A bold new masterplan for the Perth Waterfront has got the go-ahead for further development. We present the LandCorp proposal, designed by Ashton Raggatt McDougall with Richard Weller, Roberts Day Group, and Hocking Planning and Architecture, along with five responses to it.

Designers’ statements

The idea of the circle as the key organizing idea for the site.

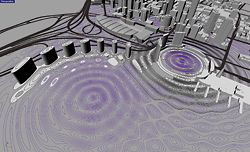

Interference pattern generated through the intersection of ripples from two source points.

The two circles and the site.

The circles and the interference pattern “weld the city and the water”.

Aerial view showing proposal.

Looking west over the River Circle, a 500-metre-round promenade.

Aerial view over Mounts Bay, looking north-east to the Circle.

Looking up the William Street axis. The public building is in the foreground.

Aerial view looking north-west over the Supreme Court Gardens.

Some facts: we are living in the twenty-first century but the Perth CBD is encrusted somewhere in the mid twentieth. The Perth metro area has three times as much open space as it does built space and almost all that built space is suburban. Perth has over 140 kilometres of river edge and all of it is under-used green space. There is no urbanity on the Swan River. Of the 140 kilometres of riverfront, the new Perth Waterfront will develop only one kilometre. Additionally, bear in mind that the population of Perth is predicted to double by 2050, reaching three million. Many more people will live and work in the city and people generally will demand high-quality designed environments and services. For these reasons this project is a watershed.

Many remain suspicious, however, that this is just another “artist’s impression”, the latest layer to be added to the geological strata of drawings that have attempted to overcome the no-man’s-land that traffic engineers created between this city and its river. But things are a bit different this time. The city is particularly affluent, the politicians are committed and the public, like never before, wants urbanity. And maybe, at a fundamental level, the design is right.

Why? Firstly, it focuses energy in a good location, i.e., it is grafted onto a new train station and builds the city out toward the river between William and Barrack Streets, Perth’s main north–south axes. Secondly, as a priority, the urban design uses built form to make high-quality public space and conjoins the river and the city by quite literally enfolding the river into the city. There are two major public places framed by this urbanism: the Esplanade Square and the River Circle. The square captures and enhances the bustle of the big city (Perth’s Fed Square to be), whereas the River Circle, a 500-metre-round promenade, is more about framing the beauty of the river. The circle and the square present Perth with grand civic spaces, the likes of which it has never had. Finally, I think there is the right amount of development – neither too much nor too little, as has bedevilled other schemes.

It wasn’t easy to find the key to this site. It’s a deceptive tabula rasa – one that invites megalomania but has only ever accepted the twee. While it seems archaic to have called upon the classical figure of the circle to do yet more work in the history of (landscape) urbanism, it alone seemed capable of holding this project in place. Let’s hope it not only endures as an anchor, but also becomes a source from which to raise some daring buildings.

Richard Weller is professor of landscape architecture at the University of Western Australia and a member of the design team for the LandCorp Perth Waterfront masterplan.

We thought that a circle would work, we thought it had the right vibe, it seemed to fit and it carried a rich heritage, from symbolic Aboriginal ritual to icons of the Ideal City, precise graphics of the flag to the global sensibility of now.

Of course such vibes are not enough. We needed a design generator for the circle and, if possible, a single integrating means of making both formal urban space and a softening organic edge for Mounts Bay. We hoped to discover a singular, self-generating moment from which everything could emerge, everything seek interpretation, everything find conviction. This moment was the single drop of water creating iterations of waves, and then the realization of two drops, each making waves and generating interference patterns with each other. This felt like a beginning, a source and not just decoration; this seemed to weld the city and the water; it seemed to make a place we could call the Promenade, Event Space, Magnet, Centripetal Aspiration, something we really can call civitas, now not only a construction but the people, the community, the gregarious city.

The two source points generate waves that form an interference pattern at the entry to the circle and reflecting ripples along the foreshore of Mounts Bay. This interference we have interpreted as the gateway to the circle and, architecturally, as the prospect of a multi-bubbled building program. Meanwhile, along the new foreshore of Mounts Bay, we interpret reflection interference as both organic, rippling boardwalk and building mass configuration. It is to this self-generating formation that we have abandoned our composition, in which we hope to find prophetic advocacy, not merely design fantasies.

As for the scale of Perth city at the water, perhaps this is not entirely for us to tell. We aim to set the agenda, to envision the future, to sound a prophetic voice. Around the Circle we have allowed low-rise podiums, with all restaurants and shops at ground level and small apartments above. Then mid-rise towers to ninety metres ring the Circle, while back on the Esplanade commercial towers reach 200 metres. It is the spacing and location of volumes that must define the outcome.

Someone will say, “But where is the affordable housing? Where is the hospital? Where is the school? Where is the childcare?” Where indeed! But is Perth Foreshore the place for everything? We have not envisaged this place as the ideological response to all Perth afflictions; instead, we hope to give the city a source in the Swan River, to give it roots at the water’s edge and to make a place for everyone, a place to love.

Howard Raggatt is a director of ARM and design team leader for the LandCorp Perth Waterfront masterplan.

In response

Esplanade Square, which aims to “capture and enhance the bustle of the big city”.

Ground-level view of the River Circle, which will be ringed by restaurants and shops.

Evening view over the water from South Perth.

In 1992, in Melbourne, between stints at UWA, I reviewed the recently held competition for a new urban waterfront for Perth (1991) for Backlogue, the publication of the Half-Time Club. The competition sparked a great deal of interest in Melbourne, which was about to undergo great changes under Jeff Kennett – the Yarra South Bank being converted into a riverside promenade, and Docklands to be transformed into a new urban district. The Perth competition offered an opportunity for the application of architectural ideas on a large scale, and the brief called for strategic ideas for the entire waterfront as a mediation between the city and its river.

The Perth Foreshore Competition took place at a time of strong interest in urban issues, chiefly among European architects. This was not urbanism as we understand it now, but rather architecture committed to an urban scale – a socialist-inspired rationalism. The issues were debated in Casabella, Lotus, Quaderns and El Croquis – at that time socially committed journals. Koolhaas’s constructivist-inspired projects for Manhattan introduced a radicalism and critical agenda that sought to cut through the vapid conservatism clothed as contextualism that then characterized urban design thinking (now replaced by a desire for “funky” buildings).

In this context, the call for a new vision for central Perth seemed an ideal opportunity to challenge urban design orthodoxy. But was it?

The genesis of the competition was probably the Perth Foreshore study of the early 1980s: a collaboration between the state government and Perth City Council. The call was to make Perth a more livable city – Jan Gehl’s model of cobblestones and coffee shops – and to create a “unique image” for Perth. As part of this, the foreshore was to reconnect the city with its river, to enhance the social and civic environment of the city, and to “establish a symbolic focus dramatising the city’s aspirations for its growth into the 21st century”. The competition called for a landscape response – a setting within which buildings might or might not be inserted. An appendix to the brief documented surveys that had established that the public favoured the retention of informal public open space and opposed any waterfront buildings, or buildings or deck structures extending over the water. They strongly disapproved of a “lively waterfront atmosphere”, had little interest in seeing more of Government House, and opposed riverside car parking and the sinking, raising or widening of Riverside Drive. Passive recreation was approved; active or public events were opposed – as were fun-fairs, restaurants and tea-rooms, arts and crafts markets or workshops, museum, artworks and, most vehemently, a “water playground”. Clearly the public (and possibly the convenor?) wanted the space to stay more or less the way it was – a green belt separating city and river, contradicting the supposed intention of the project.

The judging panel reflected this emphasis: a landscaper, an engineer, an MIT-based academic with specialization in urban planning, a senior retired architect, and two laypeople with local knowledge. The winning team was entrant no. 78 – Carr, Lynch, Hack and Sandell (CLHS) of Cambridge Mass., USA. I didn’t know it at the time, but it is Kevin Lynch’s old firm.

What, then, was the outcome of the competition? After public scrutiny until the end of 1991, and a drawn-out exchange of contractual correspondence between the government and CLHS, the project foundered, amid undercurrents of opposition to a foreign firm being appointed (from the same town as the MIT professor assessor). The public did not seem to embrace the concept and its substantial changes to the current layout.

Under the subsequent Liberal government, an overall masterplan of the foreshore was not apparently pursued. However, isolated projects can be understood within the context of the competition brief: the conference centre on the foreshore next to the Narrows Interchange (fulfilling the 1990 City Vision call for a convention centre on the foreshore) and the Bell Tower, at the location where many competition schemes proposed a monumental terminus to Barrack Street. Neither project has been embraced by the public.

A subsequent question arises from this recent history of the Perth Foreshore and the strident public opposition to change. Should it be for “everyone”, or for a specialist interest group – an elite which can and will make use of this territory in an active way? This presupposes an urban population that will use the foreshore as its front yard, rather than viewing it as a familiar backdrop, at speed from the window of the Commodore.

The embrace of such gentrification seems to underlie the general tenor of Charles Landry’s recent invited critique of Perth, made as thinker in residence for Form’s Creative Capital program. Regarding the foreshore, Landry notes only that Perth does not engage with it well and needs to do something about that. But the site fits well with his mantra about complacency and acceptance of mediocrity, falling back on “lifestyle” and a city formed of roads and mediocre buildings. Landry argues that Perth should learn from Melbourne, Vancouver, Calgary, San Francisco, Austin, Boston, Copenhagen, Munich, Zürich, Barcelona, etc., etc., etc.

A dumb, morphological comparison reveals a commonality. All these cities have two sides facing a defined and constricted body of water. Space is finite, “architectural”. How then to deal with a city that seems to flow out to the horizon and is barely cognizable from the heights of Kings Park? Perth has an edge, which parallels the coast – on the edge of nothing. The 2004 report by Urbanizma for the Department of Planning and Infrastructure (DPI) presented strategies for the foreshore that largely restate the passive landscape emphases of the 1992 competition – public access to the river by pathways and north–south access routes, softening of the linear edge by informal projections and inlets, minimizing building and maximizing openness, and retaining Langley Park as a site for passive recreation. Has the DPI decided that the issue is simply too contentious to handle? It certainly doesn’t suggest that a dramatic transformation is on the cards.

Press of 18 February 2008: Following extensive public consultation, the former Melbourne enfants terribles Ashton Raggatt McDougall, with Richard Weller, have won a second competition to propose the future direction of central Perth and its river. Perth, fuelled by the mining boom, is exploding. Vaguely imagined phantasms of a possible city are projected through the media – shades of Greg Lynn, Jean Nouvel – fluid images of a strangely familiar architecture. But architects have a problem with the public. Architecture takes a long time to get right, generations. So why should we encourage such media snatches? In this case, because it is perhaps the best chance for a genuine commitment to an urban proposition that is not merely superficial, but might engage in a productive way with the entrenched and myopic attitudes of inbred locals. There should be no expectation that the provocative and imaginative images of the design team will lead to anything unless the WA Government is prepared to embrace the idea of Perth as a world city.

Behind the images, there is the proposition that the river should be brought back (excavating through the postwar landfill) to the city. We no longer believe in dead sites that depend on an annual (RSL) ritual to enliven them. Behind the images, the urban strategy of bringing the city to the water is sound. But, beyond form, there is an inevitable conclusion. No Australian city can deal with its waterfront without coming to terms with the reality that there needs to be an urban residential population. Without this the outcome will be a tawdry, distinctly Gold-Coast scraping of superficial urban gestures, fuelled by short-term tourism, without substance.

Nigel Westbrook is a senior lecturer in architecture at the University of Western Australia.

At a business lunch in February, Western Australian premier Alan Carpenter revealed dramatic redevelopment plans for central Perth’s Swan River foreshore, developed by a design consortium headed by ARM with Professor Richard Weller, Roberts Day Group and Hocking Planning and Architecture. The project is being managed by the State Government’s property developer LandCorp, but the private sector is expected to undertake much of the development work under strict guidelines. It is anticipated that the land sales will recuperate the State Government’s pledged $300 million for Stage One.

Expressions of interest were invited for the masterplan in May 2007 and the ARM consortium was appointed in August after LandCorp conducted a peer review workshop for shortlisted consortiums. A September business forum, again conducted by LandCorp, indicated significant business support. The resulting masterplan then underwent community comment in March this year. Assuming continued government support, the design team’s focus will now be on refining civic spaces, with the design of buildings in the hands of individual developers. LandCorp’s chief executive Ross Holt suggests that design guidelines will address sustainability, public realm enhancement and “aesthetics”. Major public works for Stage One are expected to start in 2011–12, with completion in 2015.

The grassy reclaimed land between the central city and the Swan River has for many years been viewed with two sets of eyes – one seeing a blight of untenable vacuousness, and the other seeing an idyllic and untouchable natural setting. Numerous redevelopment schemes have been proposed and denied over at least twenty years. The mindset that has spawned this conundrum is revealed in the FAQs section of the glossy Perth Waterfront website, which reads defensively. It is possible that without the process of questioning promoted by city dialogue programs such as Form’s Creative Capital, the momentum for government leadership and community acceptance of such vast changes may not have been created.

Since 1829, undercurrents of an Arcadian dream have wafted over Perth’s sandy flats. At colonization, Perth offered its investing class an opportunity to escape the “evils” of Great Britain’s cities and create their own world with wealth newly accrued from land acquisition. A parkland foreshore setting for the city began when the colonial botanist established a public garden on the site of today’s Stirling Gardens. A tradition of observing, rather than engaging with, the river has persisted ever since – Perth’s urban structure does not encourage the intense interaction of its citizens, but rather supports a lifestyle of quiet contentment. Population explosion is now unseating that tradition by force. The thrust of rock and gas extraction insists on hurtling Perth out of its isolated slumber, and into the reality of its role as a global city that can offer experiences as competitive as its salaries. Ongoing government commitment to quality public space and architecture at the Perth Waterfront will be crucial to the success of the redevelopment, which could be viewed as an experiment in sociology as much as in design.

Narelle Yabuka is a writer formerly based in Perth. She has worked with Form’s Creative Capital program and now works on Architecture Australia.

In the end, after many visits to the Perth Waterfront website, with its glossy imagery and Flash animations, I’m left feeling equal parts horror, bemusement and hope. Following many years of debate, design competitions and studios dedicated to reconfiguring Perth’s foreshore (with an obligatory cable car to Kings Park), there now seems to be a masterplan destined for implementation. Neatly enough, it comes during Perth’s latest resource-led boom, a time when the city is wealthy, growing and perhaps in a position to soothe its long-held, aching desire to feel like, and be regarded as, a “real” city. To what extent might the waterfront “vision” do this? Certainly the images suggest some planned strategic moves that are likely to help diversify and intensify the use of central Perth. None of these are startling to anyone slightly familiar with the debates over the foreshore and its connection to the city. The proposals for linkage spaces between St Georges Terrace and the foreshore, the reconfiguring of Riverside Drive to ameliorate the traffic and provide a better pedestrian environment, the provision of smaller-scaled public spaces, the integration with public transport nodes, the intensification of an inner-city residential population – all are fairly uncontroversial. What is controversial is that it has taken so long to realize any development.

But still there is the question of whether what unfolds will help to realize a more urbane Perth – shaking off the self-imposed “Dullsville” tag. That is far less certain. The vision presented – with its smoothly rendered montages of glistening cityscapes and a sultry narrator offering the “vibrant” and “dynamic” – suggests an environment overwhelmingly circumscribed by international development norms. Its waterside restaurants and cafes, residential towers and obligatory promenade are rendered ready to be dropped into any post-industrial city as property development and civic boosterism. The collection of other waterfront precedents on the website only reinforces the impression.

The eventual development process may or may not improve the palatability of the “vision”: adjustments to grain, scale, streetscape and so on may ameliorate the current images of a quite unresolved public realm. But what is also crucial to the broader question of Perth’s urbanity is the possibility and development of everyday practices of the city – “tactics”, to use Michel de Certeau’s term. The controlling desires of the vision – the neatly delineated, slick, homogeneous urban set piece – might be offset by a capacity for adaptation and flexibility, by less concentration on the spectacular form and more on infrastructural intensity. I would be heartened by a vision that allowed for the infiltration of more informal spatial practices – appropriations, resistances and evasions (beyond the vision’s perfunctory suggestion of “kiosks” on the promenade). Rather than the static diorama being presented, what might be generated is Kandinsky’s dream of “a great city built according to all the rules of architecture and then suddenly shaken by a force that defies all calculations.”¹

Dr Lee Stickells is a lecturer in architecture and urban design at the University of Sydney.

¹ Kandinsky quoted in Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Rendall (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988) 110.

Daring, bold, innovative. And long overdue. Could the redevelopment of the Perth foreshore be the big idea with which the city finally comes of age? At Form we are passionate about the Perth Waterfront project. When it finally happens, after a process of refinement, it will be something significant. It will be a symbol of leadership, vision and conviction – characteristics integral to the future success of Perth, which Form works to encourage through its Creative Capital initiative.

Many people are thinking about what this project signifies, what it will bring to Perth and its community. It will create opportunities and places for people, places that reintroduce us to the Swan River while creating a vibrant environment where we can interact, celebrate what makes Perth unique and feel a great sense of pride in our city.

Others are fixated on the high-rise, futuristic elements of the renders, fearing a Dubai-style skyline or the idea of a swan-shaped island. Some argue that improvements to health and education should take precedence over urban regeneration. On all counts they’re missing the point.

At this early yet critical stage, discussion of the waterfront project should not focus solely on the shape or height of the buildings, the islands or what everything might look like. It is about allowing the project to actually get off the ground by saying we need it – as a community, as a city and as a state. And by paying for the project through sales of development sites, rather than public funds, the government stands an excellent chance of making the whole enterprise cost-neutral in the longer term.

Thankfully, more and more people are beginning to understand that when comparisons are drawn with other great waterfront developments around the world, it is not being suggested that Perth become “another Melbourne” or “another Vancouver”.

The fervent debate illustrates how far Perth has come in waking up to the need to redefine itself. If this plan had been unveiled even two years ago, I doubt the resulting dialogue would have been as engaged or articulate. We have a booming economy, workers are flooding into the state, but any business leader will tell you that retaining talented staff is a huge challenge.

So what does Perth need to do to encourage that talent to stay? In my view, it badly needs developments like the waterfront project to succeed. Short-term thinking leads to inferior outcomes. Perth is operating in the international market; consequently, people’s expectations are high. They’re looking for vibrancy and amenity of an international standard. We don’t achieve those by playing safe, but by being ambitious and courageous – yes, and sometimes controversial.

The Perth Waterfront project is our chance to think big or lose a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. And when the development is completed, it’ll be one hell of a coming-of-age party for Perth.

Lynda Dorrington is the executive director of Form.

I am writing this from America, where I have been completing a book about how you make car-dependent cities more resilient in a future where we must reduce the need to travel by car. I have been giving presentations in Los Angeles, New York, Charlottesville, New Orleans, San Francisco and Portland. At each of these events I have told the story of Perth’s new rail system and the dramatic increases in patronage that we have seen. Most of all, I have been showing how the train is vital to the process of reshaping the city, as it creates a strong market opportunity for dense urbanism over and around stations. The first examples, such as Subiaco, have been medium-density and have helped to change perceptions about what Perth likes about urban development. The next phase of projects, such as those proposed at Northbridge Link, Cockburn Central, Stirling Centre, Belmont Park and Fremantle, are very exciting because they demonstrate that a new urbanism is becoming a significant option in our city. But nothing quite prepared me for the Perth Waterfront project, which is happening essentially because the Esplanade Station removed the William Street on-ramp and created a chance to link across to the river. I was emailed the story of the Perth Waterfront concept by my seventeen-year-old son, who was incredibly excited about it. “Finally, something really interesting in Perth” was his response. He also thought it looked more like Dubai than Perth, though. This was from a young person who has travelled a lot and always found dense urbanism to be the most attractive element in any city and who wonders why we have been so reluctant to be more adventurous in Perth in the past. I think he represents something about the new Perth. We are not a sleepy country town anymore, but want more urbanism. Whether we can go as far as adopting something as adventurous as this is very uncertain. I know the conservative bureaucracy will give it a hard time, as they did with Belmont Park, which has had to be scaled down purely because it offends a few of their suburban sensibilities. I am a great supporter of the concept for Perth Waterfront, but our history in Perth is to scale down such ideas. I hope we can do better over this one. It sure beats a freeway on-ramp as a contribution to a more sustainable, resilient city.

Peter Newman is professor of sustainability at Curtin University of Technology.

The Perth Waterfront proposal can be found at

www.perthwaterfront.com.au.