It’s rare that a hunt for a famous architect leads to a place with a name like Wombat Bottom. And yet, 80 kilometres from Adelaide, in a hilltop farmhouse named after the derrière of a stubby marsupial, lived the late John Neville Morphett AM OBE, who brought the teachings of the Bauhaus movement to this southern continent and turned a small architecture studio – Hassell – into one of the world’s great multidisciplinary design practices.

In 2013, John Morphett and his wife Vivienne invited me to join them in the final building he designed and the first he built: their stone home near Port Elliot, which has windows that stretch from near the floor to a ceiling formed of 100 doors taken from an old hotel. Outside, kangaroos and alpacas grazed on a gum tree-dotted pasture that rolls down to the gentle waters of Encounter Bay.

Morphett, who died aged 83 on 25 March 2016, sat among the pantheon of our nation’s architects. The Royal Australian Institute of Architects gold medallist (2000) could have stolen the limelight and fashioned himself as a kind of “starchitect,” but his commitment to the “unity in diversity” credo of his teacher and friend Walter Gropius and the Bauhaus movement instead saw him create an interdisciplinary practice that could call on expertise covering interior and landscape design, urban and town planning and environmental-impact assessment.

Born in Malaysia in 1932, Morphett’s family was forced to flee to Perth during World War II. His dad, John snr, didn’t travel back with them.

“I didn’t see much of my dad, during the war he was in the navy and we were sort of refugees in Perth – my mother’s family came from there. We got sent down from Malaya. We got kicked out by the Japanese. So I went to school in Perth, and then after the war my father went back to Malaya. So I just went up there in my school holidays. He died when I was I quite young. He was just 49.”

A good student, Morphett moved to Adelaide at age 14 because, even as a teenager, he knew he wanted to be an architect, and Adelaide was one of the few places he could study architecture. On finishing high school, he earned a place in 1951 at both Adelaide University and the School of Mines and Industries (now part of the University of South Australia). A star pupil, he was hired by Hassell founder Colin Hassell (when the firm was known as Hassell, McConnell and Partners) before graduating.

Opposed to the stuffy established architectural order in Adelaide, the young Morphett joined forces with a group of design rebels – the Contemporary Architects Association.

“All the oldies, the established architects, were doing Classical work and Gothic Revival. Some who were more adventurous were doing a bit of modern work, but none of them were modern architects,” said Morphett, “so we thought we’d give the modern architecture movement a push.”

The Contemporary Architects Association’s biggest effort was an exhibition held in Adelaide’s Botanic Park in 1956, for which full-scale models were built in concrete, glass and steel – a radical proposal in what was a city of red brick and sandstone. The then-dean of Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) School of Architecture, Pietro Belluschi – in Adelaide to speak at the Australian Architectural Convention – was drawn to the exhibition. “I went straight up to him and asked him if could I do a master’s degree at his place,” Morphett said, smiling at his youthful audacity.

The answer came in the form of an Albert Kahn Fellowship, and it saw Morphett complete a master’s degree at MIT in the presence of the leaders of the modernist movement: Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier (“he gave us a talk in French that I couldn’t understand”), Frank Lloyd Wright, Eduardo Catalano, Philip Johnson and Richard Neutra.

Bauhaus founder Gropius took the young Australian on in 1957 as a member of The Architects’ Collaborative (TAC) – the German’s architectural firm based in Massachusetts. Morphett quickly rose through the ranks, gaining a key position on the team that designed New York’s Pan Am skyscraper (now the MetLife Building) above Grand Central Station.

“I used to go down to New York City once a week as Gropius’s representative,” said Morphett. “That’s where I learnt about the New York lunch: two or three martinis and a sandwich!”

But a bigger job was to come – that of co-designer with Gropius of the University of Baghdad, which still stands on the banks of the Tigris, despite “shock and awe.”

“This was before the days of intense cultural awareness, which is much more prevalent today. So I think we probably would have done it differently today. It was a marriage of modernism with Arab culture, and the modernist movement was a little bit uncompromising in the sense that it wanted to do what Corbusier said – a building is a machine for living – so it had this sort of very pragmatic, practical view of enclosing functions. No decoration, none of the old Arab arches and tiles and all that stuff. We didn’t go in for that.” While Morphett looked back at his work on the campus with some reservations, the experience of working alongside 74-year-old Gropius was entirely positive.

“From the Bauhaus days back in Germany, Gropius instilled in everybody the idea that architecture is a complex art. You have to take into account a whole lot of issues – social, environmental … So it was much better to learn to work as a collaborator than to try to be the master craftsman who did everything and knew everything,” Morphett recounted.

In 1962, after spending two years in Rome documenting the University of Baghdad campus, Morphett returned to Adelaide and Hassell, McConnell and Partners. Morphett’s modernist, Bauhaus learnings appealed to Colin Hassell, but grated with partner Jack “Mac” McConnell who rejected modernism per se (despite his work having much in common with it) and had an autocratic approach to design. Eight years later, McConnell was asked to leave the partnership and the firm became Hassell and Partners.

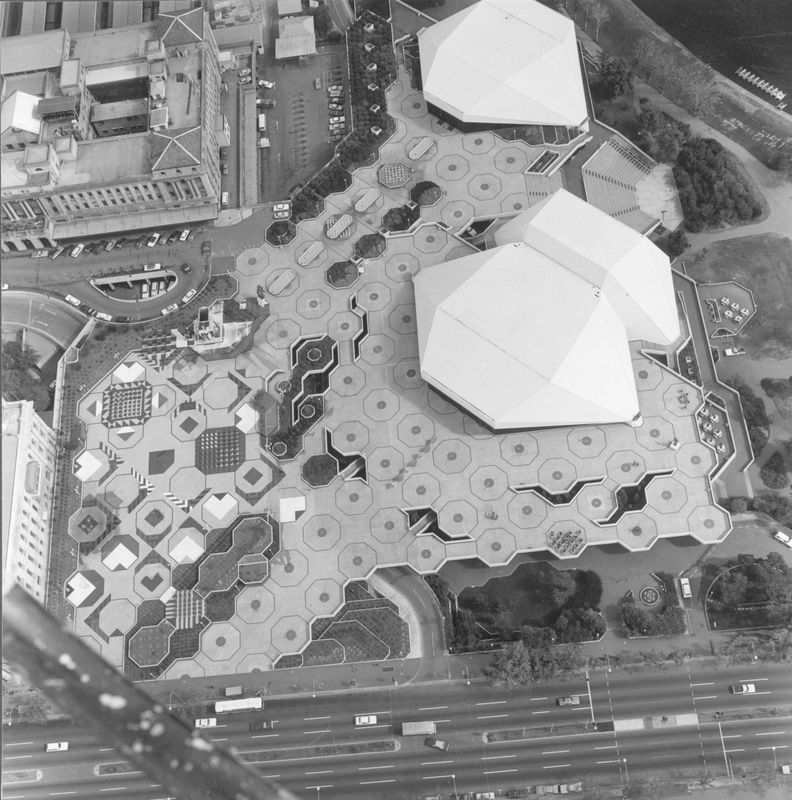

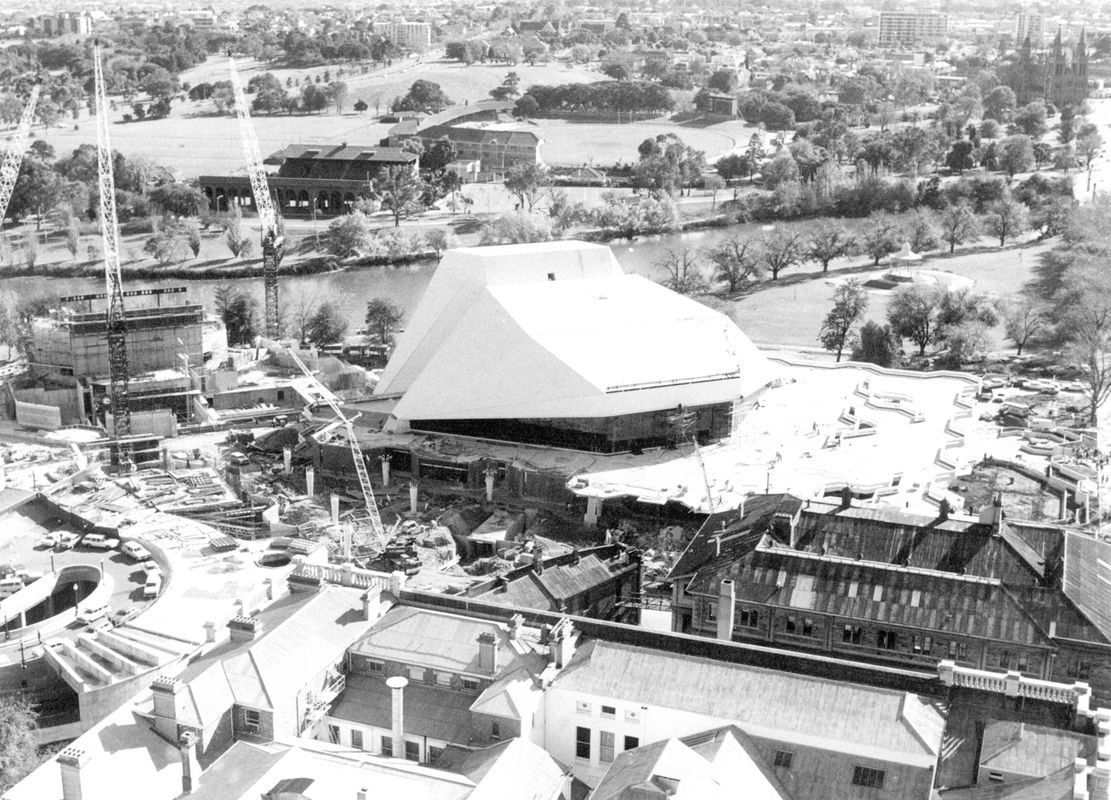

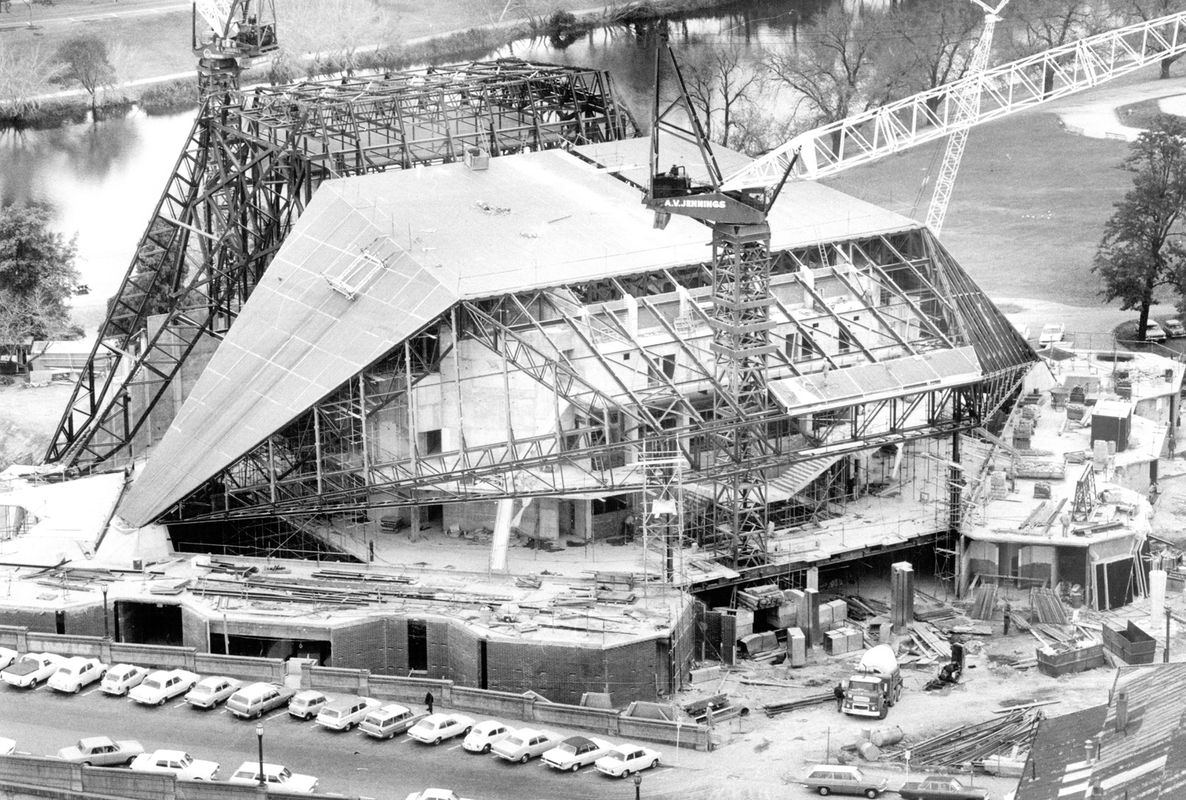

In 1970, Hassell tasked Morphett with designing the Adelaide Festival Centre – a 2000-seat theatre on the southern bank of the River Torrens, which skirts Adelaide’s city centre. Morphett had prepared for the commission by visiting the world’s greatest theatres – an incredible journey that saw him take in 42 halls in 42 days. It taught him that great theatres are designed from the inside out.

Adelaide Festival Centre, Hassell (1965–80).

Image: Peter Bennetts

Morphett designed the building quickly, opting for two white octagonal shells in concrete. “I didn’t do many designs for the place. It was remarkably simple. I went home one night and built a little cardboard model and I thought that it might work. We refined it, but initially it was essentially as it came out.

“The design encloses fairly logically the functions inside,” he explained. “You need an auditorium, you need a stage, so you put a different shell over each one and where they join is critical – the proscenium line is expressed where the volumes meet.”

The Festival Centre, Australia’s first multi-venue performing arts space, was officially opened on 2 June 1973. “The Festival Centre is a milestone project,” said Hassell principal Mariano de Duonni. “It’s sculptural, it’s beautiful and it’s simple. John instilled in me that clarity of thought.”

The Festival Centre could have been a one-off success, but Hassell and Morphett then set about engineering a better architectural practice. Gropius’s commitment to peer review and voluntary teamwork was embraced.

“Any organization comprising so many different skills will always have tension points. Hassell’s secret is that [it doesn’t] see that as a negative. So you’re constantly negotiating a fluid state. Welcome to the twenty-first-century practice,” said former Hassell architect Tim Horton (now registrar at the NSW Architects Registration Board), who led the refurbishment of one of the Festival Centre theatres in 2010.

Melbourne Central, Kisho Kurokawa, Bates Smart McCutcheon and Hassell.

Image: Photographer unknown

But Morphett’s tendency to push for collaboration and eschew the idea of the all-knowing architect didn’t preclude working alongside starchitects. Japanese architect and co-founder of the Metabolist movement Kisho Kurokawa joined a Morphett-led team in 1986 to design Melbourne Central – a retail space best known for its tall glass conical spire, which encases the heritage-listed Coop’s Shot Tower. Morphett, the diplomat, enjoyed the creative tension of working across cultures.

“Kurokawa was not too hard to work with. He was very polite and very proper all the time. But he wanted to do things his way,” Morphett said. “He wasn’t really a modernist, he was fairly unique, but he did some good work. And on one of the occasions when we were in Japan, he was kind enough to fly us around to some of the other parts of Japan. He did a nice project down in Fukuoka. He was married to a famous actress [Ayako Wakao], so they lived in the top levels of the art world. He came out to Melbourne on two or three occasions.”

Embracing internal and external collaboration, and working across the world with as many as four studios on a single project, saw Hassell cleverly ride out the global financial crisis of 2007–08.

“I think it has helped Hassell survive as a firm, and not just survive but prosper,” said Morphett, who served as the firm’s managing director from 1979 and board director from 1992. “It also has ensured that there’ll be succession within the firm and it won’t die with any individual.”

With Morphett’s passing it’s a chance to reflect on a lifetime of good work – secure in the knowledge that the accomplishments of this humble yet brilliant architect will indeed endure.