Joel Sanders is an architect who does not like to be stereotyped. This is evident in his approach to practice, which spans exhibitions, buildings, teaching and publishing. His first book to capture artificial constructions was Stud: Architectures of Masculinity, which looked at the making of male identity through architecture. His latest publication, Groundwork: Between Landscape and Architecture, written with Diana Balmori, also looks at the construction of stereotypes, this time in the binary of landscape and building. During a visit to Melbourne in July 2012, where he was a keynote speaker at the Audio Architecture symposium, Joel Sanders spoke with Architecture Australia editor Timothy Moore about the dilemma of man-made dualisms in the architectural world.

Timothy Moore: Your body of work is tied together by your ability to recognize and harness latent forces in the environment. First, in the 1990s, you were the editor of Stud: Architectures of Masculinity, which looked at the performance of gender. Then came Groundwork: Between Landscape and Architecture, written with Diana Balmori, which looks at the splintering of landscape and architecture from a historical perspective and at ways to bind the forces of nature and humankind back together by ignoring the binary all together. Groundwork begins in North America in the nineteenth century and talks of an Anglo-American conception of the landscape as “wilderness.”

Joel Sanders: The overall objective of Groundwork – the promotion of new, inventive modes of interdisciplinary practice – can only be achieved by first understanding and transcending the deep-rooted cultural, ideological and disciplinary prejudices that have brought us to where we are today. In my introductory essay, I examine the architecture-landscape divide from a cultural and historical perspective and argue that this split can be traced to another deep-seated yet suspect Western polarity that opposes humans and nature and, as a consequence, buildings and landscapes. While these attitudes date back to antiquity, one version of the human-nature dualism finds its home in an influential body of thought that emerged in nineteenth-century America [around] wilderness. A first generation of environmentalist thinkers and activists like Henry David Thoreau, Charles Muir and Theodore Roosevelt, all men active during the second half of the nineteenth century, were confronted with an intimidating prospect not unlike that which we face today – the disappearance of wilderness.

TM: The loss of wilderness is not only a tale of a rupture between humans and nature, but also hints at a divide along gender lines.

JS: Correct. If nature was traditionally conceived of as an unruly woman that needed to be subdued and cultivated through the labour of men, wilderness thinking then cast nature as a virgin in desperate need of male guardianship; [there was the idea that it] needed to be conserved and protected from the ravages of industrial civilization. Not only did wilderness thinking give birth to the American environmentalist movement, but it also shaped the evolution of landscape and architecture in America from the nineteenth century until today. Its dualistic conception of people and nature only reinforced the age-old Western conception of the building as a man-made artefact qualitatively different from its ostensibly natural surroundings. In turn, this way of thinking impacted professional conduct. This was reflected in the segregation of architects and landscape architects into parallel professional organizations: in 1899, at the height of the wilderness movement, a new professional academy, the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) was established. Wilderness core values not only resulted in dual design professions but it also shaped design approaches: by positing that the human is entirely outside the natural, wilderness presents a fundamental paradox: how to reconcile the ideal of untouched nature with the imprint of human design. The result is a deep and persistent suspicion of designed nature that still endures today.

Central Park in Manhattan was designed by Frederick Olmsted as a natural oasis inscribed within the metropolis.

Image: Erik Daniel Drost

TM: A critical juncture in this narrative is Olmsted’s design for Central Park in New York City.

JS: Frederick Law Olmsted, the founding father of American landscape architecture, subscribed to a design approach that was influenced by wilderness peers like Emerson and Thoreau. Olmsted conceived of projects like Central Park as a natural oasis inscribed within the dense metropolis, a place that offered weary urbanites refuge from the onslaughts of the industrial city. Nature’s rejuvenating effects were made possible through the visual contemplation of nature. Olmsted artfully composed topography and trees to screen out the offending urban environment. In projects like Central Park and The Riverway in Boston, Olmsted obscured not only the surrounding city but also all traces of human effort – the art and technology that made the realization of his massive urban infrastructural projects possible. He accomplished this by employing a pastoral vocabulary that even today viewers assume to be “natural.” My point is not to underestimate Olmsted’s extraordinary achievement, but rather to say that his legacy persists today: it has resulted in a default identification between nature and the picturesque landscape that encourages designers to mask rather than celebrate designed nature.

TM: There was a shift in the mid-twentieth century towards an ecological way of thinking within [landscape] architecture as a means of creating an integrated system of nature and humankind. Did this upset the binary?

JS: This way of thinking was still shaped by wilderness or an oppositional way of thinking. A struggle to resolve the supposed incompatibility between nature and design is evident in the ecological design approach advanced by University of Pennsylvania professor Ian McHarg in his influential book Design with Nature. In 1969, Olmsted’s worst predictions had been realized – rapacious capitalism aided by remarkable technological advances had tipped the precarious balance between nature and civilization. It was the responsibility of landscape architects to correct the resulting environmental causalities – America’s polluted, slum-ridden cities. But how? McHarg appealed to the natural sciences: he pioneered an ecological methodology that encouraged designers to consider a range of interconnected environmental factors – climate, water, flora and fauna – a system that is still immensely influential today. Nevertheless, his proposals, generated through an approach grounded in the supposedly objective logic of the natural sciences, largely evaded design. His regional masterplans were too large and abstract to engage with issues of form, space and the human body in a way traditional garden designs once did.

TM: What is the legacy of Olmsted and McHarg, two designers that were constrained by wilderness?

JS: American practitioners have inherited values that continue to shape design practices today. [These values include] a dualist way of thinking that views nature as a passive, vulnerable entity that must be protected from the predatory interests of humans, including architects and landscape architects; a professional bias against designed nature, often dismissed as a frivolous pursuit affiliated with residential gardening, decoration and feminine artifice; and a preference for a large-scale problem-solving based on a deterministic design approach justified by science.

TM: In Groundwork, you provide case studies to overcome this binary. You present three trajectories.

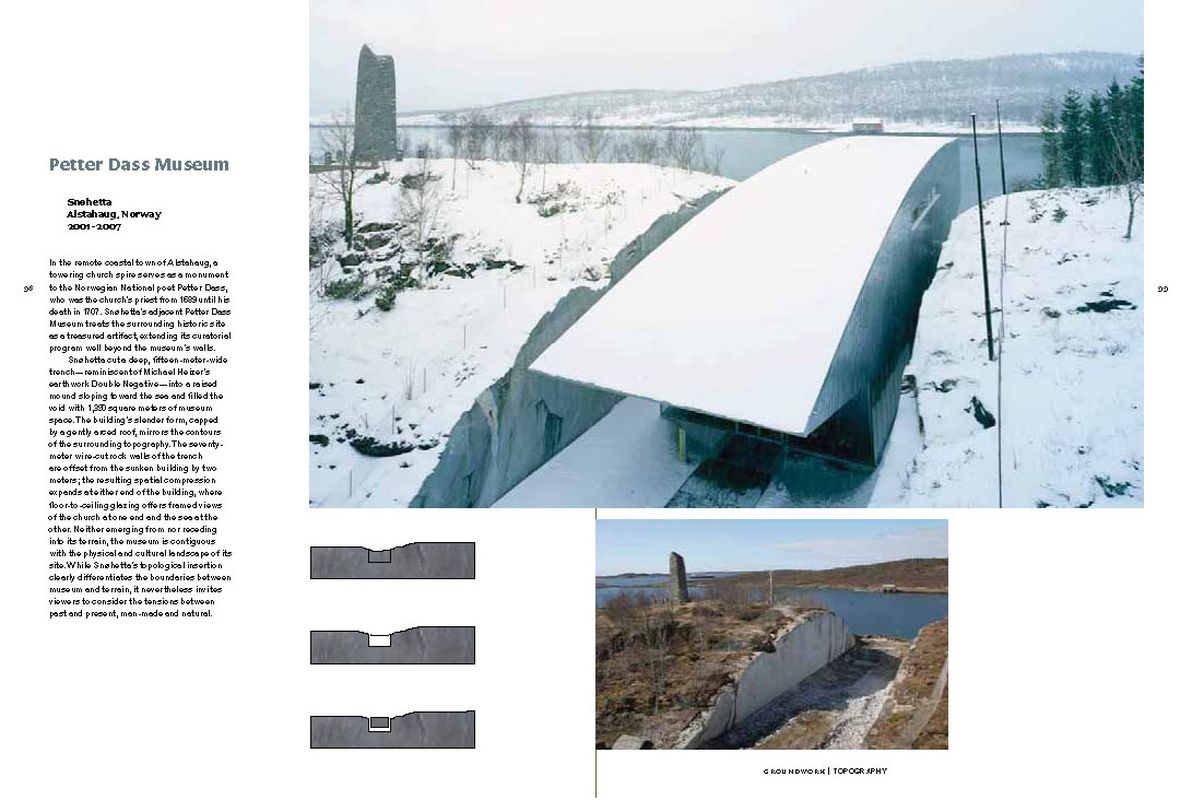

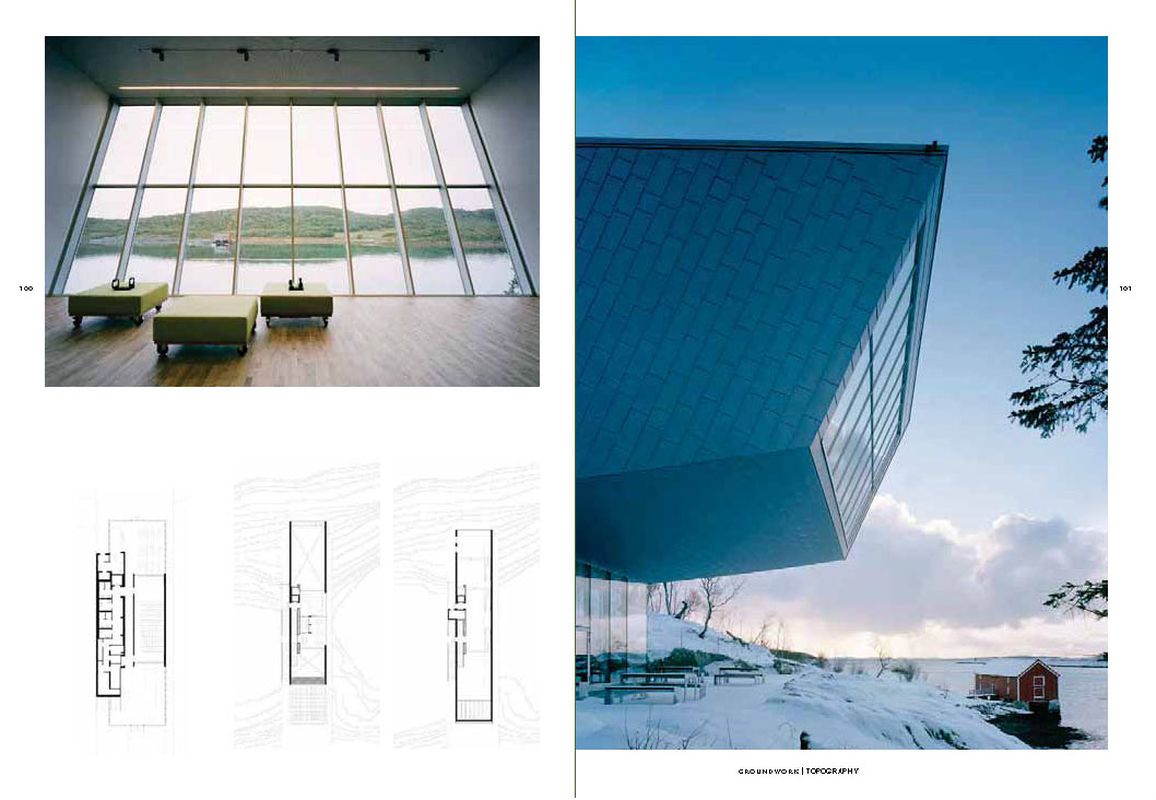

JS: The three ideas are a way of organizing overlapping trends but they are not discrete. The first is called topography. Topographic designers reject the paradigm of the object-building that sits discretely on the land. Instead, topographers manipulate the ground to blend building and landscape, treating built form as inhabitable landform. The second is ecology and champions ecological practitioners embracing a robust design vocabulary – one that resists the feel-good mentality prevalent in so much green design. Ecological designers are instead interested in unleashing the creative potential of sustainability, employing green principles at different scales – from the surfaces of buildings to entire masterplans. The third category of biocomputation explores the work of a new generation of digital designers who script digital codes that exploit the computer’s potential to emulate living systems by using algorithms that reflect the complexities of biological processes.

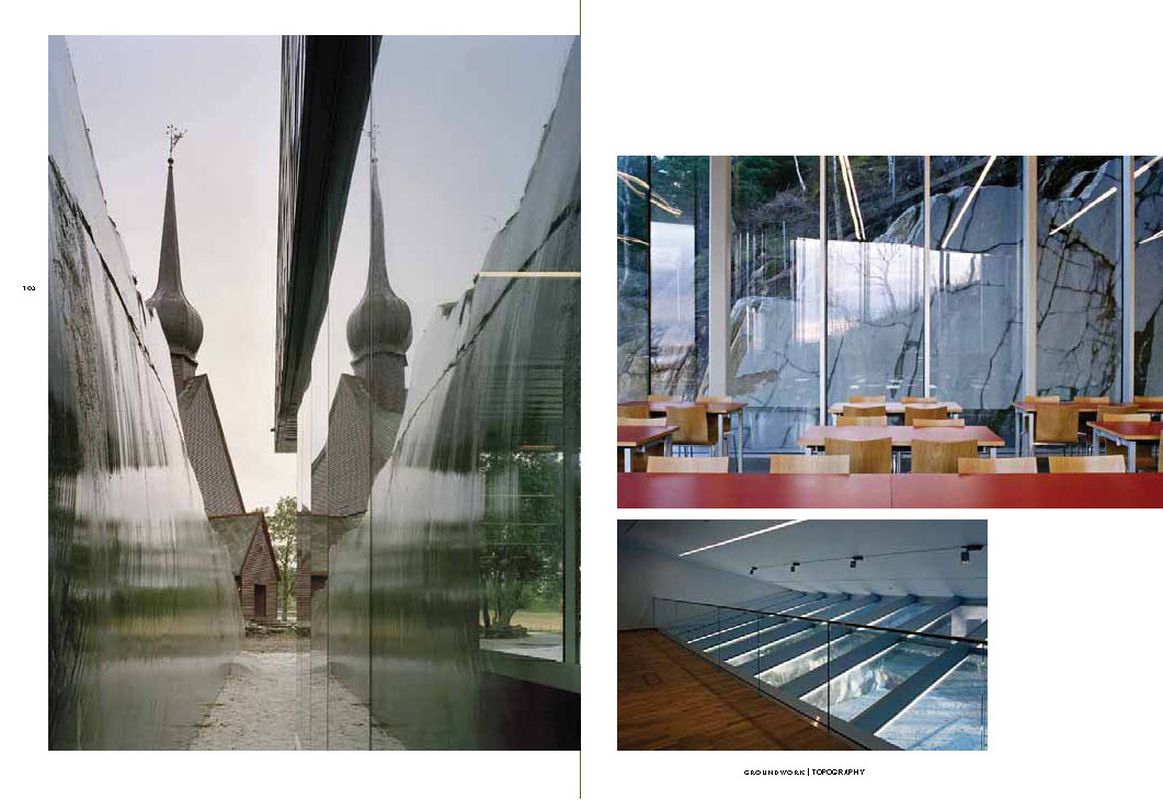

Lateral glass walls capture exterior and interior reflections at the Petter Dass Museum in Norway, superimposing images of nature and architecture.

Image: Åke E Lindmann

TM: In the book, you categorize Snøhetta’s Petter Dass Museum in Norway as topographical. But it is not necessarily working with the landscape in a way one would expect. In fact, there is a stand-off. A huge cut is made into the landscape and the building replaces the mass removed, except for a two-metre gap between the sheer rock face and the glazing.

JS: Snøhetta highlights rather than elides the distinction between building and hillside by cutting a deep trench and filling the void with a discrete wedge-shaped building; its arched roof mirrors the contours of the surrounding topography. Although Snøhetta’s topological insertion clearly differentiates the boundaries between museum and terrain, it nevertheless asks viewers to consider the tensions between them: lateral glass walls capture exterior and interior reflections, superimposing images of nature and architecture.

TM: It is sublime, that architecture can add to and be separate from the landscape. This is the confrontation. Yet the false binary of architecture and the landscape, and nature and humankind, is something everyone in the architectural community is very familiar with. But in parallel, we have separate courses and professional bodies for landscape architecture and architecture. How do you respond to this in your own practice?

JS: Rather than thinking of the landscape as an afterthought in the design process as architects are prone to do, from the moment we put pen to paper, or keyboard to computer screen, our objective is to come up with unified spatial and programmatic concepts that treat interior and exterior as linked entities that shape human experience. We are interested in exploring the interface – the seam where inside and outside come together – at the scale of the human body. That’s where it gets interesting. All of my career I have been interested in the scale of the human body. Often, the focus of landscape architecture is at the macro scale, the scale of the urban. That’s important, but in our studio we tend to focus on the more intimate scale, where inside and outside, and program and material conditions, converge with the human body.

TM: There is the stereotype of the New York architect as an interior architect – there are not a lot of greenfield sites – which leaves a lot of time for teaching, writing and exhibiting to feed back into the practice. Your work is broad ranging. How has this research been transformative to your practice?

JS: Throughout my career I have juggled teaching and practice, trying to make the two realms productively intersect: the academic issues that drive the work – like gender and more recently interface – have not been premeditated but are in part a product of circumstance. For example, working in a city like New York that does not offer many opportunities for small firms to design ground-up buildings encouraged me to think critically about the modest residential interiors that came my way. The personal and professional converged with Stud and [my essay] “Curtain Wars”: my frustrating experiences as a gay male architect designing residential interiors led me to consider how the professional rivalries between architects and interior designers are perpetuated by deep-seated cultural anxieties about decoration, gender and sexuality. More recently, the professional resistance I encountered when attempting to pursue landscape architecture collaborations led me to step back and again consider the way disciplinary divides are fuelled by cultural ideologies. Like interior decorating, gardening has also been devalued as a female pastime associated with domesticity. But complicating matters even further, in some contexts – like Hollywood cinema – landscape is gendered masculine. The American West is famously seen as a site for the performance of American masculinity – perhaps analogous to the outback as a place where Hugh Jackman performs his Australian version of virility.

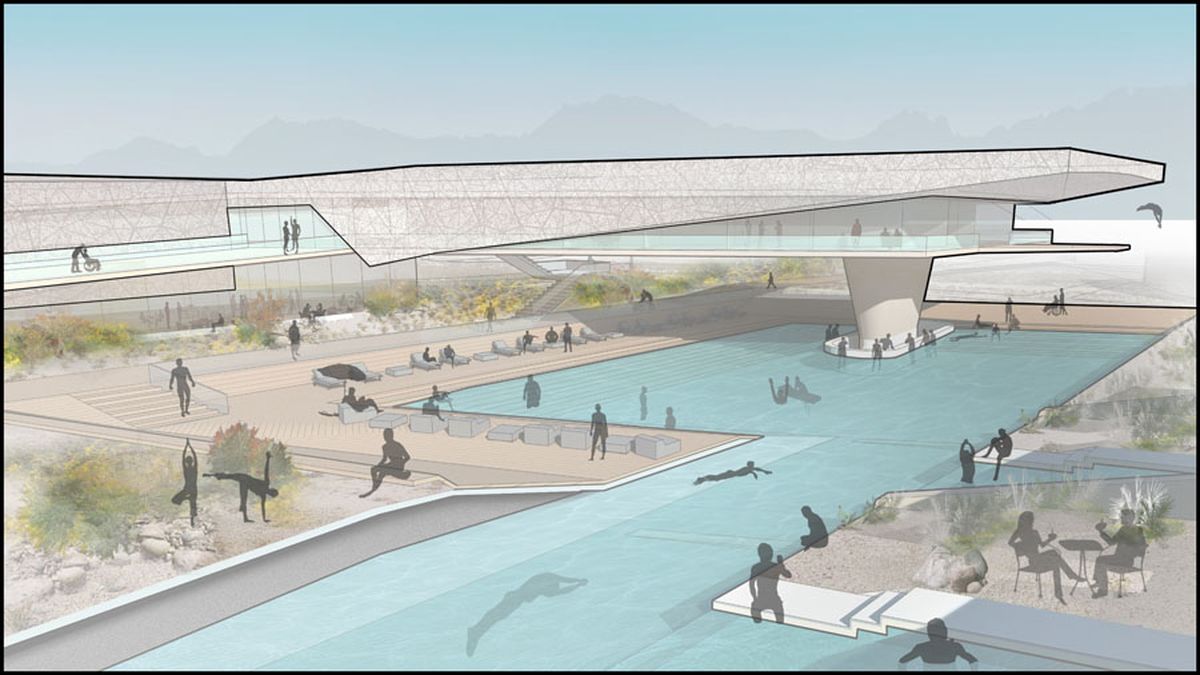

The masterplan of Boom by HWKN in Palm Springs, USA, demonstrates a variety of approaches to aged living.

TM: It seems pertinent to mention here that you are working on a site in the desert for a Gay Lesbian Bisexual Transgender (GLBT) retirement community called BOOM. This must certainly confuse the idea of the American West as being only a site of masculinity: now, instead, there is a rainbow of possibilities. BOOM involves architects including Jürgen Mayer, Lot-Ek, Diller Scofidio and Renfro among others. To come back to the diffusion of landscape and architecture as categories, how does this conversation play out in this project?

JS: In our project, landscape functions as an instrument to foster community interaction: the assisted facility, a place usually associated with death, is treated as a community centre that hosts a commons – a landscaped public space surrounded by senior residences. And instead of making a visual cut or segregation between assisted care and independent living, we have created a lap pool where people can swim from one place to another. You can swim into your neighbour’s place.

TM: It sounds like a Fire Island in the desert.

JS: While we crafted flexible housing types that sponsor a variety of lifestyles – families and roommates – it’s not another version of The Golden Girls or the The Pines [on Fire Island]. We are hoping that a queer perspective – a perspective that is not binary but representative of a broad diversity of identities – could generate alterative models of aging gracefully. This approach can also be extended to the landscape around us.