West Gate Bridge Memorial Park proposal by ARM.

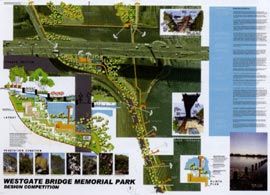

Entry by Mark McWha Landscape Architect.

Proposal by Black Kosloff Knott, with Urban Initiatives, Arup, Barry Webb and Associates and Clare Firth-Smith.

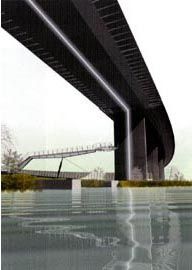

Proposal by Black Kosloff Knott, with Urban Initiatives, Arup, Barry Webb and Associates and Clare Firth-Smith.

Entry by Coombes Consulting in association with Arup and Mark Stoner.

Proposal by Team Eleven: Anthony Styant-Browne, Contour Design, Ecology Australia, The Flaming Beacon, Greg Johns, Julia Jame Design, Kevin Murray, Lambert and Rehbein, Magian Design Studio, Rick Amor and Ros Bandt.

Proposal by Aspect Melbourne, Landscape Architects, in association with Charles Anderson, artist, Kerstin Thompson Architects, Arup, Brett Lane & Associates Ecosystems and Martin Butcher Lighting Design.

WE ALL DIE. More people die annually in Victoria on the road system, of which the West Gate Bridge is just one small span, than did in the accident that occurred during its construction in 1970. The desire to commemorate the thirty-five men who died in this accident through a public memorial park below the bridge comes out of the recognition that these deaths have larger resonances in the community. What occurred in 1970, and in 1895 when six men died during the construction of the nearby sewer tunnel beneath the Yarra, symbolizes the unequal risk of labouring over white collar work. These were unjust deaths.Workers, and the engineer whose faulty calculations were blamed for the bridge collapse, died as a result of financial ambition, competing interest groups with dispersed responsibility, delays and indecision and poor management. They died in the cause of improving the city.We could refer to notions such as “collective memory and mourning” and “historical trauma” but these are, as Noa Gedi and Yigal Elam argue, notions that “can be justified only on a metaphorical level”.1 How, then, are we meant to consider the transfer of trauma deriving from a particular event down generations or to those who didn’t experience it and were not personally bereaved? The site itself is apparently not enough to effectively address this wider trauma, despite it retaining some of the debris from the accident and already housing two monuments with plaques bearing the names of the dead from both accidents. Something more is wanted, but what?

Ours is an age preoccupied with the material production of memorials and historic sites – attempts in a secular world to derive meaning out of senseless events. The design competition brief for the West Gate Bridge Memorial Park was prepared by Major Parks Victoria at the behest of the West Gate Bridge Memorial Park Association. It asks for a design that functions as the purveyor of a clear message – to honour the notion of work and to remind the visitor of the price paid for unsafe work practices. Additionally, the brief asks for a design that bears witness to and accompanies the treacherous ongoing process of mourning. This second function, of commemoration, suggests a quieter architecture inviting and receiving unstable meanings. The desire is for a memorial park that is simultaneously didactic and enigmatic, transmitter and receptacle. The six shortlisted entries tend to assign different elements in the park to either ambition, leading to fragmented solutions, or emphasise one function over the other, achieving formal coherence at the expense of the other function. One of the submissions, by Mark McWha, seems not to deal with the memorial component at all but concentrates on another component of the brief, the conservation of the Backwash wetland.

The entry by Ashton Raggatt McDougall most clearly demonstrates the expository approach. Elements in the design correspond quantitatively to the event. A raised concrete plinth records the footprint of the fallen bridge. On to this are marked red and yellow rectangles for each of the 35 who died in the bridge accident and 6 sepia-toned plots for the dead sewer tunnel workers. Paint colours to be applied to that part of the bridge where the failure occurred are taken from work safety vests and elsewhere the aesthetic is derived from road signage, traffic infrastructure and movement.

Architecture is here conceived as a kind of informational text, a translation of data into the visual realm, continuous with and augmented by literal text. Written text, a quote by Brecht taken from the Spotswood Sewer victims’ memorial, is given the job of conveying emotional content and is applied in huge scale to one of the columns of the bridge. The project is formally cohesive and immediately apprehensible, but strident.

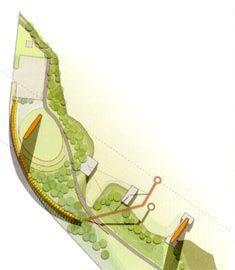

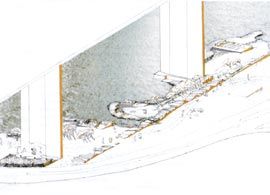

Black Kosloff Knott’s proposal is predicated on replicating the experience of journey through a set of processional walkways and ramps leading to a circular viewing platform cantilevered over the river. The underside of the section of the bridge that collapsed is illuminated by an austere strip of fluorescent lighting. The disposition of architectural forms and materials is intended to promote contemplation of the fragility and unpredictability of life. Where ARM’s proposal uses text to hint at the larger questions around the site, BKK use architecture to suggest the general and resort to inscribed text to recall the specific event. In both cases the supplementary inclusion of text seems to indicate a lack of confidence in architecture’s capacity to evoke or interpret.

The proposal by Coomes Consulting is comparatively modest, consisting primarily of the addition of thirty-five person-sized columns formally aligned along an avenue of honour that stretches across areas of both land and water. There are six more columns closer to the sewer tunnel. These are to be individually sculpted by Mark Stoner and lit at night. Additional boardwalks on the site are arranged to form a central void space.

Emptiness and absence are powerful concepts, but against the scale of the bridge and the river the clearings here would not register. The project successfully integrates ecological ambitions with the design of architectural and sculptural elements.

The team headed by architect Antony Styant-Browne and including a poet, sculptor, painter, botanist and multimedia designer in addition to landscape architects, lighting and engineering consultants, hints at the potential for a landscape solution to be richly evocative. The design screens noise pollution from traffic as do other entries, but it also introduces the whispering of allocasuarinas and audio recordings of poetry and statements about the accident. Visually it is a fragmented composition that embroiders existing elements of the site. The concrete footings used in construction are designated as platforms for contemplation and embellished with text, lighting and sound. The members of the bridge that collapsed are identified with overscaled safety marking below and above with thirty-five commemorative stelae spaced equidistantly from pylon 11 to 12. However, in pursuing a multi-layered and multi-media response a coherent identity for the site has been sacrificed.

The proposal by Aspect Landscape Architects, with artist Charles Anderson and Kerstin Thompson Architects, integrates sound, sculptural form and ecology through the imposition of three unifying themes. The theme of “ecology” is carried out in planting and regrading and satisfies the brief requirement for conservation of the foreshore environment.

The author’s claim that this intervention also relates to the ecology of workers seems disingenuous and unnecessary given the power of the other two themes. The largest element, “The Flange”, aims to recall the catastrophic accident through replicating the collapsed span in length and width. Structural failure is conveyed through its buckled and broken form. A visual and acoustic interpretive frieze is set in The Flange. Recordings related to the accident are played at 11:50 am, the time of the collapse. The other theme, “Home”, examines the relationship between public trauma and private mourning through three sculptural elements placed on the existing concrete platforms. Two of these connote domestic events such as dining and sitting in the abstracted form of places for gathering and contemplation. A third, intended to convey “dreaming”, is a literal representation of bedroom furniture with rumpled sheets whose occupant is forever absent. The insertion of the domestic into the public realm could be uncanny and unsettling, as in the sculptures of Rachel Whiteread, but it might equally falter towards the kitsch. Nevertheless, the conjunction of industrial infrastructure with the home in scale and association in this entry is the most ambitious response to the memorial brief. It reaches towards the fuller meaning of nostalgia, with its roots in the Greek nostos for return, and algos, pain. The universality of home means that this design could function equally well for the many families and friends of unnamed people who have suicided from the bridge.

At the time of writing, a winner is yet to be announced following the exhibition of the six entries in March at the Scienceworks Museum – despite the proposal that the project would be completed by the anniversary of the accident in October this year. Given the complexity of the brief and the difficulty of integrating commemorative and interpretative aims, it is perhaps unsurprising if the decision has been difficult. In addition, the confirmed construction budget of $750,000 appears inadequate to achieve any of the entries, or indeed the ambitions as set out in the brief prepared by Major Projects Victoria. It is a project worthy of greater investment. A considerable and invisible investment has been made in unpaid time and resources spent by the teams of designers and consultants in the preparation of what are, despite my criticisms, impressive and thorough presentations.

All are serious and considered entries. The professionals involved may not have risked their lives, but the phrase “labor in vain” is probably not far from their minds.

SANDRA KAJI-O’GRADY IS A SENIOR LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE