PHOTOGRAPHY Iredale Pedersen Hook

REVIEW Narelle Yabuka

An aerial view of the Tjuntjuntjara community housing project, showing the spectacular desert country.

Existing conditions at the Tjuntjuntjara community, showing the verandah-living of the ex-Cavalier Transportable. The new housing supports a similar pattern of use.

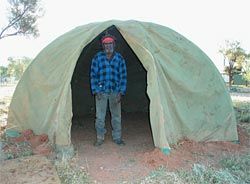

Dome tents were also part of the existing housing.

Details of the landscape at Tjuntjuntjara, understood by the architects and community as an important part of the project context.

Extensive consultation was key to

Iredale Pedersen Hook’s design process

for the Tjuntjuntjara community

housing in the Great Victorian Desert.

Architects working in the area of Indigenous housing, particularly when it is remote, undoubtedly find themselves partaking of a discourse distant from, and at times even diametric to, that surrounding the Anglo-Australian model. It goes without saying that they will actively negotiate a crucial middle ground between spatial and sociocultural dimensions. Furthermore, they will most likely search for a balancing point between the substantial weights of pragmatic and metaphysical considerations. Yet despite the momentousness of these explorations, they may conclude, as did Finn Pedersen of Iredale Pedersen Hook (IPH) after working in Western Australia’s remote Tjuntjuntjara community, that a house is only a small part of a community. “It is literally a piece of infrastructure.”

›› The many challenges inherent in the design, procurement and discussion of housing for Indigenous Australians have only recently benefited from a perspective beyond that of those who have traditionally “provided”. Publications such as Settlement: A History of Australian Indigenous Housing and Housing Design in Indigenous Australia (from the TAKE series) have begun to flesh out these challenges, highlighting, among a myriad of other considerations, the ambiguous meanings attributed to such critical terms and notions as “camp” and “settlement”.1

›› Indigenous Australian domiciliary patterns do not conform to Anglo-Australian house types and, furthermore, are as varied as the user groups. This indicates that there is no single correct architectural prototype for Indigenous housing. Rather, it has been found that people should be at the centre of their housing process – “determining their own needs, being involved in planning and design, having a role in funding, and implementing the steps toward delivery of appropriate and sustainable living environments.”2

›› IPH adopted extensive community consultation as a critical element of the design process for eight houses at the Tjuntjuntjara community, situated 12 hours’ drive east of Kalgoorlie. The people of the community were displaced from their homelands by the British atomic testing at Maralinga in the 1950s. A camp was established at Tjuntjuntjara in the mid-1980s after a permanent water source (in the form of a lens aquifer that is recharged by rain) was discovered within the spinifex desert landscape.3 Survivors launched a compensation claim against the British Government, which, in recognition of colonial atrocities, precipitated funds. Tjuntjuntjara is now home to a number of world-renowned artists working in paint and wood (carving). Revenue from the art sales, often in Europe, generates a second income stream.

IPH’s process-based proposal for the derivation of housing forms was selected by the community from a range of four consultancy options, despite being the most intensive and expensive. Avoiding prescription and temporarily sidelining many of the concerns of housing “hardware” (such as materials or construction solutions), IPH embedded their initial consultation firmly in the realm of housing “software” – ties to land, patterns of spatial use, family relationships and genealogies, and cultural and spiritual beliefs.4 Anthropologist Sarah Yu formed part of a multidisciplinary consultative team that also included an engineer and community staff members. Yu’s appointment in particular was a strategic one, given the expectation that the community’s women would have difficulty speaking with male consultants.

With translation provided by community members, a series of three intensive workshops, each two days long, were undertaken. Family by family, documentation was created detailing genealogies and kinship, and individual family needs and aspirations. After this, IPH produced a series of sketch designs, which they presented to each family as cardboard models, and enacted walk-throughs. Two designs were eventually chosen – a centric plan form with a breezeway living area (able to support a fire), and an L-shaped plan form (as commonly found on pastoral stations, with bedrooms opening to a verandah).

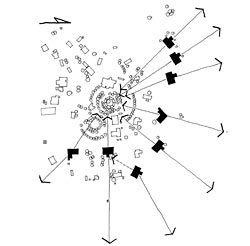

Prior to the housing construction, people were camped around the community in humpies, tents and corrugated iron shelters. A central meeting area (where tensile shade structures have now been erected) would be used for whole community consultations, around which people would sit in a ring. The consultants discovered that the position in which people sat on the ring indicated the direction of their country. The location of sites for houses would also come to respect this method of orientation, at times with the tweak of a slight rotation to address immediate family – for example, a son’s or daughter’s house. The siting of the structures within the community thus expresses a mapping of culture, relationships and place, just as culture, relationships and spiritual concerns (along with an extensive range of pragmatic considerations, including buildability and maintenance) would come to be embedded in the house forms themselves.

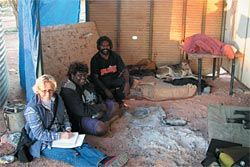

Extensive community consultation was a critical element of the design process.

Anthropologist Sarah Yu consulting with community members.

Tjuntjuntjara housing site plan.

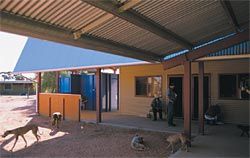

The central meeting area at Tjuntjuntjara is protected from the sun by an arrangement of tensile shading devices.

Elevation of housing Type A.

An example of Type B housing.

›› In essence, the house forms were conceived as having two parts – a roof shelter and a windbreak – able to support both traditional outside camping/living patterns and “internal” living patterns. Plywood panels at the corners of verandahs, for example, create small windbreaks, or outdoor rooms, where a bedroom “camp” may be installed. Movement between communities and the resulting population fluctuation (due to events ranging from a death to a football match) necessitate flexibility in the accommodation capacity of the house, as extended family is never turned away. This means the house must function as a shared facility, which throws notions of ownership into question. As such, lockable bedrooms might become repositories for valued goods, for example, being slept in only during very cold weather.

Another cultural issue – one among many – that affected the planning approach of the architects was the mother-in-law/son-in-law relationship. It is forbidden for these two to meet or talk, so multiple points of exit must be provided and corridors avoided. Spiritual beliefs, such as a fear of night-time sorcery, seem to encourage the covering of bedroom windows with heavy blankets for protection from external view. Along with the directional approach to siting, this presents a significant challenge to passive solar design.

It makes for problematic terrain for architects, but what’s more, it cuts to the chase of the challenges facing consultants to Indigenous communities. Spiritual issues may not be open for discussion, for instance. “Good consultancy in Aboriginal communities can’t be rushed, it can’t be prescribed, and you won’t necessarily receive a simple answer to a question,” explains Pedersen. “You must try to decipher, amongst that field of information, which are the important elements for the community.”

›› There is a visible restraint at Tjuntjuntjara from any attempt to impart notions of what an “Aboriginal” architecture might be, other than a response to the known functional and cultural/spiritual requirements of this community. Architectural expression is more a result of pragmatic drivers – designing for climate, for remote building approaches, for sustainable maintenance, for health and safety, for service acquisition and delivery design, and for material use.

The demise of ATSIC casts some doubt over the ability of Indigenous communities to continue to exert such a degree of control over their own housing processes. The required specificity to community that seems intrinsic to Indigenous housing would perhaps best be served by a continuation of the intensive process illustrated at Tjuntjuntjara. Exploration rather than prescription would perhaps be most useful to communities who continue to inhabit a cultural climate that shifts while it endures.

Narelle Yabuka is a lecturer in interior architecture at Curtin University of Technology and a freelance writer on matters of architecture and design.

The siting of the buildings within the community responds directly to a mapping of culture, relationships and place.

The outdoor spaces of a Type A building. The structures are designed to be simple and robust to suit the harsh environment.

Looking towards the small cluster of buildings forming the Tjuntjuntjara community.

The amenities of a Type B block.

An interior view of a kitchen and living area, a year after construction of the new housing was completed.

1 P. Read (ed), Settlement: A History of Australian Indigenous Housing (Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2000) and Paul Memmott (ed), TAKE 2: Housing Design in Indigenous Australia, (RAIA, Canberra, 2003).

2 G. Barker, “More than a House: Some Reflections on Working with Indigenous Clients on the Housing Process”, in TAKE 2: Housing Design in Indigenous Australia, pp. 98–105.

3 The site, around 650 kilometres east-north-east of Kalgoorlie, was also considered a gateway to the community members’ homelands to the north.

4 Paul Haar uses the terms “hardware” and “software” in his essay “Community Building and Housing Process: Context for Self-Help Housing” (TAKE 2: Housing Design in Indigenous Australia, pp. 90–97).

The latter, he writes, encompasses the great potential, challenges and difficulties inherent in self-help housing.

TJUNTJUNTJARA COMMUNITY HOUSING, GREAT VICTORIAN DESERT, WA

Architect

Iredale Pedersen Hook—project team Finn Pedersen, John Knuckey, Caroline di Costa, Adrian Iredale, Ross Brewin, John Belviso.

Structural consultant

Brian Nelson (Capital House Australasia).

Builder

Barry Baxter (Urban Building Company).