The Translational Research Institute (TRI) at the Princess Alexandra Hospital (PAH), Dutton Park, is a compelling work of architecture by Wilson Architects and Donovan Hill. It is one of a number of new science research institutes built in Brisbane in recent years, mostly connected to major universities and hospitals. This building program, with its progressive development and design strategy testing, has been instrumental in attracting high-performing researchers and further research funding and has led to growing expectations for quality, architecturally designed workplaces within the close-knit science community.

The TRI is the result of a limited competition won in 2007 by Wilson Architects and Donovan Hill in association. It opened in late 2012, soon after the completion of their joint project for the Science and Engineering Centre at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT). Both practice histories include major science research institutes: Wilson Architects, for example, designed the Queensland Brain Institute at the University of Queensland (UQ) with John Wardle Architects in 2007; and Donovan Hill designed the Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation (IHBI) at QUT’s Kelvin Grove Campus in association with PDT Architects in 2006.

The purpose of the TRI, built within the grounds of PAH and less than fifty metres from the hospital itself, is to undertake translational “bench-to-bedside” research and to encourage collaboration and innovation in biomedical research fields such as cancer, diabetes, obesity and musculoskeletal disease. The TRI building accommodates four partner institutes: UQ’s Diamantina Institute, the Mater Medical Research Institute, the PAH Collaborative Centre for Health Research and Education (CCHRE) and elements of QUT’s IHBI. The institutes comprise a population of 950 (650 researchers plus 300 additional staff), gathered for the first time under one roof to undertake this significant collaborative research.

The competition brief for the TRI called for a second entry to the hospital grounds in the south-western corner off Kent Street, and this was incorporated in the architects’ proposal for a precinct-wide network of landscaped avenues. The brief also included incorporating the TRI’s companion operation, BioPharmaceuticals Australia (BPA). The selected site, in the far south-western corner of the PAH grounds, was for many years the territory of a helipad and Vision Australia’s two-storey brick building, which was to be either retained or demolished. A cleared site presented an opportunity to reconsider its land-use potential and at the competition stage the architects argued for the large, consolidated site to be conceived as dual sites for two separate buildings. This would allow for separate staging, reduced bulk and increased natural light and ventilation, benefiting both the buildings and the hospital grounds’ bleak environment. Subsequently the architects’ commission covered both the TRI and a new building for BPA, to be located on the adjacent sites. BPA has been constructed, simultaneously but in staggered phases, immediately to the south of TRI and is due to be completed later in 2013.

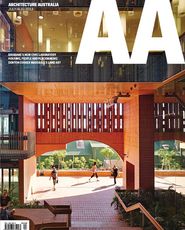

The eight-storey, forty-metre-tall TRI has been built on high ground within the hospital’s hillside campus and today stands as one of the tallest buildings in the neighbourhood. Although it has a smaller footprint than the hospital itself, the TRI’s height, protective carapace, colour and formal inflections make it visually prominent on the campus. And while subtly related to present-day surroundings through material and colour references, in height and scale the TRI stands apart in anticipation of future building within the constrained precinct.

The northern elevation reflects the surrounding buildings.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

Comprising many materials, the TRI building exterior presents a formal composition in reds and whites, largely free of material and structural coding. Recycled bricks from the demolished Vision Australia building set the red palette, augmented by custom bricks and pavers, terracotta tiles and copper sheeting. West-facing sunshade panels are freely composed to form a single white screen contrasting with, and fixed proud of, the red wall plane. Apart from a slice of green glazing – a nod to the BPA, trees and contrast – another bank of white sunshades fills out most of the eastern elevation. The sunshades introduce a long terracotta wall, signalling a formal entry off the stone-paved terrace. At the northern corner the wall joins other articulated and textured elements to form an earthbound terracotta base for the building. Apart from a few enigmatic openings, the TRI’s “blind” facades withhold the interior functions and character until well into the entry sequences. The austere presence of “blind” exteriors is mitigated here by tending to proportions, relative dimensions, colour, textures and composition, along with more than a few grace notes.

Visibility reinforces awareness of the presence of the whole TRI community.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

The TRI stacks four research levels, an administration level and a rooftop plant above the main entry level. The entry level incorporates reception, offices, an auditorium, a coffee shop and a generous gathering space, along with teaching spaces that can accommodate up to three hundred students in well-appointed laboratories, seminar spaces and a student lounge. Additional laboratory facilities, infrastructural facilities and the building’s loading dock are located on the lower ground level.

The primary function of this medical research institute is the laboratory. Various configurations of the brief’s generic units (laboratory for fifty staff comprising offices, laboratory spaces and laboratory support spaces) were tested by optimizing critical factors, including the number of units on one floor that would allow interaction through contiguous relations and the requirements of secure environments, back-to-back labs and write-up spaces.

Atrium-level reception area.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

Other objectives included facilitating interaction between researchers, providing outlook beyond the building and maximizing natural light through transparency and permeability across the deep plans. The optimal configuration of four units per floor, where each unit is provided with direct access to vertical services, resulted in four laboratory floors capped by a floor of meeting rooms – an arrangement which led to the adoption of the “U” plan and which in turn generated the grand space of the TRI’s six-storey atrium. And whether or not the atrium emerged as the result of rationalizing and optimizing laboratory layouts at the diagram stage, the “U” plan’s central space is a defended outdoor room – a recurring element in many Donovan Hill projects.

Architectural design operates with a myriad of competing elements – including instinct – to clarify concepts and arrive at a synthesis resolved for building. The TRI’s central atrium carries the symbolism of a singular room gathering all other rooms to it. It stirs recognition of the collective research endeavour. Visibility from upper and lower levels and across to partner labs reinforces awareness of the presence of the whole TRI community – its staff, visitors and the public – and of occasions such as conferences and celebrations.

A network of landscaped pathways through the hospital campus offered the TRI two significant addresses, ensuring easy circulation between the building and the campus and providing the essential conditions for the atrium to operate as a piazza. The east entry at the vehicle drop-off area brings visitors in at grade, past terracotta-red bollards and under a dropped bulkhead, along an interior passage. At this point there is a sudden release of space, with views into a vast volume that appears to be a great glass grotto, sparkling with the mirrored reflections of a thousand lights. A big opening with layers of staggered rosy glazing frames a slow shifting sky. At other times, entering the atrium via the north entry at dusk, the low sun appears to transform the interior, reducing contrasts as light from the west flattens out and seems to dissolve the glass.

The building’s “U” plan has allowed for a grand outdoor room.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

The entry level and the lower ground level are united in the terracotta base of the building. Clay elements are put to work to offer variety, texture, pattern and shape in floors and walls, in places that can articulate territory and enclosure, and in elements such as the fountain, the arch and the plinths for seating. This “outdoor room” anticipates and supports serendipitous interaction between researchers, hospital clinicians and others. Lifts and the central staircase connect the secure areas on upper levels with the reception and teaching spaces at atrium level. The large lecture theatre has stepped seating aligned with the terraced garden and with the contours of the adjacent terrain, opening onto the piazza with its garden, fountain, cafe and exhibition space.

The plush ambience of the atrium is both unexpected and vaguely familiar in its spatial grandeur and finishes associated with high-end hotels and offices. Rational planning of laboratory spaces, however, permitted the remaining budget to be distributed for quality materials, furnishings and fittings in restrained abundance throughout the building. A recent evaluation comparing the cost of the TRI with ten other institutes, benchmarked to 2010 when the TRI was tendered, indicates that the final building cost rate for the TRI will be very competitive.

The pronounced use of well-known motifs by other architects is a surprise in this work and tends towards a postmodern interest in architectural quotation that will intrigue students. First among the TRI’s many architectural gifts, however, is the atrium – a piazza that opens freely onto common ground outside, offering respite from the relative chaos and clinical environment of the hospital. Open day and night to patients, staff and visitors alike, this defended outdoor room presents a memorable sheltered place with water, trees, air, sunlight and views of the sky.

Credits

- Project

- Translational Research Institute

- Architect

- Wilson Architects

Spring Hill, Brisbane, Qld, Australia

- Project Team

- Timothy Hill, John Thong, Michael Hartwich, Damian Eckersley, Hamilton Wilson, Brian Donovan, Fuller November, Simon Swain, Sophie Atherton, Domenic Mesiti, Melissa Dever, Lucas Leo, Sarah Russell, Chris Hing Fay, Sarah Neale, Tim Jukes, Simon Depczynski, Ash Every, Wei Jien, Lauren Wellington, David Evans, Charlotte Guymer, Robert Myszkowski, Alisha Renton, Jasper Brown, Michael Herse, Roland Fretwell, Greg Lamb, Beth Wilson, John Harrison, Kamil Kuciak, Ilka Salisbury, Paul Jones, Phil Hindmarsh, Hyun Kim, Martin Arroyo, Daniel Tsang, Michael Bailey, Sarah Woodhouse, Andrew D'Occhio, Tomoyuki Takada, Peter Harding, Nick Lorenz, Dana Hutchinson, Phillip Lukin, Michael Hogg, Shaun Purcell, Rebecca Lee, Jessica Riske, Sally Tyrell, Brent Hardcastle, David McRae, Michael Ford, Briohny McKauge, Maddie Zahos, Santanu Starick, Neil Wilson, Kae Martin, Lisa Matray

- Architect

- Donovan Hill

Brisbane, Qld, Australia

- Consultants

-

Acoustic engineer

Ask Acoustics & Air Quality

Builder Watpac

Building certifier Certis Group

Civil engineer Opus International Brisbane

Cost planner Davis Langdon

Electrical engineer Aurecon Brisbane

Environmental consultant AECOM

Fire engineer Exova Warringtonfire Brisbane

Heritage ERM

Hydraulic engineer Opus International Brisbane

Landscape architect Wilson Architects, Donovan Hill

Mechanical engineer Multitech Solutions, Hawkins Jenkins Ross

Process engineer TBH

Specs writer Kim Humphreys

Structure and facade engineering Aurecon Brisbane

Surveyor Certis Group, Eric Martin

Vertical transport engineer Cundall Australia

- Site Details

-

Location

Dutton Park,

Brisbane,

Qld,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Category

Health,

Interiors,

Public / cultural

Type Clinics

Source

Project

Published online: 6 Sep 2013

Words:

Brit Andresen

Images:

Christopher Frederick Jones

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2013