WHAT IS AN APPROPRIATE CONTEMPORARY URBAN ARCHITECTURE FOR THE TROPICS? DAVID BRIDGMAN CONSIDERS DARWIN COVE CONSORTIUM’S WINNING MASTER PLAN FOR THE REDEVELOPMENT OF DARWIN’S PORT.

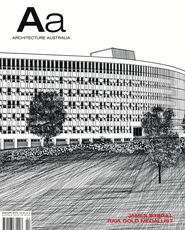

View of the convention centre and surrounding landscape.

Darwin Cove Consortium’s winning master plan, overview with the city beyond.

Stage 1 of the draft master plan, which includes the convention centre, hotel, residential apartments and significant public facilities.

Stage 2, which includes the development of the residential precincts of Fort Hill, Kitchener Bay and Stokes Hill.

Section through the cove, looking toward the finger wharf residential developments.

Section showing the elevated walkway that will connect the port back to the city centre.

DARWIN, IN THE tropical north of Australia, is often constructed as “different” in relation to the rest of Australia. John George Knight, Darwin’s first architect, writing in the late nineteenth century, confessed that he had “adduced sufficient evidence to show that an Architect on his arrival in the Northern Territory must begin his studies anew … here”. He commented, “I find it necessary to ignore much of my acquired knowledge and to make a fresh and especial study of my immediate surroundings.” Knight discovered that in the tropics the climate is ignored at the expense of good architecture. What, then, would be an appropriate architectural response for the most tropical of Australia’s capital cities?

This is one of the more significant questions concerning a major revitalization project for Darwin’s waterfront. The one-billion-dollar Darwin City Waterfront project has stirred up considerable controversy among the profession and the public in general since last September, when the Darwin Cove Consortium, headed by ABN Amro, was selected as the preferred developer. Designed by Hassell as principal architects and master planners – with Crawford Architects/TVS, who are responsible for designing the convention centre, and the local firm of MKEA – the redevelopment of Darwin’s waterfront is an exciting and ambitious project with the potential to redefine the city over the next ten years.

The project is centred on Darwin’s port: a 25-hectare site nestling along the base of the steep escarpment on which the city is built. Although physically separate from the city centre, the port is inextricably linked with the historical development of Darwin. Here, on the traditional land of the Larrakia, G.W. Goyder established his survey camp in 1869 and proceeded to set out the town that would become Darwin. As the main supply point for the region, the port slowly expanded to include a wharf, railway terminus and refuelling facilities for the navy. It was the scene of considerable destruction during World War II and, in more recent times, was an important facility for the Territory’s pastoral and mining industries. Darwin’s history is writ large on this small piece of land.

With the relocation of commercial activities to a new wharf constructed at East Arm, Darwin’s port became a much-coveted site for redevelopment. Although the port remains operational, it now caters for passenger and other non-commercial shipping. Cafes, restaurants and retail outlets along the main wharf make it a popular destination for visitors and locals alike.

Eighteen months ago the Northern Territory Government announced that a “world-class” convention and exhibition centre would be the centrepiece of a proposed redevelopment of Darwin’s waterfront. The site was to be developed under a partnering arrangement between the Government and a private consortium, with expressions of interest called in late 2003. From eleven responses three consortia were chosen to develop and submit a proposal. These were the Darwin Cove Consortium, headed by ABN Amro and the Walker Corporation; Wharflink, headed by Macquarie Bank and Leighton Contractors; and the Multiplex Consortium, headed by Multiplex.

While each of the consortia prepared a comprehensive master plan, only the preferred proposal has been made public. This is unfortunate, as it prevents informed debate on the merits of alternative proposals, but as the selection criteria included considerably more than design merit alone, it is perhaps an understandable decision. In selecting the Darwin Cove Consortium as the preferred developer, Darwin’s Chief Minister noted that they “best met the overall requirements when considering the criteria in areas like the master plan, design and functionality of the convention centre, financial requirements, local industry participation and community expectations.”

The master plan establishes the long-term vision for a site that stretches from the long-since levelled Fort Hill, at the base of Government House, around to Stokes Hill at the eastern extremity of the site. The concept expressed in the master plan is a series of residential apartments stretching out into the water, forming in effect “finger wharves”, with more conservative mixed-height residential development located at either end of the site. The focus of the master plan, and the development itself, is a 1,500-seat convention centre incorporating 4,000 square metres of exhibition space, located adjacent to the main wharf access road. The position of the convention centre, framing the public space of the development, is one of the key aspects of the master plan.

Public facilities are provided immediately in front and to the west of the convention centre and include a wave pool, safe swimming areas, an amphitheatre, a historical and cultural centre and waterfront promenades. A significant seawall encloses the waterfront to compensate for Darwin’s eight-metre tidal range, which would otherwise expose unsightly mudflats in front of the development at low tide.

The first stage, located more or less in the centre of the site, is programmed to begin this year. It includes the convention centre, hotel, residential apartments and significant public facilities. Other stages, comprising the residential precincts of Fort Hill, Kitchener Bay and Stokes Hill, will be developed in due course.

For Darwin this is one of the most ambitious and important urban renewal projects ever undertaken and, understandably, it has given rise to considerable controversy. While it has much support, it also has its critics, and many aspects of the master plan have been questioned. Much of the present criticism, however, has focused on detail and overlooks the fact that the project is at master plan stage.

In particular, the design of the various buildings has come under fire for the lack of attention to “tropical” detailing – seen in the minimal roof overhangs, omission of shading to walls and glass, inadequate ventilation and so on. This critique is somewhat premature at this stage and particularly unfair to the architects. With significant development of the architecture to be undertaken over the coming months, these details will, no doubt, be addressed.

Nevertheless, some important points have been raised in relation to the broad master planning that warrant further discussion. The density of the overall development is one such aspect, particularly in relation to vehicular circulation along the single access road and the overall impact of the development on the site. The height of the various buildings in relation to the escarpment and their encroachment on sightlines from existing developments along the esplanade has caused concern, with some adjustment to the building envelopes currently being made. The proposal for large residential tower blocks in the Stokes Hill precinct is also considered by many to be unwarranted.

The residential apartments forming the “finger wharves” have been criticized for potentially forming an undesirable first impression of the city for passengers arriving at the wharf by cruise ship. But are these tendrils stretching out into the sea really so undesirable? While their density at the water’s edge may be of concern, they are well positioned to frame views of the escarpment from the deck lounge of most cruise ships likely to visit Darwin. Of equal importance is the view from the esplanade down to the port, and it would seem that these views are facilitated, rather than impeded, by the wide open spaces between the long thin buildings.

One of the least convincing elements of the master plan, however, is the connection back to the city centre. The vertical separation between the city and the port is an obstacle that has proved insurmountable in many earlier proposals. While here it has not been overlooked, the elevated walkway provides a less than ideal solution to a very complex and difficult problem and it is hoped that the whole pedestrian sequence from the CBD to the port will be reviewed and strengthened as the design develops. While the visual and experiential aspects of this connection are important, it will also prove vital for the long-term commercial success of an already struggling CBD.

Reservations have also been voiced about the design of the convention centre. These are being addressed as stage 1 of the project is developed. As the largest single building element on the site, the convention centre will have considerable visual impact, particularly as it will be seen from all sides as well as from above. As such, it will be a significant element in the overall design and one that will contribute greatly to the success of the waterfront development as a work of architecture.

The expression of interest document called for a project that would “reflect the exotic and unique differences that the tropical climate, history, culture and proximity to Asia have carved into the fabric and life of Darwin”. This highly significant and large-scale project provides a unique opportunity to establish a relevant architectural expression for the northern tropics. This is not to suggest a return to some regional vernacular. Rather, it provides the opportunity to develop a more contemporary architectural idiom for the twenty-first century attuned to the specificity of place and culture yet set within a broader environmental discourse. Here in Darwin we wait in eager anticipation as stage 1 is developed and these somewhat amorphous forms take shape and their detail becomes clearer.

DAVID BRIDGMAN IS A PRACTISING ARCHITECT BASED IN DARWIN AND A PHD CANDIDATE AT RMIT UNIVERSITY.