TABULA RASA OR DÉJÀ VU?

Victoria Bridge Demonstration Area, from the Draft Brisbane City Centre Masterplan.

Three-dimensional city form view, from the same document.

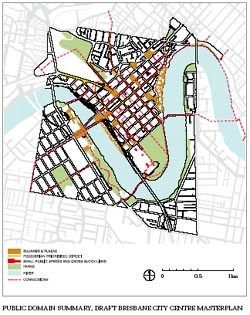

Public domain summary, Draft Brisbane City Centre Masterplan.

As a city spreads without a plan, villages are engulfed, good farming land low and unsuitable for residence is sacrificed, open spaces disappear, and costly mains providing the public utilities have to be enlarged and duplicated. The only possible solution to this problem is to limit the spread of the city, as a homogenous mass, and to guide further growth into separated satellite towns and suburbs, divided from the main city by continuous open spaces. Where land is suitable for farming it can be zoned as ‘Rural’. Brisbane has a unique opportunity at present to obtain a Green Belt round the city as it exists at present, with a minimum of expenditure.

City Planner McInnes,

“Memorandum to the Lord Mayor”, 1941.

Brisbane City Archive 460/52/4.

The aspirations of city planner McInnes in the 1940s seem oddly familiar in 2005. Little survives of the Green Belt once imagined for Brisbane, but the desire to define the extent of urban development remains.

This year has seen the release of two major planning documents – the South East Queensland Regional Plan and the Draft Brisbane City Centre Masterplan.

Important infrastructure projects are also under way, including the Inner Northern Busway (INB) and the controversial TransApex road tunnel scheme cherished by the Lord Mayor. With the regional population expected to increase to nearly four million over the next twenty years, growth management has become a political issue. What form might the future take and how might the profession contribute to this real-time D&C debate?

The 200 kilometre conurbation, described by some as the two-hour city, stretches from Noosa to the Tweed and was the focus of many workshops, exhibitions and debates surrounding the release of the Draft South East Queensland Regional Plan in September 2004.

Gazetted in June, this document belatedly gives the state government statutory authority to direct future metropolitan growth and an Office of Urban Management (OUM) has been created to coordinate and facilitate its implementation. Similar to the “compact city” or Smart Growth strategies under way in other Australian cities, the Regional Plan limits horizontal expansion by defining an Urban Footprint and a twenty-year target of 575,000 new dwellings has been set based on current annual growth. Half these dwellings will be in Brisbane and the Gold Coast, with 80 percent of those in Brisbane being attached infill dwellings. To meet these targets, 6,000 new apartments or attached houses will need to be constructed annually.

City form and city culture will radically change as a result. Brownfield sites earmarked for development are, predictably, Transit Oriented Developments (TOD) and Activity Corridors (AC). While the goals may be laudable, the targeted redevelopment sites require considered investigation. Most of these middle-ring suburbs have fragmented land-holdings, character housing areas and traffic noise, and are deficient in publicly accessible open space. The speed at which these policies are to be implemented is also of concern, given the real danger of creating spaces with good transport connectivity but poor physical amenity. The Local Growth Management Strategy (LGMS) required under the Regional Plan is currently in preparation and the Brisbane City Council has commissioned studies, held workshops and conducted extensive community consultations. The guidance of international experts such as Larry Beasley (Vancouver), Steven Ames (Portland) and Jan Gehl (Copenhagen) was also sought.

In this context, and at the instigation of Ed Haysom and the Brisbane Development Association, a one-day workshop entitled Tabula Rasa was held to reflect on the city’s possible futures. Multidisciplinary teams assembled were led by Michael Rayner (Cox Rayner), James Coutts (EDAW), Stephen Calhoun (TRACT) and Andrew Wilson (QUT). The challenge set was to create an innovative, sustainable and “distinctly Brisbane” city for a population of two million starting from a clean slate. Identity and sustainability are clearly the mantras of the twenty-first century and proposals ranged from a radial model with high-density coastal/rural nodes (Rayner) to a polycentric region separated by fingers of vegetation (Calhoun), a linear city of interconnected villages (Coutts) and the lyrical “pineapple-top” strategy of dense hilltowns (QUT).

All schemes contained recreational and productive agricultural lands in the revisioned green belts, complete with artificial aquifers and wetlands for total water cycle management. Of note was the reticence to entirely erase the existing city, particularly the CBD.

Was this the result of urban “change fatigue”, or a natural response to the identity question? After all, even Corb couldn’t bring himself to entirely demolish Paris and gothic gems survive among the towers of the Plan Voisin. The current location of Brisbane’s city centre is photogenic, with many close-range lookouts for the city to admire itself from. In an age where consumption has surpassed production as the primary urban activity, spectacle is a critical part of civic identity.

The new Brisbane is adjusting to its “fledgling urbanity” but still suffers as a city that visitors pass through on their way to the beach. Despite an upsurge in inner city residents and extensive redevelopment of the Queen Street Mall, the CBD can hardly be described as an attraction. The Brisbane City Council recognizes these issues and has commissioned architect/urbanist Trevor Reddacliff, who directed the transformation of inner city New Farm and Teneriffe, to oversee the renewal of the city centre with Donovan Hill working as principal design consultant in partnership with the BCC.

This collaboration resulted in the Draft City Centre Masterplan, released last September. Framed as a set of vision principles or qualities accompanied by implementation strategies, the masterplan contains high-rise development to the peninsular and aims to achieve high-quality public domain and design outcomes through both small-scale adjustments and major demonstration projects at strategic locations.

The masterplan seeks to enable a progressive “ownership” of this vision by stakeholders, government and the community through consultative processes. This is important as the long-held rivalry between City Hall and the state government has thwarted many fine proposals and a lack of shared purpose has undermined the urban integration of major infrastructure projects in the past.

Donovan Hill studied exemplar cities and the processes they employed to achieve their desired outcomes. This study informed their recommendation to create three key advisory boards. A City Centre Implementation Committee will provide strategic direction and leadership in the implementation and coordination of the masterplan, with both municipal and state government representation. This is to be supported by a Design Excellence Panel of external experts and a dedicated team of council officers responsible for the day-to-day facilitation of the plan known as the Public Domain Group.

Donovan Hill studied exemplar cities and the processes they employed to achieve their desired outcomes. This study informed their recommendation to create three key advisory boards. A City Centre Implementation Committee will provide strategic direction and leadership in the implementation and coordination of the masterplan, with both municipal and state government representation. This is to be supported by a Design Excellence Panel of external experts and a dedicated team of council officers responsible for the day-to-day facilitation of the plan known as the Public Domain Group.

The masterplan continues a lineage of “beautification” strategies for the city centre, despite being of far greater scope than any previous project.

Competing on a national and international level for its share of business investment and the international student and tourism markets, the individual personality and vibrancy of a city centre have become an economic imperative dictated by consumer choice.

No city worth mentioning ever sleeps in the twenty-first century, as urban life becomes both spectacle and entertainment. A recent television commercial commissioned by Brisbane Marketing testifies to this evolution. Called “yes, it’s a sleepy little town”, the advertisement features the city by night.

The rating of a city’s qualities and its comparative “livability” has become a major force in urban economies, with the potential to radically shape their futures. The city as consumer product is a reality of the twenty-first century.

More than ever architects will be called upon as “change agents” to advise on new configurations and ways of experiencing Australian cities as our populations and markets evolve. Collaborative research engaging academia, the profession and urban development stakeholders is more important than ever and the sharing of knowledge and experiences between cities with forums, competitions and debates are all required to adequately address the issues at hand.

The impacts of these changes will not be judged in next year’s awards but by the future equivalent of a threadbare Green Belt.