Considering the ever-expanding nature of educational facilities today, we need, in the first instance, to ask how a new addition accommodates the existing milieu of a campus. Setting aside the idea of contextual harmony, campus architecture – particularly when buildings have been added in different periods – should contribute to the spatial life of the existing situation. A new addition should also say something about the design’s contemporaneity. This last attribute is of critical importance for campuses that are in close proximity to an urban area that is itself subject to constant redevelopment. This is true of the campus of the University of Technology Sydney (UTS), which, like many other universities, has chosen to follow the path of Vitra Design Museum in commissioning a group of well-regarded architects to add their signature marks to the museum’s site. Today, most universities compete with one another based on their financial capacity to attract prospective students with a collection of diverse and well-designed buildings, considered “jewels” added to the body of a campus. At UTS, the challenge has been not only to commission domestic or internationally well-known architects for these projects, but also to work with a campus morphology that is interwoven with one of the fastest-growing precincts of the city of Sydney: Central Park.

UTS Central by FJMT.

Image: Tyrone Branigan

An early signature work that marked the anticipated morphological fabric of the campus was the UTS Tower by Michael Dysart from the New South Wales Government Architect’s Office, designed in 1964 and completed in 1979. One of the latest additions to the UTS campus is FJMT’s UTS Central: a student hub, towering next to the existing tower. In different ways, each of these two buildings mediates between the campus and its urban enclave, yet there is more to the dialogue between them. Having stood alone for 40 years, the old tower now seems to tango with the new one, which was conceived, according to FJMT director Richard Francis-Jones, as “a sister to a big brother.” The analogy between architecture and the body is not new, and the old and the new towers are indeed like bodies soaring next to each other, the spatial gap between them alluding to the internal Gestalt of each building. But FJMT’s building re-envisions the dialectic of city and campus in more ways than one. Stepping into the main entry, one can’t dismiss the design’s progressive adjustment of its geometry from the campus grid of Alumni Green at its lower levels to the city grid of Broadway at its upper levels.

The podium – which includes a learning commons, library, reading room, collaborative classrooms, general teaching spaces and student services – overlooks Alumni Green.

Image: Tyrone Branigan

Putting aside the body analogy, the differences between these two towers should be mapped in reference to the historicity of contemporary architecture. While the earlier tower has been rightfully associated with the brutalism of its time, the genesis of FJMT’s decision to wrap the building entirely with glass can be extended back to Die Glaserne Kette ( The Glass Chain ), a series of letters written by members of a secret group founded by Bruno Taut in 1920 (a century ago, to be exact) in collaboration with prominent architects including Walter Gropius. And yet, clad in glass, the Central Tower looks like a solid diamond – perhaps in the spirit of Erich Mendelsohn’s Einstein tower, a convincing analogy thanks to special techniques now available for double glazing, the aesthetics of which exceed the painterly transparencies associated with the modernist use of large glazing. The design is also not expressionist, in spite of evidence that a few recent works of FJMT tend toward formal exploration that might demonstrate the influence of digital design techniques. I note this in order to show that site-specific formal and spatial explorations, in conjunction with design that explores the relationship between the organic and the biomorphic, have been familiar exercises in the firm’s portfolio. The twisting and soaring tower of UTS Central is edited in reference to the regulating lines of both the frontal urban street and the UTS campus, while the geometry and cuts of the highly detailed and operable louvre shading system of the Reading Room facade draw from the dialectics of organic and mechanic extant in nature.

The building’s upper levels take the form of a tower that twists and rotates as it climbs, responding to the surrounding building and site geometries.

Image: John Gollings

As noted earlier, UTS Central looks “solid” and yet feels light, not only because of the materiality of its dressing but also – and perhaps more importantly – because it is seemingly conceived of as a container. Analogous to the internal organization of the body, this concept of the container embraces diverse functions or organs, while the space in between operates as a hybrid of served and service spaces. The building’s circulatory system simultaneously separates and connects the different components of the brief. The highlight of this system is a double-helix stairway that runs up four levels and, like a hinge, establishes a dynamic rapport between the building’s interior spaces and the surrounding urban context. In addition to this spectacular staircase, the public dimension of the design’s circulatory system is complemented by the visibility of a pair of escalators, though at the expense of the elevators, which remain almost invisible. While the building responds to the primary requirements of the brief, it is the design’s hybrid spaces that are the progenitors of “event space.” In addition to housing the university’s main library – which is undoubtedly one of the highlights of the design – UTS Central also contains large innovative and collaborative classrooms, a super laboratory for science students, and, on its upper floors – the faculties of engineering, IT and law. On entering the public level, the building’s soaring internal volume operates like a diorama through which the spectator can register and enjoy almost 360-degree views of the building’s surroundings. In particular, it provides a close-up and above-street-level view of the UTS Tower, along Broadway, into Central Park and, more importantly, into the quadrangle of Alumni Green. To the credit of FJMT, the building pumps new life into the two existing lateral buildings, and to the Vicki Sara Building to its north, designed by Durbach Block Jaggers in association with BVN Architecture.

The triple-height atrium of the Reading Room is topped by a large skylight while the glass facade maximizes light and employs operable louvres for shading.

Image: Andy Roberts

These attributes disclose two design strategies. The first of these was to limit the campus/city dialogue. The building’s interior is not accessible from Broadway; instead, and in contrast to the UTS Tower, the main entrances are from Jones Street and the Alumni Green quadrangle, which serves both the old and the new towers. The second design strategy was to complement the gestural profile of the podium’s linear and transparent glass enclosure on the Broadway side, designed in collaboration with Lacoste and Stevenson and DJRD. As a result, the podium merges with the ribbon-like bands of the tower – although the bands, interestingly enough, are discontinued above the building’s main entrance. Here, the insinuated surface cut makes an opening to accommodate a different language of stacked floors, perhaps in reference to the language of the old tower, and deconstructs the conventions of frontality with interesting urban connotations. The new addition turns the existing Jones Street into an urban alley and entry to the UTS campus, while consolidating the typological geometry of the Alumni Green quadrangle and the helix-shaped internal stair, a hinge between architecture and the city. A quick examination of the internal organization of the design endorses the placement of this stair, the most theatrical architectonic element of the design. The hinge also short-circuits the uniformity of the podium on which part of the tower sits. On the north side, this three-storey podium contains the Reading Room and is stretched like an exaggerated lintel with the main entrance beneath it.

Much could be said about the precision of the detailing, the ways that the curved ribbon-glass enclosure is held together and the building’s support system. These elements are important and should be discussed properly, but in the space left, I would rather mention three highlights of FJMT’s design: the library, a delightful space of learning surrounded by a wall of books but also open to an outside terrace; the idea of event space that is centred on the building’s circulatory system; and the diorama, which makes the porosity of the building’s served/service spaces meaningful. Most importantly, while transforming the morphology of the UTS campus, FJMT’s design is a feat in recoding the campus architecture typology: it incorporates and distributes certain aspects of a well-conceived academic environment both vertically and horizontally, to the extent that the interior of this unique container becomes an analogue of the campus itself. The work thus exceeds the premises of architecture and is an exhilarating mediator between the campus and the city.

Credits

- Project

- UTS Central

- Architect

- fjmtstudio

Australia

- Project Team

- Project team: Richard Francis-Jones, James Perry, Elizabeth Carpenter, Daniel Karamaneas, Aliaksei Sakalouski, Gema Edo, Borja Pedrosa, John Perry, Cassandra Halpin-Smyth, Pei-Lin Cheah, Anna Szymanska, Michael Woodward, Brooke Matthews, Alessandro Rossi, Sean Pettet, Owen Sharp, Noel Yaxley, Cassandra Cutler, Diana Rivero, Interiors team: Lina Sjögren, Mariska, Margaret Metchev, Prayrika Mathur, Miyo Stanton, Lauren Saull, Bianca Laurence, Landscape team: Phoebe Pape, Richard Tripolone, Maria Martinez, Francesca Cazzetta

- Consultants

-

Acoustic consultant

Acoustic Studio

ESD and mechanical engineer Steensen Varming

Electrical engineer JHA Consulting Engineers

Facade Surface Design

Fire engineer Arup

MEP engineer Steensen Varming

Original Broadway podium design Lacoste and Stevenson with DJRD

Structural engineer AECOM

- Aboriginal Nation

- UTS Central is built on the land of the Gadigal people of the Eora nation.

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2019

Category Education

Type Universities / colleges

Source

Project

Published online: 8 Sep 2020

Words:

Gevork Hartoonian

Images:

Andy Roberts,

John Gollings,

Richard Francis-Jones,

Rodrigo Vargas,

Tyrone Branigan

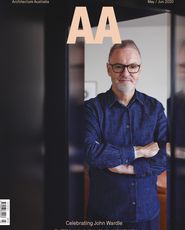

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2020