The recent talk (February 2013) in Sydney by Valerio Olgiati, part of the Australian Institute of Architects International Speaker Series, presented an opportunity to consider the possibility of architecture to hold meaning, and the nature of that hold.

I have not visited any of Olgiati’s projects, but am familiar with the various texts on the architect and enjoyed his recent lecture, given after the architect spent a full month travelling around this continent, unusual for someone of such profile.

I first came across Olgiati when I was encouraged to visit an exhibition of his work at the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo. Models of his projects were presented at the scale 1:33, precisely made white forms with extraneous detail removed, Olgiati’s compact forms pulled apart to reveal the internal complexity within apparently simple volumes.

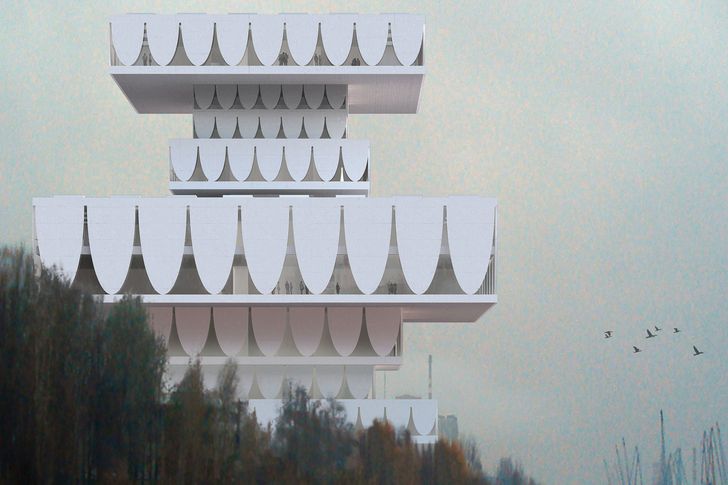

Proposed pavilion by Valerio Olgiati on the Caumasee, in Flims, Switzerland.

Image: Courtesy Meyer Dudesek Architekte

The consistent scale meant that the models of smaller houses were indeed very small, about 150 mm high, whereas some of the larger projects were represented by enormous models, the proposal for a tower in Lima reaching the ceiling.

David Neustein’s insightful article Valerio Olgiati and the cult of architecture, recently published on ArchitectureAU, serves as further context and in large part the stimulus for this article. There is a quality of excellence in Olgiati’s work that I think has not been adequately acknowledged, and none of the other elements – Olgiati’s following, reputation, even the sense of “myth” built around his practice – would exist if the work were not of an extraordinarily high standard.

Contrary to the suggestion that his work is “more or less like any other” minimalist Swiss architect, I would suggest that the presence of myth, within the core content of the work as opposed to that surrounding the architect’s work, is what distinguishes him from his contemporaries. The precision of his work is only a tool to heighten less rational qualities, evoking myth and often having the archaic quality of a ruin.

Pure architecture and newness

As referenced in Neustein’s article, Olgiati’s stated aim is to create architecture that is “not symbolic and not historical” but “purely architectural.” The question of whether architecture is “capable of negating or transcending any symbolic and historical interpretation” is central. The setting of this inevitably unreachable goal is the source of tension in his work and worthy of further examination.

Olgiati can be loosely placed within an intellectual tradition centred on Northern Italy and Switzerland, within or under the shadow of great mountains that divide the landform of Europe and create a sense of removal from the major centres, both by distance and altitude.

Paul Klee, Peter Zumthor, Aldo Rossi and Carl Jung all spent significant amounts of time in the region and perhaps offer complementary (although of differing significance) components of an approach to thought that is both super-rational and yet beyond the rational, using precision of various types to apprehend something far less explicit.

Precision is not the point, so to speak, but it creates a sharp and defined threshold over which to step into something beyond the rational, as ambiguous as an unarticulated sense of longing.

In my own thought process I have recently settled on the term of the “loss of history” to give words to this sense of longing – an idea that at some level what we have made is futile and will inevitably pass. On reading a summary of Rossi, I was comforted by his reference to this sense of longing, whereby he uses Jung’s term of “analogical thought” to describe a sense of non-verbal longing.

Olgiati has previously stated his goal as producing “newness.” He gives the example of Mayan temples as “non-referential” architecture, unable to be explained by their origins and hence a “pure invention.” Olgiati compares this to the temples of Angkor Wat, clearly abstractions of mountain forms, in particular Mount Meru from Hindu mythology. Olgiati is “fascinated by a society that is able to construct an artifact that is not an abstraction.”

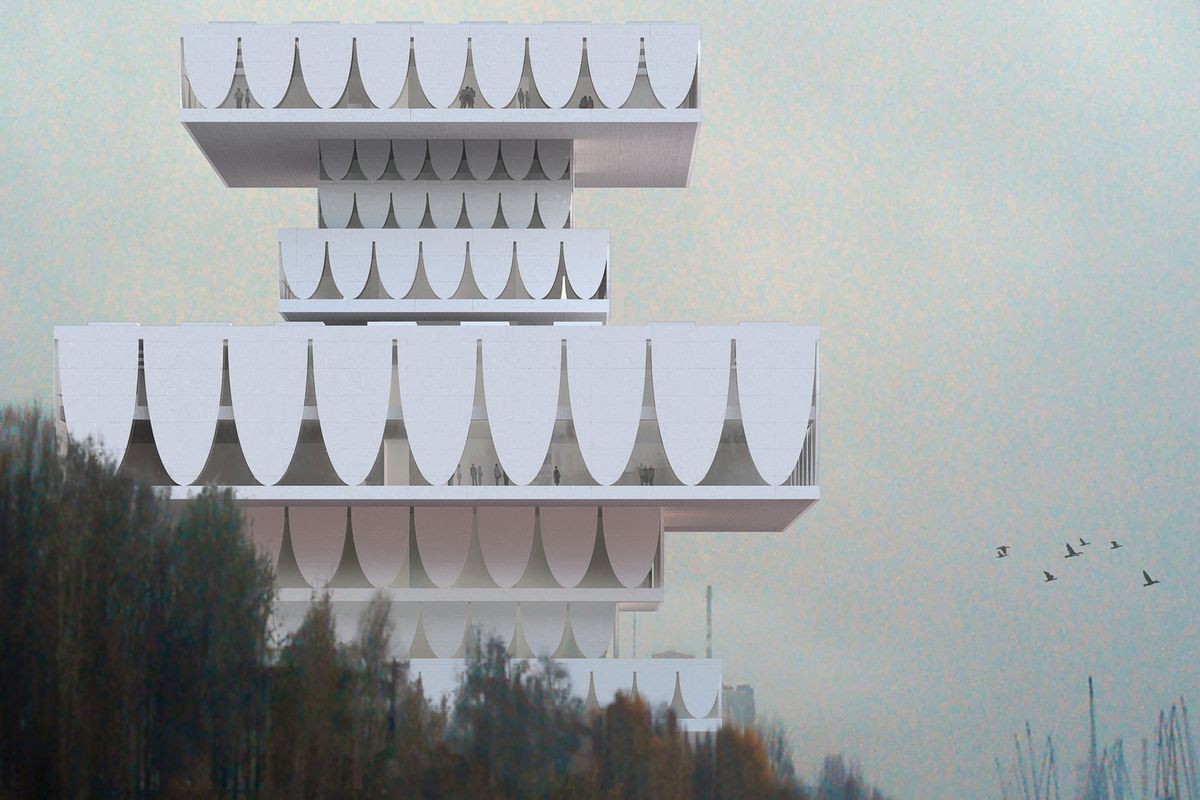

Valerio Olgiati’s Perm Museum XXI, Russia.

Image: Total Real AG

To my reading, Olgiati’s buildings seem charged with meaning of some form, difficult to place, but nonetheless present. The Perm Museum of Contemporary Art, in particular, seems pulled out of mythology (of the ancient sort, not the sort an architect might seek to cultivate), yet its origin cannot be placed, akin to Olgiati’s description of the Mayan temple. He himself states that he is not seeking any meaning and indeed does not “believe in anything.”

By skilfully charging a project with obtuse meaning, or at least a sense that there should be a meaning, yet not claiming it, Olgiati’s buildings seem capable of holding many meanings. They become a fissure in our rational desire to narrowly interpret meaning.

That is probably the source of the myth that has built around the architect; by not claiming meaning he opens a door to the possibility of many meanings, and onto this the “audience” can project a longing. Whilst I do not personally think there is much in architecture to pin our deeper hopes on, I can sense that Olgiati’s works can respond to a longing, perhaps for the archaic.

At the talk, Angelo Candalepas’s question to Olgiati – “do you design spaces for spirituality or enjoyment” – was precisely the right question, but impossible for Olgiati to answer. His work has an ambiguity that arises from the integration of perhaps contradictory elements and Olgiati’s response of “feigned confusion” was maybe an attempt to maintain an ambiguity that has been hard-won and built over time.

The question was possibly stimulated by Olgiati’s proposal for his own house in Portugal, which integrated many spatial meanings; the remnant presence of a cruciform, here employed to heighten leisure, the living room and lounge, reminiscent of Utzon’s Can Lis, occupying a position of centrality and enjoying an axial view of the courtyard, the deferential position of the kitchen to the corner of the courtyard and the simplicity of the corridor device, creating gradations of and a passage of time where one can not see an ending.

Rigour and organism

There is a rigour to each of the architect’s projects, both at an autonomous intellectual level and at the practical level of the architectural detail. Clear-minded decisions about materiality seem to be made early, and contain understanding that anticipates the difficulties of refined expression – the placement of framing outside the wall avoiding the issue of constructional tolerance is a prime example, also granting the spaces a type of material directness.

It is hard to find a glitch or anything inessential, yet the buildings are not reductive. They are, to use Olgiati’s term, “organisms,” like the body, free of inessential elements.

Valerio Olgiati’s Plantahof Auditorium, Switzerland.

Image: Javier Miguel Verme via

The “unities” that Olgiati strives for in the Plantahof Auditorium are not compromised by the presence of the cross-beam and anchoring T-beam. Rather, these things make overt a more complex type of unity, where a composition of structural elements works as a complete system that support an initial decision to achieve a consistency of thickness for walls under differing loads. It is a rigorous system whereby one decision impacts others and pragmatically generates architectural content.

Degree of difficulty

The creation of precise buildings is difficult in itself. The creation of ambiguity as a receptacle of longing is more difficult still. Olgiati has achieved both and has gained wide recognition for this. We can surely appreciate the work without enlisting in the “cult of Olgiati.”

I take recent criticism of Olgiati’s Sydney appearance as a timely reflection that architecture can turn inwards and lose social purpose. This is one of the challenges of practice, the necessary autonomy of architectural thought in creating excellence, yet the fact is that such an approach sits only a few steps away from irrelevance.