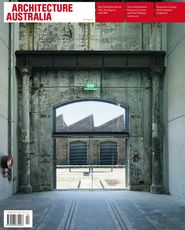

The Faculty of Law building proffers differing facades for each elevation.

Located where a car park and beer garden once stood, the new building maintains the “University Mall” and the line of existing poplar and fig trees.

Bold, graphic elements lend visual interest to the ground-level agora.

“The Tree of Knowledge”, a series of trapezoidal timber panels, spirals up the primary vertical circulation space.

A visual connection to the outside is maintained in most spaces.

Customdesigned furniture punctuates the articulated hallways.

The interior colour palette has been likened to the ripe figs found on neighbouring trees.

Condensed secondary circulation spaces encourage informal contact between staff and students.

Maximum natural light penetration is afforded via a substantial lightwell in the vertical circulation space.

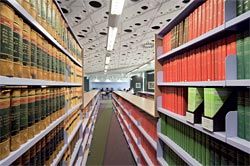

Both the perimeter and the interior of the faculty library feature extensive glazing.

Looking through the bookshelves in the library.

When he presented the UNSW Faculty of Law at the School of Architecture at UTS early last year, while the building was still under construction, Corbett Lyon was accused by a member of the audience of felling Sydney’s best fi g trees and destroying a prime urban space to make way for “his” building. Site selection and axe wielding were not, in fact, Corbett’s responsibilities.

A former car park and beer garden, the site is part of the rejuvenation of the north end of the mall as endorsed by the UNSW Kensington Campus 2020 Master Plan, of which our irate audience member had been an author. At a cost of over $50 million, it is implausible to pitch this competition-winning scheme as a wilful imposition on an unsophisticated or careless client.

The charge could only be understood as distaste for the architectural outcome. This distaste has been collectively reinforced by the jury for the NSW chapter of the 2007 RAIA architecture awards, who have pointedly failed to shortlist the building. In what ways, then, does Lyons’ design depart from the master plan and how could this occur, given that each was prepared around the same time for the same client?

Central to the master plan is the preservation of the “University Mall” and the line of poplar and fig trees that frames it. This is unbroken by the new building – indeed, placement of the main entry between two mature fi g trees emphasizes the relationship between landscape and building. In relation to other objectives in the master plan, the law building complements the alignments, scale and materiality of neighbours; it is a slab building of four stories as specified for that location; it is permeable and provides through-building links at the ground floor; and it maximizes natural light penetration. Additionally, Lyons’ design has “a distinct architectural character” as recommended for new buildings. It is due to this last qualifier that curious and diverting complaints about lost trees arise.

“Distinct” means “of marked difference”. Applied to the management of the accretive design of a campus as a desirable quality, distinctiveness is likely to work against consistency of architectural expression or the “even temper” that Philip Drew, in this journal in 2004, admired in the university’s new architecture. If it was the indistinct, polite distinction of MGT’s Scientia that the authors of the master plan had in mind, this was not what the Faculty of Law sought – or got – in their fi rst purpose-built facility since opening in 1971.

Comprising the Schools of Law and Taxation (Atax) and numerous research and community centres, these were dispersed in temporary accommodation. The faculty has always maintained a strong focus on social justice and change, exemplified by the provision of free legal advice to the community through the Kingsford Legal Centre and contributions to public debate through the Gilbert and Tobin Centre of Public Law. Larissa Behrendt, Peter Garrett and Pat O’Shane are among their alumni.

In keeping with their philosophy, the conventional large lecture format is replaced by seminar-style classes based on interactive dialogue between students and lecturers. Accordingly, there are 13 small classrooms in the new building where most of the teaching takes place and a condensed circulation that supports informal social contacts between colleagues and between staff and students. While formal tactics familiar from the Lyons oeuvre – the oblique line and folded plane, repeated graphic patterns and stripes, and an abstraction of structure and material – are repeated here, these have been tailored for the specific programme and accurately mirror the faculty’s strong identity as a progressive and engaged institution.

The Dean of Law, Professor David Dixon, considers the building and the ambitions of the faculty to be in concert. Promotional literature is enthusiastic about the new building, rightly proclaiming its “distinctive facade” to be “hard to miss”. As with earlier projects by the practice – the botany building for the University of Melbourne and Building C for the University of Swinburne’s Lilydale campus – the building’s four main facades are highly individuated and complex in their layering, folding, screening and peeling. While some of the facade treatment responds to solar orientation and access, there is elaboration for visual pleasure in its own right.

Circulation through the 12,000 square metres of floor space is legible and the programmatic organization considered, yet the spatial experience is convoluted and complex. From most spaces – even the 350-seat auditorium – you can see out to the campus or to other spaces within the building. Connections between spaces are multiplied visually and physically.

From any point outside the building to an individual offi ce, there are always numerous alternative paths available. The corridors of academic offices do not subdivide into linear wings, but circle back upon themselves and around courtyards cut into the top two floors.

Embedded in the main vertical circulation space is a spiralling pattern of trapezoidal timber panels that the architects refer to as “the tree of knowledge”. Lyons’ tree is to the tree-columns marching through MGT’s Scientia at the other end of the mall what figs are to pines. The fig is tangled, fecund and produces suckers, whereas the scent and tidy form of the pine lend themselves easily to car fresheners and idealization. The deep purples and greens that dominate the interior are also redolent of ripe figs. And at the risk of stretching too far the vegetal allusions, what come to mind are the evocative distinctions Deleuze and Guattari make in A Thousand Plateaus between the arborescent and the rhizomatic.

For them, rhizomatic organizations and ways of thinking are non-hierarchical and multiple like grasses.

The rhizomatic has its spatial correlative in “smooth” space – space that is open to creative movement in any direction. Smooth spaces are composed of trajectories rather than destinations and are filled by events rather than things. The arborescent, by contrast, subdivides, like a tree, from a larger category into smaller and smaller categories – much like the organization of knowledge into disciplines and departments in universities. Arborescent thinking has its spatial correlative in striated spaces, which are ordered, structured, gridded and sedentary.

It is interesting to consider the organization of the university, idealized in the master plan, as arborescent, with its call for precincts and places hierarchically organized. At the level of the faculty, the approach that has been given form in Lyons’ building tends to the rhizomatic. Deleuze and Guattari do not propose the rhizomatic and the arbolic as opposites, nor do they value one over the other. They suggest that these are tendencies and useful ways of thinking, not fixed categories or truths. Consequently, some of these terms have found their way from the desks of academics to university managers and management more broadly.

In undertaking significant work for several universities, Lyons is well versed in current debates about the physical and corporate organization of the university in relation to strategic goals and activities. Universities are seeking more flexible, responsive, horizontal structures better suited to the challenges of global culture and business, yet also wishing to preserve their role as loci of critical thinking, self-knowledge, humanism and inherited traditions. Lyons’ new building at UNSW gives cogent architectural expression to one faculty’s desire to be relevant, progressive and visible, while locating it as a node within an underlying order that operates with different ambitions. Moving back and forth between the singular urban gesture of the mall and the highly condensed spaces of the law building, one senses the complexity of the university’s divergent undertakings and the productive tensions between them. It is a great pity that some local architects have dismissed the building on the grounds that its aesthetic departs from the decorous modernist box without making the effort to understand how its formal appearance and spatial organization respond to the client and their challenging needs, or to recognize that there are many forms good architecture can take.

A computer laboratory within the library space.

The 350-seat auditorium.

Images: John Gollings

FACULTY OF LAW, UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES, KENSINGTON

Architect

Lyons.

Structural consultant

Bonacci Group.

Mechanical and electrical consultant, fire and fire service engineer

Bassett Kutter Collins.

Acoustic consultant

Marshall Day Acoustics.

Hydraulic consultant

Alexander and Associates.

Facade engineer

Connell Mott McDonald.

Quantity surveyor

consultant Slattery Australia.

construction Rider Hunt.

Building surveyor

Gardner Group.

Project manager

McLachlan Lister.

Construction manager

Bovis Lend Lease.

Client

University of New South Wales, Faculty of Law.

Credits

- Project

- UNSW Law

- Architect

- Lyons Architecture

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Acoustic consultant

Marshall Day Acoustics

Building surveyor Gardner Group

Construction manager Lendlease

ESD, mechanical, electrical and fire Bassett Kutter Collins

Facade engineer Connell Mott MacDonald

Hydraulic consultant Alexander & Associates

Project manager McLachlan Lister

Quantity surveyor Slattery Australia, Rider Hunt

Structural consultant Bonacci Group Sydney

- Site Details

-

Location

Kensington,

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Education

- Client

-

Client name

University of New South Wales, Faculty of Law

Website law.unsw.edu.au

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Jul 2007

Words:

Sandra Kaji-O'Grady

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2007