to demolition is still central to their sustainability-focused philosophy.

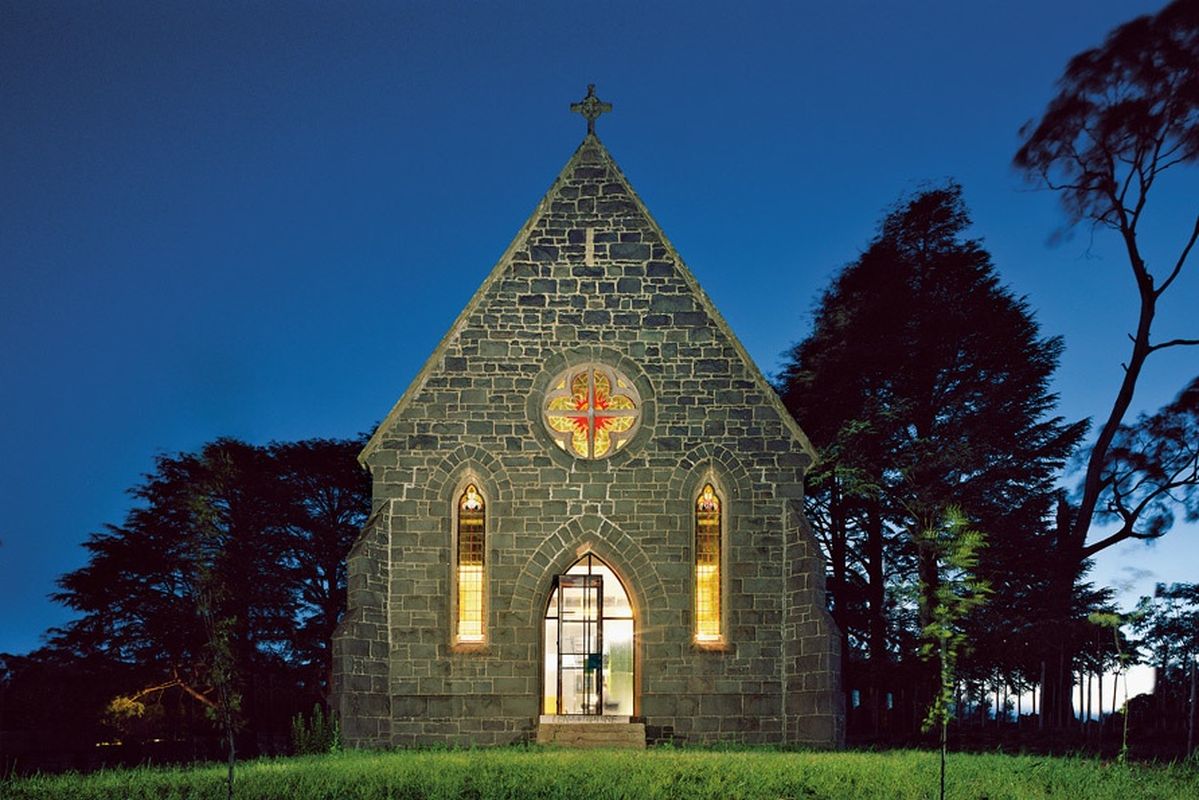

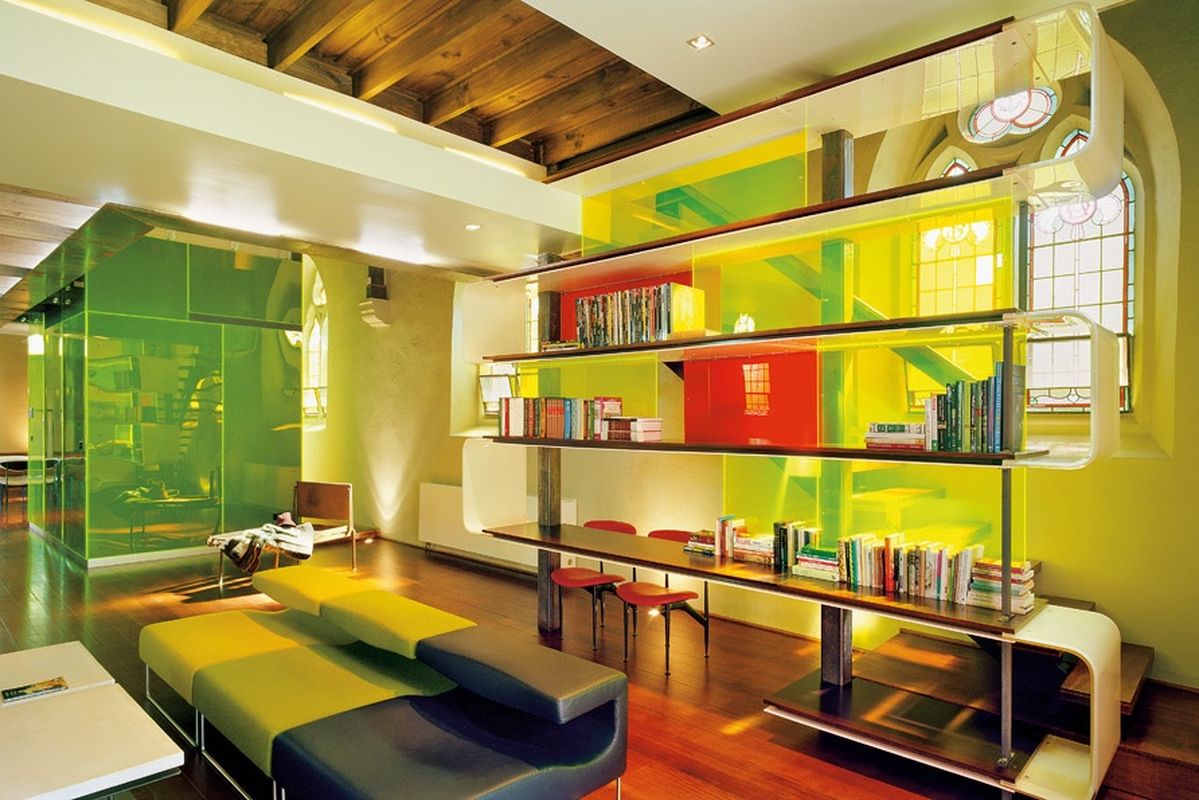

The Church, 2004, Vic: The transparency of the panels honours the original interior volumes.

Image: Emma Cross

An early project, It’s Marvellous What a Difference Milo Makes (Houses 46), neatly encapsulates Multiplicity’s modus operandi. (Not to mention their penchant for intriguing project names, this one inspired by the pending arrival of the clients’ baby boy, Milo, and the resulting urgency in completing design and construction. We’ll call the project Milo for short!) Occupying a two-storey 1940s warehouse in Richmond, it’s a bewitching example of adaptive reuse. The existing building’s tiny footprint (6.5 metres by twelve metres) meant that the new home had to expand upwards. Four levels are linked by stairways carefully positioned to take visitors and occupants on a journey through the house, and a fourteen-metre lightwell draws natural light deep into the building. Concrete and steel elements play off the industrial heritage of the building and two walls clad in old timber cupboard doors add to the sense of history.

Despite the theme of textural materiality, and Tim’s declaration that the practice has “a passion for raw materials,” there’s another, quite different but very important element to be considered here. Just like real magpies, Sioux and Tim are drawn to shiny things. Transparent, translucent and reflective walls, and screens and surfaces that filter, reflect and refract light can be found in many of their houses. In Milo, this comes in the form of webglass – translucent sheeting that transmits soft light and reveals the structures and patterns of the building itself (what Sioux referred to in a previous Houses article as “the builderly rhythm of studwork” and “the inherent beauty of the frame”).

In the Church, another of Multiplicity’s notable early adaptive reuse projects, the use of green transparent acrylic panels brings a subtly 1980s DayGlo vibe to the unlikeliest of places – a church in a small town in rural Victoria. In some ways, it’s a high-impact design strategy: the panels and other insertions are emphatically new and modern. But, in other ways, it minimizes the impact of the conversion from public building to house: the transparency honours the interior volumes that the architects inherited, and preserves their wonderful sense of spaciousness and the penetration of natural light.

Sally and John’s, 2009, Melbourne: All the familiar material touchstones are there – warm timbers, concrete, translucent sheeting.

Image: Emma Cross

If the church project celebrates something from the 1980s, Sally and John’s, an alt-and-add to a large Federation residence in Carlton, was all about destroying any memory of that decade – specifically, a 1980s addition housing a mock-Colonial kitchen and other atrocities. Looking at the photographs of the new extension, the familiar material touchstones are there – warm timbers, concrete, translucent sheeting – and also the sensitivity to pre-existing buildings. The extension provides a bridge between the garden and the original building, its detailing offering a reinterpretation of the original Federation design.

Chrystobel, 2009, Melbourne: The bespoke approach is perhaps the defining characteristic of Multiplicity’s work.

Image: Emma Cross

Similarly, at Chrystobel, a renovation project at an Arts and Crafts house in suburban Hawthorn, detailing in the new addition provides a “designerly” response to the heritage of the house. It’s exquisite. “We have an obsession about detailing, and about never leaving it up to someone else to resolve a juncture,” says Sioux. “We don’t really have a filing cabinet for standard details,” adds Tim. It’s an approach that the marketing minded would call bespoke, and it’s perhaps, above all else, the defining characteristic of Multiplicity’s work. Sometimes it might require careful designing and making, other times it might provide the opportunity for a found object to reveal its potential, but every time it’s about aesthetic merit.

Making sense of Paola and David’s, 2009, Melbourne: Multiplicity’s signature materials palette marries with strong black, green and red elements.

Image: Emma Cross

This is certainly the case at Making Sense of Paola and David’s. A new home, designed by another party for a site in Richmond, it was already under construction when Multiplicity was engaged to fully document and rework the interior (a found object of a different kind, then). The resulting residence marries the signature Multiplicity materials palette with strong black, green and red elements.

Whether they are working on a new home or adapting an existing building, attention to detail and loving concern for every decision are clearly hallmarks of Sioux and Tim’s approach to residential design. And while Tim jokes about spending hours on a single detail only for Sioux to walk over, look at the drawings and say, “No, that’s not right!” it’s very clear, when listening to them talk about projects and ideas, how important collaboration, interrogation and discussion are in the studio. Above its front door, faded gold lettering reads EMPLOYEES’ ENTRANCE and it seems an apt inscription: the Multiplicity team isn’t here to impress visitors with designer bling – it’s too busy making things.

Source

People

Published online: 6 Jan 2012

Words:

Mark Scruby

Images:

Emma Cross

Issue

Houses, October 2011