From house to housing

“If we want to raise the quality of living … then the most effective way of all is to improve the quality of the house … The physical state of the house reflects the economic state of the nation, directly and sensitively … However … its ability to uplift or depress: its design – has practically no vested interests pushing from behind …”1

Robin Boyd emphasized the “house,” whereas today we might talk about “urban housing” and its specific architectural form, the apartment building. The need to share urban, cultural and transport resources is reinforcing compact collective living. Apartment buildings are becoming the urban signifier of the societal change that is reshaping the ways we live.

Along with the shift from suburban to urban densities, Australia has traded the innocent domesticity implicit in Boyd’s “living” for the more glib construct of “lifestyle.” Long understood to be the provision of necessary accommodation, today housing is seen through the narrow lens of “development” self-interest. As a fast track to profit via unearned income and asset inflation, housing is frequently conceived first as a market, with societal need a distant second.

The public sector involvement that has historically diversified housing choices has been in sustained decline for decades. The pervasive commodification of housing has inflicted a paralysing timidity on its architecture: the typology, planning, expression and diversity of mass housing has stagnated while ignoring our best urban housing traditions.

This commodification, as expressed in the lack of architectural quality and character in the majority of our collective housing, betrays a longstanding and deeply felt cultural resistance to urban forms of living.

Despite our perennial affluence, Australian cities are not home to well-designed mass housing. Apart from singular exceptions that tend to miscategorize “architecture” as an indulgence reserved for the wealthy, most housing has scant architectural input. Furthermore, the architectural profession has shown limited engagement with crucial housing challenges.

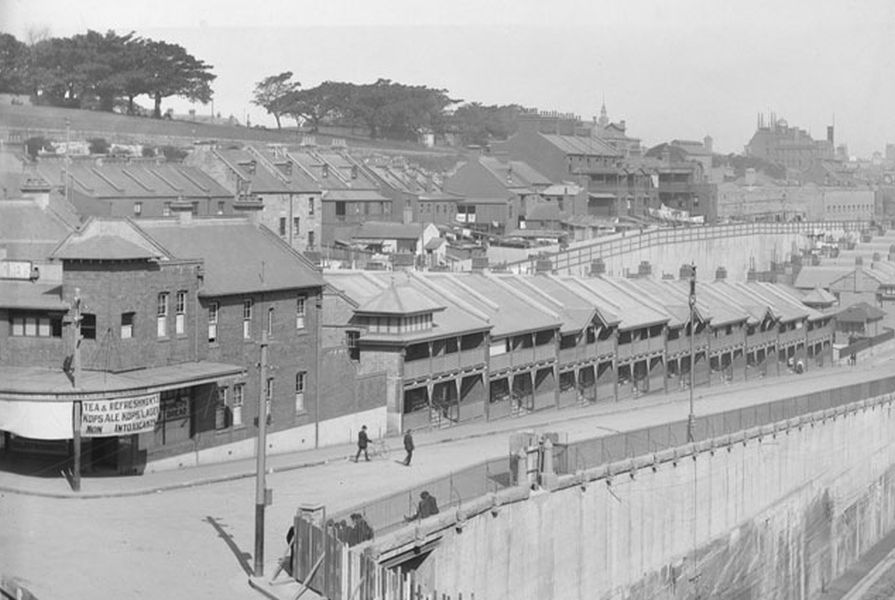

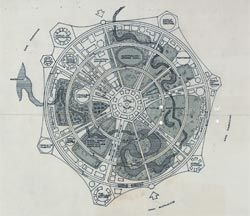

Robin Boyd’s sketch plan for the 1972 World Exposition, including a model suburb that would be “an idealistic projection of Australia’s suburban way of life”.

Image: Grounds Romberg & Boyd Collection (Manuscript Section) Box 118/1b. State Library of Victoria

Valuing housing

Housing as real estate has dramatically shifted the way we define housing’s worth. The value of apartments has become widely understood by estate agents’ reductive formula: How many bedrooms? How many bathrooms? How many car spaces? What brand of European kitchen appliances? Add to this their insistence on airconditioning, regardless of environmental design.

In Living in Australia, Boyd explored the character of housing through an examination of its surface, space, structure and spirit. Such qualitative and sophisticated readings of architecture’s contribution to “living” are absent from today’s public discourse about and understanding of mass housing.

The marketing of the architecture of mass housing is stripped of any sense of the qualitative lived experience of space. Generic interior perspectives abound, where the surface gloss of furniture and the view are given more weight than the architecture. Exterior perspectives monumentalize and isolate new development – exploiting each building’s independence and novelty rather than its connectedness to place and society. Boyd’s detested “featurism” has either been writ large in mega buildings or bypassed by “featurelessness” across our cities: the brazen and the bland.

The descriptions of new housing invariably list the riches that a particular new development will allow purchasers to leverage from the city – the proximity to a diverse and rich cultural life, parks, open spaces, shopping, dining and views. Where is the quid pro quo? The question of what contribution these buildings make to the structure, quality and character of the city remains unanswered.

Scarcity and inequity

A diminishing supply of housing and the vastly reduced investment in public housing has seen housing scarcity and equity become growing problems in Australia. A policy vacuum allied to crude financing and taxation practices has caused a housing affordability crisis.

Our taxation system rewards existing wealth. The tax-free status of the family home combined with generous negative gearing and capital gain regimes are accelerating inequity, wedding the nation and its housing stock to the thrill of speculation rather than long-term investment in one of society’s most fundamental needs.

The financial sector exacerbates this situation by imposing ill-conceived limitations on urban housing. The financial dictates that impose arbitrary fifty-square-metre minimum apartment sizes, maximize pre-sale requirements, and limit forms of commissioning and title affect both housing providers and users. The combination of these blunt rules stymies genuine choice, dents affordability and delivers mediocrity.

Politics and planning

Planning controls often enforce suburban ideals and forms by stealth, stifling the emergence of a positive urbanity. Ziggurat height and setback controls, the requirement for buildings to be “contextual” in areas where change is desirable, and the blanket zoning of variously termed “heritage conservation areas” or “neighbourhood residential zones” are all symptomatic of a culture predicated on the belief that any change should be feared implicitly.

Today, the initial planning application for even a modestly sized apartment building typically requires input from perhaps a dozen consultants. Appeals to court and independent planning tribunals are not uncommon. Canny applicants know better than to submit housing applications in the lead-up to local government elections, when their proposals risk becoming fodder for anti-development grandstanding – a trivial substitute for necessary and urgent policy debates about housing equity and change in our cities.

The ever-increasing costs associated with the complexities of compliance and regulation are either being deducted from the construction budget or passed on to the purchaser – impacting the quality of our building stock or affordability. While economy is a noble aim in urban housing, the limited investment in the material quality and character of urban housing undermines its role in city making.

Standards and legislation

The portents of bad housing continue to reappear, irrespective of budget or market pretensions: the deep plan, internal rooms, low ceilings, inadequate light and air, miserable outlook, mean common spaces, residual open spaces, token landscape, substandard construction, perfunctory character and a deadening presence on the street. Enforceable minimum amenity standards are as essential as ever, which makes legislation to improve architectural quality in apartment building design all the more imperative.

New South Wales’s State Environment Planning Policy no. 65 – Design Quality of Residential Flat Development (SEPP 65), introduced in 2002, was a noble attempt to require better practice through legislation. However, one of its primary mechanisms, the design review panel, has only “advisory” status and patchy coverage.

Design quality must have real legislative weight and follow-through. It is not sufficient for architectural quality to be assessed only at the planning stage – it remains at the mercy of the market following design approval, as is evident in the marginalized role that many architects find themselves serving during documentation and construction. Independent review during the construction process by a design review panel would do much to ensure the carry-through of the design intent and improve the quality of the built environment.

The architecture of urban housing

For centuries, architects have generated model projects that become generalized as housing types: the Adam brothers’ Adelphi Terrace in London; Michiel Brinkman’s Spangen Quarter in Rotterdam, stacked units with perhaps the first “street in the sky”; Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation, the monumental slab in Marseilles that presaged the deep floor plan; or Tadao Ando’s inhabited, terraced hillsides in Rokko.

There are numerous parties looking after housing quantities, but it is architects who have to imbue these quantities with qualities – exploring social and spatial organization, providing generous access to light and air, calibrating privacy and outlook, crafting the project economically, providing release to and definition of garden spaces, forming the block and defining public space.

When allied with street life, apartment buildings become the city’s connective fabric – supporting an engaged community life of social facilities, shopping and exchange, and multiple transport options.

Le Corbusier’s Unite d’Habitation, Berlin (1947-1952).

Image: Ikkoskinen on Flickr

Aldo van Eyck considered that “Architecture needs no more, nor should it ever do less, than assist homecoming.”2 Such a proposition can inform both typology and experience, describing the passage from the public street through the common areas to the feeling of welcome upon opening the front door. How does the architectural model fit and adapt to the confined dimensions of the lot, intelligently occupying its site? What is the spatial sequence, the everyday promenade architecturale, the casual generosity of its social spaces? Within the unit, what promotes homecoming? Is it the relationship of rooms, the movement of sunlight, the flexible operation of modulated apertures, the opening to the terrace or balcony? Beyond the trifecta of view, finish and size, what is the spatial conception of the unit, its distinctive arrangement and sectional play? How are the selected unit types open to appropriation by successive inhabitants?

What of the architecture’s public face – the relationship of the building to the street? Questions of its scale and the relative urbanity of its street presence need to find a commensurate architectural register. What type of city does it anticipate? Whether urban or suburban, how does the site plan mould the building to form positive external spaces that can be appropriately and delightfully landscaped?

Beyond the seemingly ubiquitous base palette of brick, aluminium louvres/screens/panels, tinted glazing and painted precast concrete, what durable and noble materials are available? These buildings will likely last a century, at least; how robust and flexible will they be?

Architects have long championed well-designed housing for all. This was one of Modernism’s most deeply held tenets. In closing Living in Australia, Boyd proclaimed, “architecture in the end is a fundamental requirement of living.” Boyd’s challenge should embolden us to redress the marginalized contributions of our profession, the quality of our dwellings and the state of Australian cities.

Projects that reflect an informed architectural agenda can be pursued in the current housing climate. But it is not until projects like these are the rule, rather than the exception, that housing’s role in the making of the city can be fully prosecuted.

1. Robin Boyd, Living in Australia (Melbourne: Thames and Hudson, 2013), 22.

2. Herman Hertzberger, Addie van Roijen-Wortmann and Francis Strauven (eds), Aldo van Eyck: Hubertus House/Hubertushuis (Amsterdam: Stichting Wonen/Van Loghum Slaterus, 1982), 65.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 26 Aug 2014

Words:

Laura Harding,

Philip Thalis

Images:

State Records Authority of New South Wales

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2014