|

The library’s north and west facades.

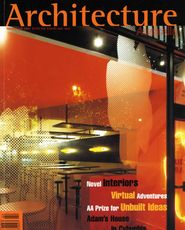

A sitting area facing north

Main study zone. |

Bates Smart’s Trinity College library at Melbourne University represents two important themes. They are the context of nearby historic buildings as references for its form and appearance, and the context of Trinity College within the overall campus. The first is the eternal architectural question of what should a building look like and the second is a more difficult urban design issue of how a building should fit into the city. The architects have alluded to two distinctive aspects of the existing college buildings. One is their face-stonework and the other is the cloister around the old quadrangle. The new library is built of split-face concrete blocks, referring to the stone as an economy demanded by contemporary circumstances. And a wide, two-storey verandah has been included (as access) on the library’s west side- detailed to mimic the heaviness of the Victorian cloister. Both strategies are explicit references to history which allow comfortable integration of the new with the old. However, the building form is less indebted to Trinity’s heritage than to a form common to many 19th century libraries. The dominant element is the vaulted roof (reflected in the first floor ceiling). The main room has been laid out-with high shelving around low-level bookshelves and central reading areas-to maximise the drama of this vault. The configuration is reminiscent of the grand reading rooms in Sydney and Melbourne’s State Libraries and is distinctly like that of the Bibliotheque Ste Genevieve in Paris. Whether intentional or not, these aspects of the design allude to the grandeur of old universities and the sense of privilege and protection associated with university colleges. The library’s heritage references are not literal because they have been reduced to minimalist versions of the originals. The blockwork is a modest stonework, the verandah is a simple, unadorned imitation of the existing cloister, and the interior vault is unexpressive. The old is reduced to new. Another aspect is how the library relates to the rest of the college and the university. In terms of the Trinity campus, it has been relegated to an outer corner, where it cannot contribute to the central quadrangle. This physical disconnection from the continuity of tradition weakens the architects’ contextural references. But an irony of that siting is that the library occupies a very dominant position on the university campus. Melbourne University has two distinct halves: the southern consists of teaching buildings and the northern is dominated by halls of residence and recreational facilities. In the north half, playing fields are bordered by an arc of colleges. The Trinity library is now a focus of that composition. It is located near the south-west corner of the playing fields, at a point which bridges the north and south campuses and serves as a gate for students walking from the colleges to the teaching halls. Inside the library, the architects have exploited this position by providing tall picture windows overlooking the orange athletic track and green hockey field. At this point of prominence, one would expect the library to flaunt its contemporary monumentality and historical references as an important new thread in the university’s fabric. Unfortunately, its weakest face is presented to the campus quadrangle. The east elevation is a bland, flat, blockwork wall with little revelation of the vaulted roof and none of the muscularity of the west verandah. There is no direct gate from the library to the path that leads to the rest of the campus. The building could have been a heraldic marker and gateway for students crossing the campus’ north-south border- but it has probably missed the opportunity to play a significant role in the university plan |

Credits

- Project

- Evan Burge Library & Education Centre, Trinity College, University of Melbourne

- Architect

- Bates Smart

Australia

- Project Team

- Tim Hurburgh, Mark O'Dwyer, David Grutzner, Cathy Stonier, Jim Tsoukatos, James Murray, Jan van Schaik, San Hurburgh

- Consultants

-

Builder

Salzer Constructions

Building surveyor The Hendry Group

Engineer Addicoat Hogarth

Landscape designer Dance Land Design

Project manager Kimpton Yuille

Quantity surveyor D.G. Jones

- Site Details

-

Location

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

- Client

-

Client name

Trinity College