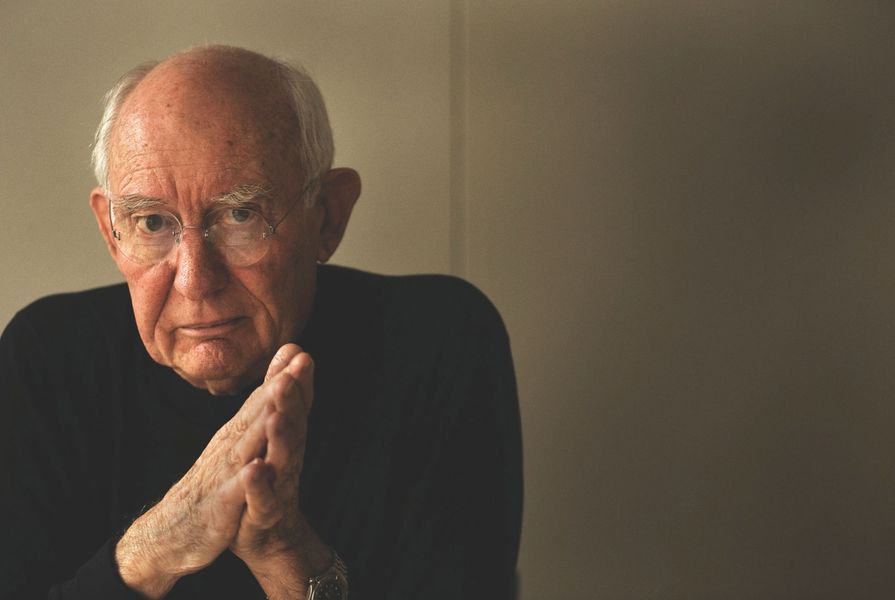

Ken Woolley was the most complete architect of the modern era in Australia. He designed buildings of every type and scale – from small homes and project houses to office towers, apartments, churches, corporate headquarters and civic squares, for public and private clients from prestigious to poor. He was the quintessential Sydney architect; almost all of his work can be found within forty kilometres of the Sydney Town Hall (for which he designed an office tower and public square). He was a founder of the “The Sydney School” in houses, and notably his AS Hook RAIA Gold Medal address in 1994 was entitled “State of the Art in Sydney”. Every building he designed was different (there being no “starchitect” repetition or house style) but every one seems right for its place and purpose, particularly as they respond to the sharp sunlight and forceful topography of Sydney. His design approach, particularly the planning, was rooted in the modern humanism of his early study and travels, together with sensitive but uncompromising forms and materiality, often with stepping outlines following the underlying Sydney sandstone.

Mosman House (top) was comprised of a grid of twelve-foot square units, stepping down the terrain.

Image: Created by Dcmbyl123 (Public Domain)

Kenneth Frank Charles Woolley was born in 1933 and grew up in a California Bungalow in Kingsford, New South Wales . Encouraged by his mother Doris, he showed a talent for art and music, winning honours at the Conservatorium of Music at the age of ten. Upon finishing at Sydney Boys High School (he was very disappointed it had no art classes) he won a traineeship at the NSW Public Works Department that not only paid for his tuition in architecture at the University of Sydney, and an allowance, but also provided practical experience in the summer holidays and required five years of service after graduation. Aided by that practical experience during study, and his prodigious skill in freehand drawings, Woolley graduated in 1955 with the University Medal, two other major awards and, crucially, the Byera Hadley Travelling Scholarship (that paid for overseas travel and study).

Before travelling, Woolley started working full time. Harry Rembert, who was instrumental in the Public Works Department gaining a reputation for excellence, spotted his talent, and gave him the chapel at St Margarets Hospital to design. Perfectly round, sixteen metres in diameter, formed of vertical concrete panels “like barrel staves” with slit windows between, with a ring beam to hold the radiating steel trusses, it was an exquisite first building. And it can tell several stories. Woolley used the round ring beam with articulated trusses at a far grander scale, in the Royal in the Agriculture Showground Exhibition Halls built in 1998 for use during the Olympics. He would return to the ideas, but not necessarily the forms, of earlier works. As a result his work was highly intelligent but less identifiable, and hence less known, than many of his contemporaries. Secondly, his love of architecture and teaching was on display when he graciously guided Sam Marshall in his reworking of the Chapel building 50 years later into an exhibition space for the Object design gallery, after the hospital was decommissioned. And thirdly, and sadly, it was the venue for his private memorial service this month.

As St Margarets entered construction in 1956, Woolley headed on his study tour to Europe. Looking back now we can see the positive influence of the three greats that he always acknowledged: Alvar Aalto, Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. But it is his time working at Chamberlin Powell and Bon (architects of one of brutalism’s most iconic works, Barbican Estate in London) that shows very strongly in the urban buildings that were to come on his return home: Fisher Library at Sydney University (1962) and the State Office Block (1965, now demolished), which were both designed while at the NSW Government Architect’s Office and Sydney Town Hall House (1971-74) and the Wentworth Student Union (1972). The first two were “sheathed” in bronze, whereas the latter two, designed in the practice of Ancher Mortlock and Woolley, are bare concrete, remarkable for their “sensitive brutalism,” if you will excuse the oxymoron. Town Hall House is finished in an acid-washed buff-coloured aggregate that closely approximates the sandstone of the heritage Town Hall proper, which it connects to, an approach followed in several other CBD civic buildings of the time (the 1965 Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board and the 1977 Queens Square Law Courts buildings by McConnel Smith and Johnson) that suggested a “Sydney School” for high rises.

Woolley’s skill with large commissions was established and was to continue in the ABC Radio and Orchestra Centre in Ultimo (1992) and the Garvan Institute of Medical Research (1994). Both showed Woolley’s interest in the clients’ brief as generators of form. The ABC was consolidating its operations from several disparate buildings around Forbes Street in Darlinghurst, where staff interaction was in the street rather than the buildings. The new singular building mimicked that arrangement, with an internal street with activities on either side and on upper level walkways – the “street” being a public space in office hours that now links to the newly opened Goods Line. Finished in sandstone coloured aggregate again, it closely follows the Ultimo street grid, except for the radio studios that crank to the CBD grid to which they face, and broadcast. A similar internal street in the Garvan building, again for interaction, features a seven storey helix stair, based on the idea of DNA geometry as a symbol for that institution.

State Office Block, Phillip Street, Sydney, 1967.

Image: Courtesy State Library New South Wales © Max Dupain & Associates

While there is some consistency in the large works, it is in the mid-scale that Woolley’s diversity of approach and productivity is evident. From ground-hugging and responsive staff and union buildings at Newcastle University, to a wave-shaped Queenscliff Surf Pavilion to the winding Control Tower at Sydney Airport, to the sinuous plan curve of the Park Hyatt hotel under the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Woolley saw it as a badge of honour that the consistency of output could only be gauged in quality, not in repeated forms or even materials.

His only major building overseas, the Australian Embassy in Bangkok, eschews the solidity of the “walled” Sydney urban works for a trabeated architecture supporting a broad shading roof, set in a water-filled garden. The breadth of this extraordinary output is best seen in the book Ken Woolley and Ancher Mortlock & Woolley: Selected and Current Works (Images Publishing, 1999). His work continued right up until his death, when he was working on a number of schemes for concert halls based on his love of music.

It is at the domestic scale that Woolley’s work was at its most inventive and influential – from early on he was interested in the “everyday” home. He won a competition for a low cost exhibition house with Michael Dysart, in 1958. Consequently, both architects were invited to submit designs for a display village of model project houses in Carlingford, in 1961. This led Woolley to fifteen years of work with Pettit and Sevitt, widely regarded as the most innovative of house builders for the aspirational middle class on Sydney’s north shore at the time. White bagged brick, exposed timber posts and beams and split levels (that could adapt a standard plan to the rocky terrain), were the external hallmarks, but it was the clever internal planning, in very small areas, that saw 3500 of Woolley’s designs built.

A Pettit and Sevitt house, designed by Ken Woolley.

Image: Created by Dcmbyl123 (Public Domain)

As good as all this architecture is, the ultimate testament to Woolley’s genius as an architect of creativity is the three houses he designed for himself: built over three decades, each one was radically different to the previous, and each one won the Wilkinson Award, the Australian Institute of Architects New South Wales chapter’s highest honour for house design. All on steep sites, the houses reflected the place and the times. The Palm Beach house (1986) is an airy pavilion sitting on stilts; the urban Paddington House (1980) has complex interwoven curved forms in plan and section, and the first Woolley house in Mosman (1962) is rightly famous for its grid of twelve-foot square units of interlocking spaces stepping down the rock outcrops in multiple levels. It was widely published and bought Woolley recognition at an early age, which enabled him to have a richly diverse career for more than 50 years. It is a sad irony that the highly regarded architectural historian Jennifer Taylor, who used Woolley’s Mosman house as a capstone in her first book An Australian Identity: Houses for Sydney 1953-63, should pass away in the same week as Ken Woolley.

We have lost a great architect.