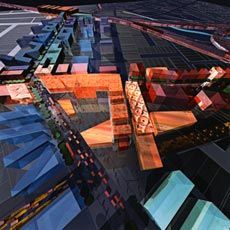

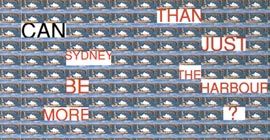

Images from SydneyCentral, the winning design in the Parramatta Road Urban Design Competition, by Choi Ropiha, McGregor + Partners, Stanisic Associates Architects, VIM Design, The Revolution, King & Campbell, Hill PDA and TTM Consulting.

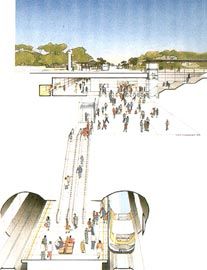

Concept design by Hassell for new and upgraded stations for the proposed Parramatta to Chatswood Rail Link. Hassell is now undertaking the detailed design for five underground stations between Epping and the proposed UTS station at Ku-ring-gai.

NSW Government Architect Chris Johnson arrived in the west of Sydney in 1995 at Homebush Bay, already wondering how settlement there ought to be improved. What mattered to him was to render settlement west of Sydney authentically. Is the west part of Sydney? Is the west a single homogeneous tract? Are architects equipped to work where investment is wanting?

But if you think that the musings of architects alone will cause real improvement west of Sydney, think again. The works recently mooted by the NSW government are major infrastructure projects and their impact has the potential to be dramatic.

An understanding of what drives the western hinterland of Sydney has eluded many architects bent on showcase architecture – a sort of decorative modernism, which has usually meant pursuing some strain of minimalism, beautifully photographed. It is unusual for these single buildings to cause any lasting change beyond their own boundaries. So, if architects are indeed so blinded, and at the mercy of their industry and its commerce, from where will major structural improvement to the west emerge?

The NSW government has in train an initiative to revitalise Parramatta, a Parramatta to Chatswood Rail Link, the $1 billion Western Sydney Orbital, the fanciful Very Fast Train between Canberra and Sydney, the Parramatta Road Design Competition, and the probable relocation of some 50,000 square metres of government departments to Parramatta.

The thrust is two-fold. The first is to redress ways of seeing Sydney’s western hinterland. The argument forcibly put by Penrith Councillor Clair O’Neill, of the Western Sydney Regional Organisation of Councils, is that the western suburbs belong to the regions still further west – they look toward the Blue Mountains, not east to the city and Bondi.

“Don’t show me pictures of Venice or Rome or Berlin because none of these places have the characteristics that can allow architecture to be effectively reproduced,” O’Neill said in September when she was joined by Chris Johnson, Paul Keating, and RAIA NSW President Richard Francis-Jones in a debate about whether architects can contribute to the development of the west.

O’Neill describes a region that is an urban, rural and natural landscape, not merely a suburban one. Most of it has never been affected by the hand of an architect.

And on the occasions when architects have been active, they have tended toward the one-off statement building. Outcomes have been both positive and negative, but, in the main, architects have had marginal effect.

The initiatives of the NSW state government provide an opportunity for architects to now have a big impact. There is an emerging acceptance that the west has its own local identity distinct from Sydney, and that the infrastructure and housing markets there have long been removed from the domain of architects.

The second part of the government’s strategy is the mooted infrastructure projects themselves. These are all publicly funded in part or in full. In a project like the Hassell-designed Parramatta to Chatswood rail line, flamboyance can be read as a gesture of hope. Indeed, the theme of the Hassell scheme is “connecting to the future”.

“Can Sydney be more than just the harbour?” This is the headline of the winning SydneyCentral design for the Parramatta Road Design Competition. The design embraces Parramatta Road’s prevailing uses – showrooms, traffic, offices and so on. But it rearranges these into hybrid buildings: multiple uses and conflated activities replace the existing separated, singular and exclusive buildings. The designers use architecture and infrastructure to change the way we perceive the centre of metropolitan Sydney westward from the city proper to the linear Parramatta Road.

At the other end of the market, Johnson also uses prevailing building types. He wants suppliers of housing to use architects in the production of project homes and apartment buildings. He sees no reason why architects, alone in the building industry, should produce works that are unique and incapable of repetition. The very tools of an architect’s trade are modular, repetitive and mass-produced. Some architects might deny it, but the odds are that their very mind is modular, repetitive and mass-produced too.

They just refuse to let their pretence to artistry be undermined.

Of course the contribution of architects can have the effect of pushing up property values. Should this put buildings beyond the reach of the very consumers needing to be served, then the exercise would be wasted.

Johnson approaches this cycle innovatively. He knows that real, lasting change will be created by yoking the building industry to the architectural industry, not by each acting in parallel, linear separation. He wants to put the systemisation of architecture and the cyclic interest in project homes together with the evidence that home owners are increasingly demanding a say in the design of their homes.

Borrowing from internet shopping and from architectural systemisation, Johnson has produced a “mix and match” shopping cart for project home and apartment delivery. The party yet to be convinced of the value of this idea is the building industry itself. Why change to another model when, in their view, things are working fine? But Johnson’s project home need not dumbdown a house and thereby spook architects; nor need it push up prices and threaten the providers.

This is an exciting and game direction in which to lead settlement patterns. It is also an inflection of things attempted by others in the past. It is reminiscent of John Entenza’s efforts to involve Eames and Neutra in California after World War II, and of Pettit & Sevitt in Australia. This strategy accepts that consumers have the intelligence to determine their environment, and that increasingly they will demand it. It is also about ways of seeing. Whether working on housing or transport infrastructure, the architect who moves west is enjoined to design for urban, rural and/or natural areas. This kind of environment has received little architectural attention, and scant press, although it is where the majority of Australians live.

In NSW, the opportunity created by the state government presents a challenge to builders and architects to shift their working habits. Indeed, the professional habits in which architects take comfort – confident in the safety of their repetition – will be of little use when working in cities out west. If this burst of government activity can successfully involve architects, it will doubtless equip those architects with a resourcefulness to work anywhere.

Christopher Procter is an architect and a principal of Project