Healthcare facilities are characterized by constraint, required to organize complex systems, services, movements and processes. Disrupting existing models of practice necessitates that we find new ways of responding to old problems. Plenary Health led the project team that delivered this challenging project and asked a bold question: what happens when you invite a healthcare newcomer into your design team? The Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre (VCCC) was delivered by a consortium that included two architectural practices with strong track records in the delivery of healthcare facilities, Silver Thomas Hanley (also responsible for Monash Children’s Hospital, Bendigo Hospital and Box Hill Hospital) and DesignInc (Bio21 Institute, Royal Adelaide Hospital and Royal Women’s Hospital). The newcomer was McBride Charles Ryan (MCR), a firm known for projects that border the spectacular and for whom conventions exist to be challenged. MCR’s role within the project was to complement the expertise of Silver Thomas Hanley and DesignInc by defining the architectural intentions of the project, controlling the expression of the building and providing a response appropriate to the ambition of this endeavour.

VCCC occupies a junction between the Melbourne CBD, The University of Melbourne and research and teaching hospitals.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Air bridges provide direct links from the VCCC to the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

Image: Peter Bennetts

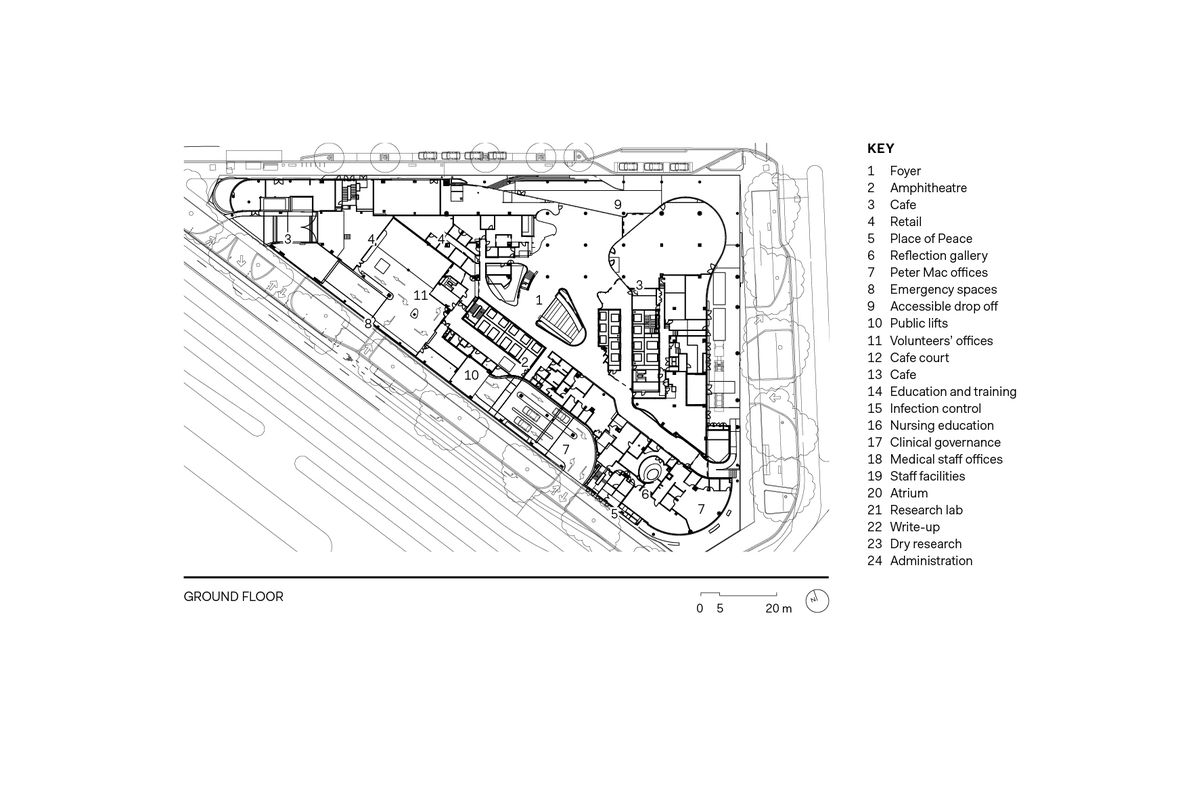

We’ve all seen the numbers; they’ve been cited across multiple media platforms: a floor area of 130,000 square metres – of which more than 20,000 square metres is devoted to research, housing up to 1,200 researchers – ninety-six inpatient beds, space to deliver same-day treatment for up to 110 outpatients, six operating theatres (with future capacity for eight) and eight radiation therapy bunkers. We elect to join this continuous citation not because the numbers impress us but because they barely hint at the complex functional program of this facility. Without them it is easy to lose sight of the magnitude of this architectural achievement. But this is no warehouse. It’s a building about people, about delivering the care they require and establishing a relationship with the city. The VCCC occupies a junction between the Melbourne CBD, The University of Melbourne and the research and teaching hospitals to which it is intimately tied. These buildings share a formidable history of groundbreaking medical discoveries and, architecturally, set new standards in global health design. The VCCC, as the latest addition to this cluster, stands as the gateway to the Melbourne Biomedical Precinct: a collection encompassing more than twenty-five health service, research and academic partners within a three-kilometre radius. It confidently fulfils the urban requirements of its prominent landmark site, orientating visitors to this precinct and establishing an important urban vista on a site that has been fragmented for many years.

The design of the VCCC rejects typical associations with the institutional. The architects wanted it to be instantly recognizable with a “dynamic, fluid and organic” form.

Image: Peter Bennetts

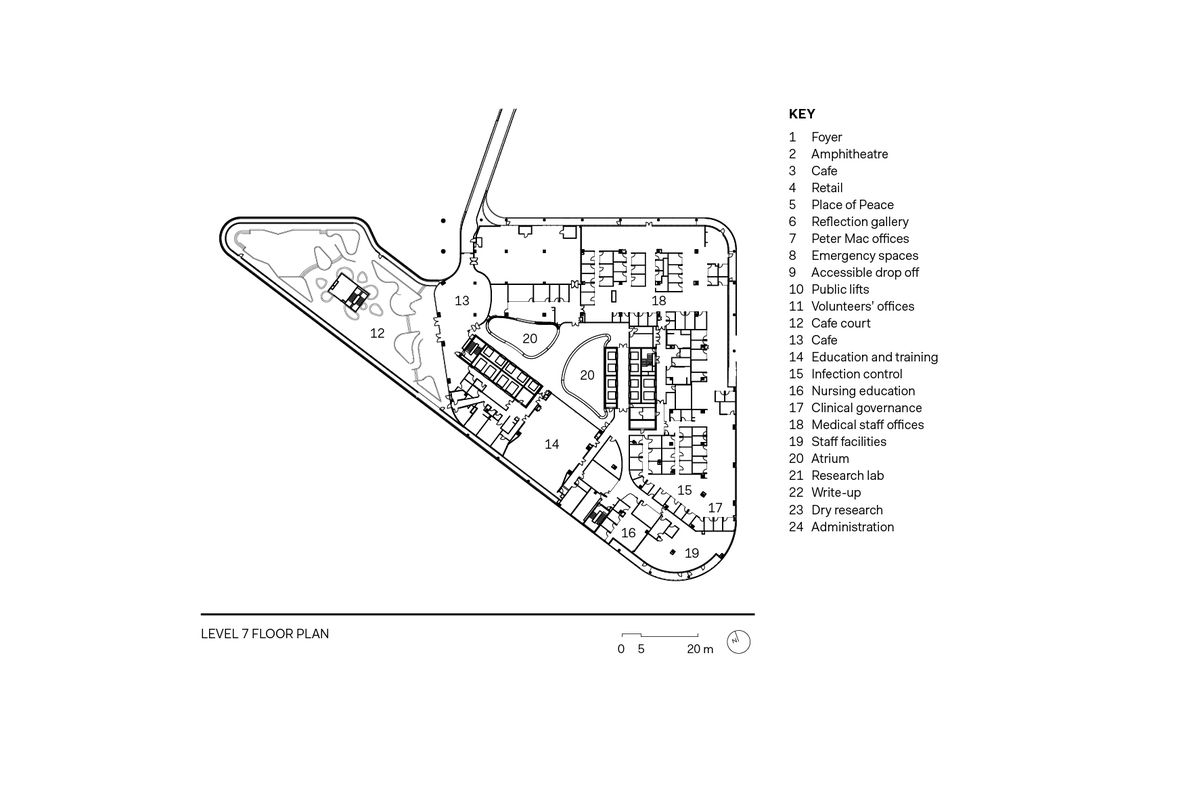

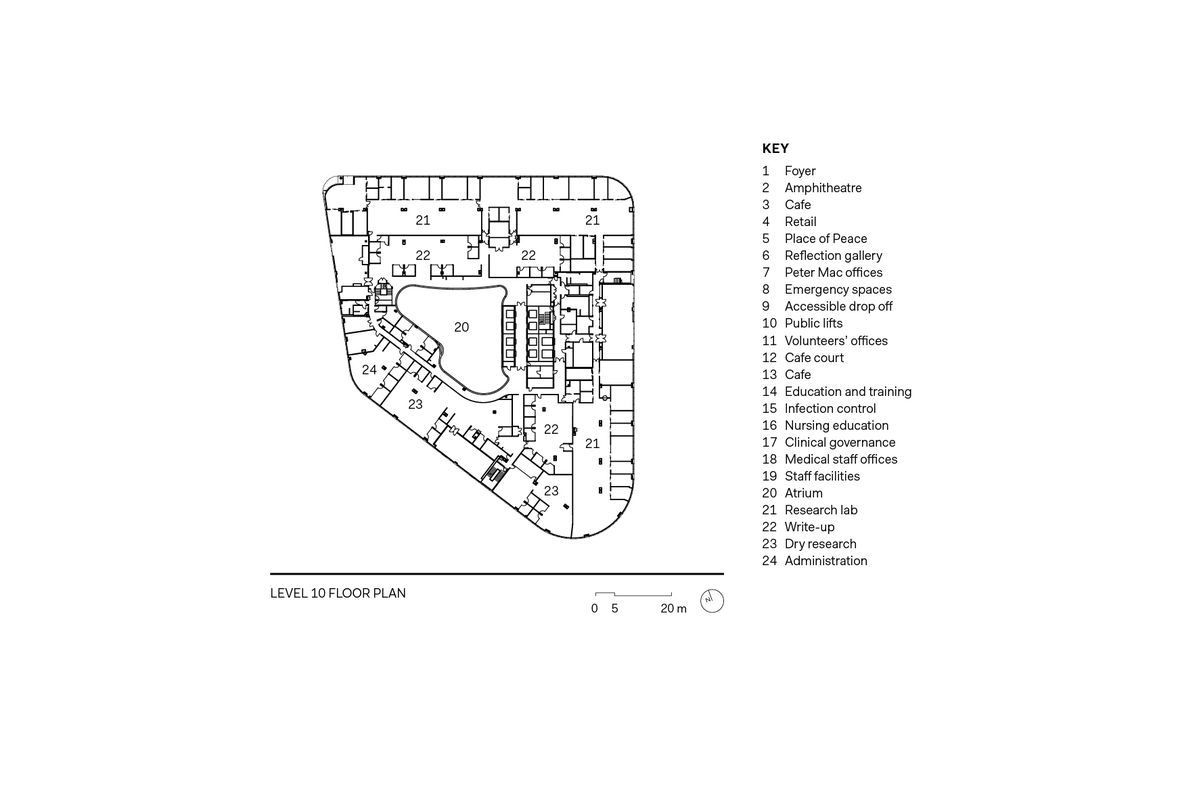

Clinical functions are accommodated within the lower half of the building. The first floor houses the Wellness Centre, the Sony Foundation You Can Youth Cancer Centre and accommodation for rural patients and their families. Allied health, the pharmacy and ambulatory care occur on level two and same-day medical and chemotherapy on level three, alongside a 32-bed inpatient unit. Pathology is located on level four alongside data and communications. Imaging is spread over levels four and five with a recovery suite and 32-bed inpatient unit located on level five. Level six accommodates a further 32-bed inpatient unit and the operating theatres; it gives access to an air bridge connecting the ICU department of the Royal Melbourne Hospital (extended and updated as part of the wider project) to these new surgical theatres. While floors eight to fourteen accommodate research facilities – wet and dry labs, offices and facilities for research staff – the seventh floor is where clinical and research functions converge, allowing for a confluence of educational space with public space. This floor includes a cafe, a publicly accessible rooftop garden, lecture theatres, an internal civic space (where conference functions can be held) and a publicly accessible sky bridge connecting to the Royal Melbourne’s ICU department. The six levels below ground contain parking, ambulance bays, kitchens, plant rooms and the radiation bunkers. There is a discussion we could have about how the building functions. How well it responds to the concept of “patient-centred care” through its provision of the dedicated Wellness Centre, or the cafes and rooftop gardens that afford spaces for friends and family to play a role in the treatment process. We could talk about how important these provisions are, how they provide crucial opportunities to maintain the sense of normality that cancer researchers agree contributes to a patient’s ability to cope with the stress and uncertainty associated with this disease. We could also talk about the quality of the consultation spaces and inpatient rooms, the expansive glazing, natural light and city views. But much of this is best practice. We’d expect nothing less from a design team that included Silver Thomas Hanley, DesignInc and MCR. Instead, let’s talk about the wider contribution of this building to the development of the healthcare typology.

VCCC houses ninety-six inpatient beds and space to accommodate up to 110 outpatients for same-day treatment.

Image: Peter Bennetts

While the emergent field of evidence-based design attempts to measure the relationship between architecture and wellbeing, the methods we have for collecting this evidence are not yet as sophisticated as the environments we are trying to measure. Great architecture is not about plugging in a set of ideal specifications (light levels or corridor widths), but relies on a carefully crafted convergence of materials, light and the sequencing of spatial volumes. It accommodates a degree of subjectivity in its reading and assumes that a particular architectural response might evoke past experiences and associations or, in the case of the VCCC, reject all associations with the institutional. While the contribution of good architecture to wellbeing remains challenging to measure, this does not render its contribution any less important. The brief demanded a building that would welcome patients, a tranquil space that would evoke optimism and inspire hope, and a facility capable of becoming one of the top ten cancer research centres in the world. Anecdotal evidence – accounts from staff, patients and visitors – suggests that the architectural team nailed it. There is a collective sense that people are inspired and comforted by this environment, while staff suggest that the building is already acting as a change agent for better practices across the organization.

While it isn’t all about appearances, there is little point denying that the messages medical facilities communicate are important. A former patient of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre (now incorporated into the VCCC) commented that the way the new building “stands confidently on the street, looking all space aged” reassured him that we were leaping forward in our battle against this disease. The architects wanted the building to be distinct, instantly recognizable. They use the words “dynamic, fluid and organic” in describing the architectural intent. The VCCC might stand confidently but it does not stand still; the form – a spiral, emblematic of progress and hope – speaks of constant motion, of continuing to strive, to remain agile and responsive to new challenges and possibilities. The tendrils that reach across the facade provide a reference to the convergence and exchange of ideas in unlocking new understandings in the treatment of cancer. There is poetry in the colour purple also. Traditionally associated with royalty, it became widely accessible in 1856 following an accidental discovery by the chemist William Henry Perkin. While attempting to synthesize quinine (used for the treatment of malaria), Perkin stumbled upon a method for mass- producing purple dye. This association with the history of organic chemistry provides a fitting reference to the unanticipated benefits of research.

Materials are rich and detailed yet restraint is shown in the monochromatic palette, which reflects the abundant daylight.

Image: Peter Bennetts

The prominence of the research program continues inside. A key aspiration of the brief was for the architecture to facilitate translational research – to speed up the transfer of new knowledge from the lab to the bedside. Lift access to the research floors is placed front and centre within the entrance lobby, a deliberate strategy to enable patients and researchers to “rub shoulders.” The building’s organization around the central atrium echoes a wider preference for this spatial type in healthcare, clinical and research settings, due to its facilitation of incidental meetings between researchers and clinicians that might result in biomedical advances. The architects hope that patients will be reassured by the presence of researchers and by the knowledge that they are striving daily to improve cancer care, while research efforts will in turn be bolstered by direct contact with the patients for whom this research makes a personal difference.

The spiral, emblematic of progress, is used throughout the building to evoke optimism and inspire hope.

Image: Peter Bennetts

The porosity provided by the VCCC, with its deep portico, glazed atrium and integration of semipublic spaces at ground level (cafes and retail outlets), provides a stark contrast to the relative impermeability of its neighbours. This building recognizes that an entrance is so much more than a threshold; it conveys implicit instructions for our behaviour and sets our expectations for what is to follow. There is a quiet fortitude to the Welcome Hall and the architects were surprised to discover that there is a certain hush when you enter this building, a sort of unexpected reverence. Yet they speak of wanting a space that is awe-inspiring but not overwhelming, “like a modern Gothic cathedral.” In paediatric hospital design, distraction is a strategy commonly employed – through the inclusion of artworks and gardens – to transport the imagination from the pain and anxiety associated with illness. The VCCC’s architectural response challenges us to ask why distraction should be any less relevant in adult settings, particularly those for oncology patients. Materials are rich but restrained, punctuated by moments of intense, monochromatic detail. The striking geometric forms are softened by sweeping curvatures, with daylight spilling in from all directions. It is uplifting, momentarily transcendent. But this is also a no-nonsense interior, as if the architecture itself is somehow aware of the gravity of its purpose and quietly respectful of the battles that will be won and lost within its walls.

As with any architecture that speaks of effortless restraint, you require an awareness of construction techniques to appreciate the precise, complex and digitally enabled processes that created this physical space. At the 2016 Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA) conference, MCR’s Drew Williamson expounded on the firm’s ongoing experiments with construction and fabrication, offering some insight into how such complexity was able to be achieved in such a large public building – and a healthcare facility at that. Williamson explained how elements that were nonconventional in their construction were taken off the critical path to allow the necessary processes of experimentation and refinement to occur at their own pace, without causing delays to project completion. Collaborative engagement with suppliers, manufacturers and craftspeople, employing digital technology to its best advantage and formulating new paradigms for contract tender and procurement thus become the critical backstory for understanding this building. The dedication of the wider project team to maintaining these elements through a robust value engineering process, via an innovative procurement strategy and a willingness to take on the risks associated with these nonstandard elements, is a feat worthy of commendation. There is fitting poetics in the resilience of these elements and in the level of architectural, structural and contractual innovation they were born from. Might they subconsciously inspire the medical innovations we hope for?

The Flemington Road elevation of the VCCC establishes an important urban vista on a site that was previously fragmented.

Image: Peter Bennetts

The VCCC ties into a wider movement that owes a debt of gratitude to Maggie Keswick Jencks, founder of the Maggie’s [cancer] Centres (UK). Each designed by a celebrated architect, these recast the world’s expectations of what a patient-centred healthcare architecture could look and feel like. Of course, the Maggie’s Centres are auxiliary facilities; they provide information, advice and psychological support to cancer patients and are light on the demands of technology, necessary efficiencies of movement and concerns about infection control. To bring this sensitivity into a clinical and research setting is a far more difficult proposition. In its deliberate and consistent effort to erase all trace of the architectural cues we associate with institutional interiors, the VCCC has boldly blazed this trail for others to follow. The VCCC does much to advance the field in disrupting our expectations of contemporary healthcare facilities. To borrow the words of James Patten, this is a building that might just result in “a dramatic and disruptive impact on the world.” We keenly await the evidence.

Credits

- Project

- Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre

- Architect

- Silver Thomas Hanley

- Architect

- McBride Charles Ryan

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Architect

- DesignInc

Australia

- Consultants

-

Builder

Grocon PCL joint venture

Project sponsor, equiry investor & financial arranger Plenary Group

Services provider Honeywell

- Site Details

-

Location

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Health

Type Hospitals

Source

Project

Published online: 3 Jul 2017

Words:

Rebecca McLaughlan,

Alan Pert

Images:

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2017