The river elevation. The architects designed the new building as an insertion into the story of the river landscape, with tectonics developed from the river’s “living” qualities. Image: Brett Boardman

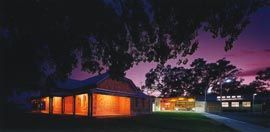

The new accommodation and medical services wing seen across the Barka, as the Darling River is known to the Barkinji people for whom it is culturally and spiritually significant. Image: Brett Boardman

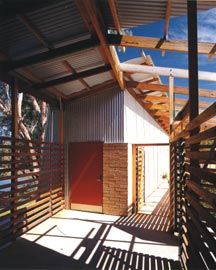

Front entrance, with the original hospital in front and the new building beyond. Image: Brett Boardman

The existing hospital building, an example of a nineteenth century cottage hospital, with one of the two mature fig trees fronting the site. Designed by Cyril Blacket and built in 1879, the heritage building has been refurbished to provide primary and community health services. Image: Brett Boardman

Looking along the ambulance bay towards the link connecting the new and old buildings and the main reception. Image: Brett Boardman

Patient exit from the accommodation and ramp to the patient courtyard. Image: Brett Boardman

View along the patient verandah, showing the relationship between the accommodation, the verandah and the river landscape. Image: Brett Boardman

Detail of the ambulance bay roof. Image: Brett Boardman

Sunshading to the windows along the river side of the medical services wing. Image: Brett Boardman

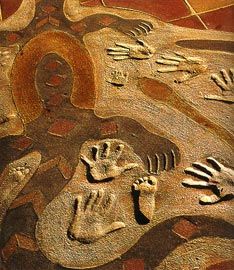

Artwork by Badger Bates, a local Aboriginal designer, with input from the community, on the pedestrian footpath leading from Ross Street to the ambulance bay and main reception. Image: Brett Boardman

Shadows on the locally made stabilised earth brick. Image: Brett Boardman

The river elevation, with the staff resources verandah in the centre and the patient verandah in the foreground. Image: Brett Boardman

The mourning courtyard and entry to the mortuary waiting room. Image: Brett Boardman

Looking towards the mortuary from the link between the mortuary and medical services. Image: Brett Boardman

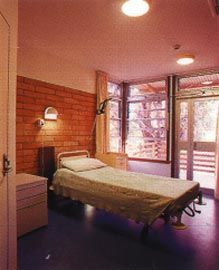

Patient bedroom with view across the verandah to the river. Image: Brett Boardman

Looking east along the circulation spine in the new wing toward the main entry and staff station. Image: Brett Boardman

Internal view of the link between the new and old buildings. Image: Brett Boardman

Places of memory. The river Darling was made by Ngatji – an ancestral serpent, who wriggled its course while travelling across the land. Its name is Barka, and the people of Wilcannia are Barkinji: “river-people”. Barka remains a resource of spiritual and physical sustenance; a place of recreation and ceremony; a refuge from the township, mission or station; a marker of the seasons; a gauge of the health of country; and a link in the intricately woven narratives of other river stories, and other river peoples.

In 1878, Cyril Blacket won a competition to build a hospital in Wilcannia, on the edge of town, overlooking a bend in the Darling. Blacket’s hospital, completed in 1879,was built of locally quarried white quartzite sandstone, to a symmetrical cruciform plan. It featured central consulting rooms, and male and female wards on either side of the cruciform. Oriented north towards the township, away from the Darling, its major function was servicing the needs of riverboat traffic passing Wilcannia, “Queen City of the West” and the third largest Australian shipping port of the late 1800s.

Run along strict lines of exclusion and control, the hospital became, for the Barkinji, a “sick place” – where people needing treatment were incarcerated, “out of sight and out of mind”, out the back, away from community and country. In spite of this sorry history, Barkinji experiences have built the hospital and grounds into cultural memory, replete with stories and recollections of birth, sickness and death. Rather than erase these memories, the community was keen to preserve the site and buildings as remembered, to respect family associations and affinities developed over the years, and to reconnect this renewed site of healing with the river.

In 1998, Merrima won a tender to redevelop the hospital. Numerous additions had made the facility unsuitable for the current health needs of the community. Their brief was to provide an integrated multi-purpose

health centre, combining social services, community health, and respite accommodation. The design team’s input was extensive – they developed and presented seven design options, and attended twelve site visits, of which six were during construction. The project was facilitated by the Wilcannia Community Working Party – with representation from community elders, youth, government agencies and land council – which managed a regular consultation process to ensure community needs were met.

Shed(ding). The first move was to clear the hospital building of ad-hoc extensions, and retrieve the original Blacket structure. The internal fit-out carefully left intact several original features, which could not be restored and incorporated – such as coffered corrugated metal and timber ceilings in the female and male wards, masonry flues, and dormer window surrounds. These now remain concealed behind plasterboard ceilings, in case of more substantial future restoration. The restoration, including work done by the community under traineeship programs, focused on stone walls and re-pointing, reroofing and plumbing, painting and landscaping. This has returned the building and grounds to something of their original aspect. Where more complete restoration proved unviable, elements were stabilised and finished in a simple way. Overall, the impression is of a patchwork, registering the marks of incremental modification. Rather than crystallising an originary past, this restorative practice implies an ongoing future, with many opportunities for capacity building, trainee projects and community involvement.

The current operation focuses on primary healthcare, emergency, outpatients and respite care. There are initiatives for community-based education, outreach, home visitation and follow-up health maintenance – including a teleconferencing facility for families to communicate with others recuperating elsewhere.

Outside, the artist Badger Bates has made three paving slabs showing Ngatji, the river goanna and the Parntuu codfish. In Badger’s designs, all characters point away from the hospital, towards the community, to indicate that people are welcome – but also that returning home, to be with family and country, is the best way to health.

Working between. The project by Merrima reorganises hospital functions between the National Trust-listed Blacket building, a new linear wing facing the Barka, and a reception area between the two. The original hospital contains administration offices, ancillary spaces and consulting rooms. The new wing provides respite rooms to the east, a lounge and nurses station near reception, emergency outpatients adjacent to the ambulance bay, as well as staff facilities, kitchen, laundry and storage to the west. Circulation is by way of a central spine, with plenty of daylight, controlled solar access, cross ventilation, and a system of retaining winter solar energy through pitched metal linings oriented north.

For practical and cultural reasons, the mortuary facility is located at the far western end of the new wing, where access can be more discrete. Expressed as a separate mass, it is hinged northwards, and incorporates a stepped and screened external terrace which allows families to gather privately, and pay their respects.

The new wing is angled away from the Blacket building, so as to open up an entry space, and better address the Barka. It works in conjunction with the hospital, and a stone outbuilding on the southeast, to form a sheltered sunny courtyard. The plan’s articulation in two contiguous sections contributes much to the ensemble. The building hovers above a stabilised berm, turning with the river to reinforce landform and contour. The two sections are given individual orientations to the river, while the plan shape contains and protects the site to the north. This avoids a relentless and imposing wall on the river side; the buildings recede and don’t impose themselves on the landscape.

The reception distributes circulation south to the new structure, north to the old building, and east-west to sheltered courtyard and landscaped areas. As a place of orientation and passage – with many openings and ways through – it contests the formalism and hierarchical symmetry of the original building and site layout. Likewise, and with the greatest respect, the old building is reinhabited and returned informally to the river. It turns away from itself, into a more democratic site of access and egress, gathering and dispersing, engagement and disengagement. Literally turned inside out, it becomes reconciled to what it had forgotten, and in the process, is reconstructed and renewed.

Spatial moves in the design also have metaphorical value. Shifts in the building plan and form take up organic alignments. The angled cross-sectional profile appears to bellow or expand outwards. The architecture is made to be sensitive to the gestures and motions of place. Architect Dillon Kombumerri has spoken of an animate character to the buildings – that they appear to breathe, to be alive; that they evoke skin, gill, fin and lung; that they arc and spread like limbs and wings; that the are clad to read like armature and carapace; that they frame and register time changing by casting shadows onto their own surfaces and onto the ground.

How architecture works. Merrima’s original contribution is less a new building, than a new way of reading and capitalising on the potential of what is already there. The perimeter of Blacket’s building, together with several outbuildings and sheds, provides a framework for simple interventions. The new buildings use these to help zone the site, and create a layered and sequenced organisation. External spaces are as important as internal rooms. In some cases, internal spaces read as external – in the western corridor, for example, where a combination of the cross-sectional profile, splayed upper walls of the southern sequence of rooms, and natural light, create the impression of a shaded street lined with discrete small-scaled buildings. In this way, the inside is turned inside out, and returned to country – that is, to an outside that had always been there.

This is Merrima’s proposition: that architecture might consist primarily in how the in-between is conceived, shaped, furnished, and opened up to inhabitation. New spaces are made between buildings, between river and town, between turn of the century and contemporary health practices. Site planning, and the relationships between old and new buildings, provide opportunities for places that could be later spliced and tucked into recesses as needs change. Now that the buildings and site belong to the river, they harbour a way of being close to place and country – protecting and making room for memory and for stories. In this way, architecture “works”. It contributes to cultural sustainment by reconciling person and place, community and country. Its function is not disembodied or abstracted from the socio-cultural, but grounded in it. Rather than being isolated, objectified, aestheticised or monumentalised, architecture exists primarily as a site of cultural practice – and its success is judged inasmuch as it affords and promotes this practice.

Credits

- Project

- Wilcannia Health Service

- Project architect

- Dillon Kombumerri

- Architect

-

Merrima, DPWS

- Project Team

- Kevin O’Brien, John Moschatos, Phil Senior

- Consultants

-

Builder

Lahey Constructions

Electrical consultant DPWS—Ian Gordon

Hydraulic consultant DPWS—Ian Chappe

Interior designer Merrima, DPWS—Alison Page

Landscape architect DPWS—Nicole Thompson

Mechanical consultant DPWS—Jack Wocial

Project manager DPWS

Quantity surveyor Page Kirkland—John Milliken

Structural and civil engineer DPWS—Vijay Badnwar

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

- Client

-

Client name

Far West Area Health Service