Review Naomi Stead

Photography John Saeyong Ra, Emile Wamsteker, Ari Burling

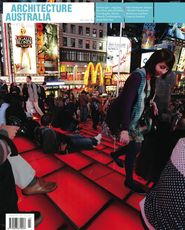

N°1 Both viewing platform and stage, the TKTS booth provides a moment of pause within the frenetic activity of Times Square.

N°2 Aerial view of Times Square. The ticket booth is housed underneath the translucent tiered steps.

N°3 East elevation from Choi Ropiha’s winning entry to the international competition.

N°4 The new structure forms a backdrop to the statue of Father Duffy.

N°5 The “theatre” of Times Square. The new seating/steps are lit from below.

N°6 Detail of the steps and handrail of the all-glass structure.

N°7 The business end of the facility – the ticket booth is housed in a fibreglass pod beneath the steps.

It was pretty big news at the time, in architectural circles throughout Australia. Back in December 1999, the announcement was made that John Choi and Tai Ropiha, two young architects from Sydney, had won the international competition for a new TKTS booth in New York’s Times Square. Part of the newsworthiness must have been a flash of parochial pride – the competition was, after all, the biggest that had ever been held in New York at that time, with 683 entrants. Winning it was a mighty coup, and even more so for a pair of architects from the other side of the world, entering their first international competition. But as soon as you saw the scheme, any jingoism evaporated. The architectural idea was so simple, elegant and absolutely right for the location and the brief that it seemed almost inevitable it had won. As with all great design, looking at it made you think: of course. It is obviously right. Naturally these things are only ever obvious in hindsight, and like the concealed, furious paddling by which the swan appears to glide so effortlessly, coming up with an idea that seems inevitable is a difficult and often laborious task.

Equally strenuous can be the process of getting a great idea actually built, and this one was no exception. Political, economic and administrative changes, the appointment of local architects Perkins Eastman to develop and document the design and supervise construction (“inspired” or “based on a concept” by Choi Ropiha, as the press coverage has all carefully said) and a major contractor going broke all meant that it is not until now, nearly ten years later, that the project is complete and open, having been inaugurated by Mayor Bloomberg on 16 October 2008. Choi Ropiha are philosophical about their limited role in the actual realization of the building, arguing that high-profile public projects are almost always fraught, compromised and longwinded, and this one was no different. They were kept informed throughout the process, but they had little direct input after the first stage. Perkins Eastman took the project on a swerve towards high technology, with an all-glass structure of beams and load-bearing glass walls. The actual booth itself is housed in a fibreglass pod, fabricated by a yacht builder and slipped into the outer shell. The level of finish is sleek, and Choi Ropiha are diplomatic about the overall end result – saying that while of course there are things they would have done differently, it is a pleasure and a relief to see that the original idea was robust enough to come through largely intact.

The competition scheme proposed a terraced, inclined plane of glowing red stairs, lit from within, splayed outward to follow the diverging lines of Broadway and Seventh Avenue, and with the ticket booth tucked underneath. The design completely reframed the existing statue of Father Duffy, World War One chaplain and local hero, releasing it from behind the railing that had so cramped the previous ticket booth, and bringing what had become an “invisible” monument out into active public space. (The final plaza design was the work of PKSB.) The previous TKTS office had been constructed in 1973 by the Theatre Development Fund, as part of the City administration’s attempt to spruce up what was then one of the most seedy and dangerous parts of town. The booth, which sells cheap tickets for same-day shows, was an immediate and spectacular success, bringing a steady stream of locals and tourists who in the years since its opening have purchased a staggering 51 million tickets. But the first TKTS booth had only been intended as a temporary measure, and as Times Square itself changed dramatically, and the lines of queuing ticket-buyers sometimes numbered up to three thousand and spilled into the adjoining streets, there was a need for renewal.

The Van Alen Institute, which organized the original competition on behalf of the Theatre Development Fund, describes Times Square as “the most illuminated, walked upon, televised and recognized intersection in New York City… familiar even to those who have never set foot there – the quintessential symbol of the city that never sleeps.” The Choi Ropiha scheme took this riotous cacophony, vibrancy and speed, and proposed a moment of pause within the rush, a viewing platform that is equally a stage. The associations are richly layered – the brilliant colour suggests red carpet and red theatre curtains, but the form also suggests the bleachers of audience seating, as well as a stage set – like a high-camp musical, it invites you to don your tux or feathered headdress and try out a few high kicks. Over the course of a long, cold February evening, as a slow dusk fell over the project, it was remarkable to observe the transformation – as the light dimmed, the stairs began to glow and the sense of theatricality and excitement palpably grew.

Manhattan Island has one of the most magnificently universalist, relentless urban grids of any city, and this rigour is most keenly revealed where the pattern is broken, where it is crossed by the dramatic oblique slash of Broadway. The interference caused when these two systems intersect creates some wonderful moments in the city – an occasion for a park like Union Square, a wedge of building like the Flatiron. At Times Square, Broadway and Seventh Avenue come almost exactly into phase, meeting to produce a “bow tie” of streets intersecting at an acute angle, with two thin wedges of public space left in between. There are few voids in New York’s urban block, as Choi observes – “There are not many places where the grid relents and gives you some breathing space” – and so they were loath to fill the gap with yet another building. The intention was thus less to make a “building board” and more to conceive the project as urban design, opting for something grounded. In any case no conventional booth could possibly compete with the scale and visual cacophony of the surrounding signage, nor with the volume and speed of circulation through the site. We know this because there is indeed another such booth. In the reflected position on the opposite side of the “bow tie” is a US Armed Forces recruiting station. While even this has been glammed up, with an American flag in strips of neon across one wall, its rectilinear box form shows by contrast just how clever the TKTS booth is – not a closed container of space, massively outscaled by the surrounding skyscrapers, but an inclined platform that appropriates this vertical slot of space for itself, providing a floor, then taking the surrounding billboards as its interior walls. In this sense the project turns the city inside out, reversing the figure ground so that the square becomes an interior, of infinite height, lined with flickering images. Disconcertingly, some kind of reversal also occurs in the horizontal dimension – looking at the skyscrapers reflected at your feet is strangely like standing on a glass platform above an infinite void, looking downward into the sky. It is a vertiginous feeling, slightly alarming but exhilarating, perhaps a little like the feeling of winning a competition like this or, later, of finally seeing it built.

Dr Naomi Stead is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Queensland.

TKTS, TIMES SQUARE, NEW YORK, USA

Architect

Choi Ropiha, Perkins Eastman, PKSB—concept design Choi Ropiha; design development and executive architect Perkins Eastman; plaza architect PKSB (William Fellows Architects).

Engineer

Dewhurst Macfarlane and Partners, DMJM Harris, Schaefer Lewis Engineers.

Construction

Lehrer, D. Haller, IPIG, Saint-Gobain/Eckelt Glas, Merrifield-Roberts.

Project partners

Theatre Development Fund, Times Square Alliance, Coalition for Father Duffy, The City of New York.

Photography

1–4, 7 John Saeyong Ra

5 Emile Wamsteker

6 Ari Burling