I labelled this writing file “PP AA” and immediately thought that Paul, master of concision, would have approved. (It’s like that these days: wherever you go, he’s still there, as a guide.)

But back to being concise. When Adrian (Welke, Troppo co-founder) and I first met Paul in Tassie in 1985, as speakers at a student conference, we were there on the strength of having proudly produced little buildings that strove as hard as possible to leave out walls and to exchange enclosed space for the delight of verandahs and decks. It was palpably evident that our nascent Troppo minimalism was no match for Paul’s mini-er platforms of fencing pipe frame and self-spanning curved tin. We did house additions; he achieved house reductions … We had met a guru; we would have to study and follow.

It wasn’t the first time that we had been destined to follow this man. Paul and three friends in their around-Australia, double-decker-bus student epic had already inspired our own kombi van student voyage of regional architectural discovery.

By the 1990s we found ourselves following Paul and Healthabitat to South Australia’s far-northern Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands. There, in the red dust and wavy grass plains, he taught us to make forever tougher, no-nonsense architecture within his carefully considered delivery strategy for what was to become an almost twenty-year rollout of Nganampa Health Council’s step-by-step infrastructure program.

Behind the strategy for building strong lay three great written works that today remain ultimate guides to construction in remote Australia …

Report of the Uwankara Palyanyku Kanyintjaku, “Strategy for Wellbeing” report (1987) by Nganampa Health Council, South Australian Health Commission and Aboriginal Health Organisation of South Australia.

Firstly, the 1987 UPK (Uwankara Palyanyku Kanyintjaku, “Strategy for Wellbeing”) Report, prepared for Yankunytjatjara leader and Nganampa Health Council director Yami Lester by Paul and his soon-to-be Healthabitat co-founders, Dr Paul Torzillo and Stephan Rainow, is a significant work.

Secondly, the principles espoused in the 1993 Healthabitat publication Housing for Health still guide NSW Health’s engagement in improving living conditions in Aboriginal communities.

Thirdly, the 2007 National Indigenous Housing Guide prepared for the Australian Government (for the then Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs) remains the authoritative standard for, in its own words, “planning and development of Indigenous housing in terms of design, construction and maintenance for remote communities.” Its direct user-friendliness is pure Pholeros concision.

Housing for Health: Towards a Healthy Living Environment for Aboriginal Australia (1993) by Paul Pholeros, Stephan Rainow and Paul Torzillo (of Healthabitat).

Throughout these times, on behalf of Indigenous Australia, Paul battled government at state and Commonwealth levels. The article written by Elizabeth Farrelly in The Sydney Morning Herald in February 2016 summarized the Healthabitat story and Paul’s hard yards in remote communities:

“Third-world disease was wrecking lives and prevention was as easy – and as difficult – as plumbing and wiring.

Pholeros developed a suitcase-size testing kit and a protocol that involved training locals on day one, both to do the work and to train others. The cost? An average of $7500 per house.

With a weary patience, Pholeros insisted on dispelling three myths. One, that the problem is too large, too hard; situation hopeless. Two, ‘you’ve heard it all your lives,’ that aboriginal people trash houses. Three, that ‘aboriginal people won’t work.’

‘Of course it’s solvable,’ he said. Ninety-one percent of the damage to houses is through faulty construction or lack of maintenance. As to laziness? ‘Nonsense.’ By 2011, Healthabitat had 831 local indigenous people employed as builders, planners, project managers, tradies and database operators.”

It wasn’t just that Paul had a message for us all. He knew how to tell it, to inspire, without complication or conceit. Pithy data became an arrow at a bullseye, a cynical comment a call to arms, a quickly sketched cartoon replaced paragraphs of explanation, a silence hung for your own realization. Paul’s remarkable ability to distil the complex, to sum up the bleeding obvious, was an art. An art that enthralled – and changed forever – so many students and practitioners, so many bureaucrats and punters (as he’d lovingly call the users of architecture), here and overseas.

Paul’s 2013 TED talk on Housing for Health and its nexus to reducing poverty, delivered in his calm, lucid and wry style, has had well over one million views. The talk, as ever, was accompanied by his pen – with diagrams and cartoons adding poignancy or entirely replacing words.

The art of drawing, of distilling one’s thinking through the pen, is an architect’s supposed skill and Paul was a master. My favourite, which he smoothed through talks in the 1990s, was The Great Diagonal, in which he reduced Australia, from Broome to Sydney, to a single line cross-section, with a nipple for Uluru, a pinch for the Great Dividing Range and a flourish of Opera House at its foot. The section sets up the space that echoes our whitefella lack of understanding of this wide continent and its original people who are still so connected to Country – all of it, all of that flatness. For us insecure coastal dwellers it might echo the emptiness of modern cultural and spiritual purpose.

In 1993 Paul joined with friends Glenn Murcutt, Rick Leplastrier and Peter Stutchbury to respond to Paul Keating’s request for submissions for the National Museum of Australia in Canberra. The team’s handwritten submission was classic Pholeros – no large gesture on the shores of Lake Burley Griffin, rather a string of small museums, like beads of a necklace lacing the continent. Museums on Country would not only enable a discovery of Australia, they would also be a means of repatriating artefacts, a way for its many peoples to own and tell their stories in place, empowering all.

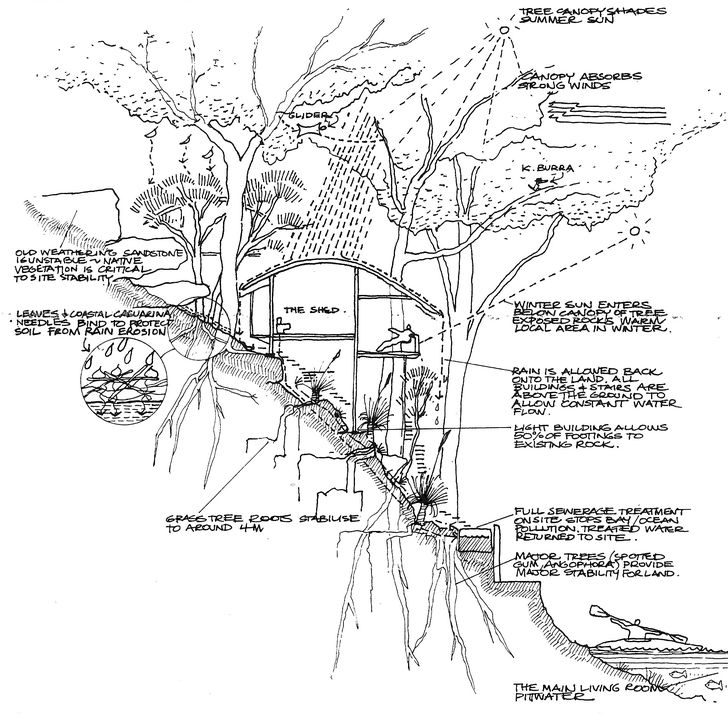

A sectional drawing by Paul Pholeros of his design for the partly fabric-clad dwelling at Bilgola Plateau.

Paul found respite from his journeys in a small bower perched on Bilgola Plateau in New South Wales above his cherished Pittwater. This fine, partly fabric-clad structure shivers with the tempests and basks in the sun and breeze. It was a sacred place that he and his partner Sandra Meihubers shared. From here he also ran his practice and in between times, on a deck in the treetops, he’d be found huddled over a hibachi, charcoal-cooking fish for friends.

Paul’s formal achievements are significant. In the spirit of PP concision we can list: Bachelor of Science Architecture (1974) and Bachelor of Architecture (Hons 1, 1976), University of Sydney; Paul Pholeros Architects, 1984 on; director, Healthabitat, 1985–2016; Royal Australian Institute of Architects President’s Award, 1994; adjunct professor of Architecture, University of Sydney; Member of the Order of Australia (AM), 2007, in recognition of his persistence and outstanding service to the health and wellbeing of the Indigenous population of Australia and the Torres Strait Islands; vice-chair, Emergency Architects Australia; member, Prime Minister’s National Policy Commission on Remote Indigenous Housing, 2007–2009; Australian Institute of Architects Leadership in Sustainability Prize (Healthabitat), 2011; World Habitat Award (Healthabitat), United Nations Habitat and Building and Social Housing Foundation, 2011; and Rockefeller Foundation, Bellagio Residency Award, Italy, 2011.

Torzillo summarizes this achievement list simply: “[He] had an incredible mind and dynamism that he used consistently over thirty years to improve the living standards of people living in poverty. Through the sheer force of his personality he was able to inspire a generation of people to work to improve the living environment of disadvantaged communities. He was able to generate real momentum in the international community.”

Today, HH (thx Paul) programs continue in Johannesburg (Adrian now following there), Nepal, Bangladesh and Ethiopia, with Healthabitat O/S directing their future. In the end, it wasn’t just what this big fellow did, it was the gentle way he drew us all into his own ever-expanding understanding, opening doors to ways of thinking that were full of consideration and compassion and compelling, enduring logic.

As one post on Paul’s passing on the Healthabitat website reads: “If I could thank Paul now, it would be for the glimpse into the other Australia which lies on our doorsteps, but which so few of us venture past. I would thank Paul for providing an insight into that great space and the people to [whom] it has been home … for all those thousands of years. In a world with so much static, Paul had this sense of absolute clarity, calmness and purpose.”

Paul, you have left us a songline; we will continue to sing it, steadfastly.

Source

People

Published online: 22 Dec 2016

Words:

Phil Harris

Images:

Courtesy Sandra Meihubers

Issue

Architecture Australia, November 2016