|

| ||||

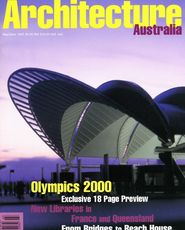

top Detail of north-west (entrance) elevation, showing perforated metal sunscreens and great verandah aligned along the main campus axis. above North-west elevation as seen from the campus axis.

More photos can be found | Photography John Gollings Review John Hockings The site of the new Sunshine Coast University is a low, flat, featureless plain, part of the hinterland just to the south of Buderim Mountain. Once a canefield, it lies immediately to the west of a particularly sensitive stretch of national park forest. The ground slopes gently to the east but the feel is of a broad grass paddock compressed under a huge sky. I remember standing in this paddock a couple of years ago. Nothing caught my eye. There was no view to settle on, no natural way to face, no place to pause or sit. Even the horizon is reduced by the huge empty space to a thin even line; part forest, part new housing estate, the colours dulled and blurred by the intense light. Here, Canberra-based Mitchell/Giurgola & Thorp (MGT) and Brisbane architect Geoffrey Pie have attempted to carve out a place for a new university. In their masterplan, they reacted against the expansiveness of the site to adopt a traditional, urban model with conscious echoes of Virginia. The scheme focuses the whole campus towards a formal avenue aligned north-west/south-east to acknowledge the only discernible site features: the sun and the slight slope. Rather than looking outwards to the surrounding landscape, the buildings along the avenue thus face in and onto the ‘urban street’ and towards each other. As if to reinforce this approach, the non-street sides of the buildings along the axis look out to extensive carparks. The intention is an urban one: the campus as compact town replete with traditional urban elements including lanes, courtyards and formal buildings surrounded by a separate ‘rural’ realm of playing fields and carparks. Town and country only meet at the lower end of the avenue, where a lake collects and cleans surface water run-off before it is allowed into the national park. It is clear that the character of the campus is to be derived mainly from the character of its buildings and its internal landscape, and not to any great extent from the view out to the broader landscape. Yet the first buildings and landscape works have not responded to this challenge in a truly convincing way. Considering the axial basis of the masterplan, it is surprising that the avenue is intentionally interrrupted one third along its length by the library: posited as the symbolic and physical core of the campus. One suspects it was imagined as having something of the monumental formalism of Jefferson’s Pantheon. However, the library architects-Lawrence Nield from Sydney and John Mainwaring from Noosa-have successfully revised that classical American approach. Here is a piece of architecture with an idea, an identity and an intellectual content which reflect both the relaxed open-air character of the north coast and the aspirations of a new centre of learning and research. It is a sophisticated building at many levels, and is strong enough to not just conform with the masterplan but to redirect and redefine its intentions. In the masterplan, the library was to be a monumental blockage to the axial avenue. But the architects argued, with scale models, for a re-evaluation of this idea. Although the site was fixed, they felt it preferable to allow the avenue to flow ‘through’ the library- along a great open verandah-so the building can be read as axially transparent. The earlier campus pavilions, though evidently intended to respond to climate, present opaque facades to the avenue, close off the surrounding landscape and, by their heaviness, appear unresponsive to breeze, light and movement. The shift to a concept which emphasises lightness and transparency-as a means of arranging the whole environment and as an idea for individual pieces of architecture and landscape within it-seems wholly more appropriate for the future of the campus. Both the formal avenue and the centrally located library of the masterplan can be seen as answering some perceived need on the part of the planning group to place the new campus within the tradition of the great universities, and to lend the campus an air of dignity and authority befitting a place of knowledge and learning. Bond University attempted to buy its tradition in the same way, and Yale long before that, as if through the construction of hallowed forms (preferably in sandstone), hallowed authority and knowledge would follow. How much more convincing is the approach of Nield and Mainwaring. Ideas of light, liberty and learning are not acquired through the appliqué of solemn and nostalgic forms. Instead, the building expresses, through the ideas it embodies and the manner of its construction, a considered intellectual and poetic attitude to program, fabric and site which can then be taken to mark, by example, the authenticity and the creativity of the whole university. In these achievements alone, the building has done the campus an immense service through providing an inspirational vision for its ongoing development. In a short article, it is important to make that clear, though it leaves little space to discuss the considerable merits of the building as a library and as an architectural piece within its immediate surroundings. It is clear from discussions with both architects that certain strong concepts took the idea of the building far beyond a simple diagram of program requirements. Of great importance was the idea that the library should project itself outwards, making connections with the university and the new community which is progressively encroaching on this site from the horizon. While many libraries present themselves as fortified and internalised boxes, this building reveals itself and its contents to the surrounding world through a variety of peeled away edges which invite occupation and curiosity. From the great slatted entry porch, with its long “university seat” providing views out to the surrounding landscape, to the skilfully shaded transparent external walls and the many undercrofts and reading nooks, the building insists upon active connection with life around it. It is remarkable how much life there is around the edges of this building, and how many people are attracted to its terraces, half-landings and undercrofts as places to meet and chat and, to the surprise of even the architects, use as venues for cultural and social events not necessarily connected with the library. This is the mark of a true public building: to foster a public life within its own orbit. Inside, two notable ideas have driven the arrangement. One is the awareness that the users of the library tend not to be the large classes found elsewhere on campus, but rather individuals and small groups. Sectional subdivisions and planar compositions have been carefully worked to create spaces at a scale conducive to undistracted individual study. The architects also used the analogy of the woolstore to inform the cross-section. The old Sydney and Brisbane woolstores gave over their lower levels to large-scale warehousing, while their top floors were great skylit spaces devoted to meticulous examination of the fibre. A similar schema operates here, with the lower floors housing books and equipment in a concentrated layout, while the top floor, for readers, is open and brightly daylit. This imaginative building testifies to the fertile association of Lawrence Nield and John Mainwaring, along with talented members of their respective offices. It also rewards the careful briefing of the university’s building committee and its commitment to bring together local and national architects to create a new campus which could embody the best of the human intellect and spirit and a sense of belonging to the region it supports. John Hockings is a senior lecturer of the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Queensland. Sunshine Coast University Library, Maroochydore |