Working in Asia brought together five women in architecture – all with experience in Asia and some with family backgrounds there. The focus on women’s architecture and ambitions and not on what had prevented, curtailed or restricted their careers was refreshing.

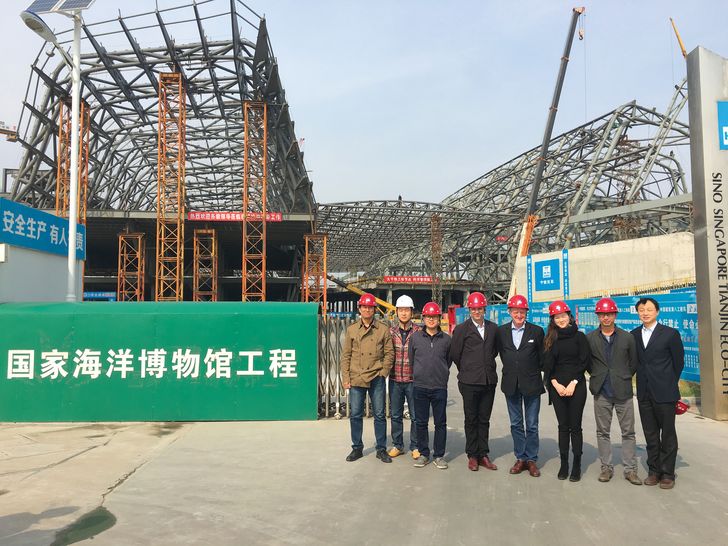

Architects from Cox Architecture and Tianjin Architecture Design Institute resolving design coordination issues between the services and the complex form (2016).

Image: Anya Meng

Of the five speakers, three – Anya Meng and Christina Na-Heon Cho (both of Cox, Brisbane) and Natasha Chee (now a project manager at CBRE, Brisbane) – identified as 1.5-generation migrants: those who moved to Australia as children or whose families moved here shortly before they were born. They learned Asian spoken language skills from their parents but were schooled and studied architecture here. Their approach seemed to demonstrate that the world is where they belong, not one city or country, and this attitude has propelled them into career and life-changing moves. The other speakers – Kali Marnane (a University of Queensland architecture PhD candidate) and Kirsti Simpson (a principal at Hassell’s Brisbane studio) – also share a vision of an increasingly internationalized Australian architecture scene and have sought opportunities to engage with Asia. This reflects an important change in Australian architectural practice. We are educating our graduates for a global architectural industry and these women reflect how movement between Australia and Asia has become fluid and part of everyday practice .

There were broader lessons to be taken from the diverse experiences presented. The first is that openness is valuable, whatever the forces of introversion and fear might tell you. Closing down connections or shunning cultures that don’t share our current traits is not only cruel, it’s an opportunity lost. Novel cultural experiences can and did lead to new businesses, networks and modes of practice. Marnane, for example, worked in Ahmedabad’s slums in India in the blistering heat, communicating in her broken Gujarati, all while successfully formulating a project to research the morphology of public space and to better house the poorest communities.

The second lesson is more local: Australia’s multiculturalism is still one of our great advantages in the world. Those of us with just one language or one cultural background can learn how to be adaptable from those who are practised at it and we don’t even have to leave Australia to experience that. Meng spoke of working in Brisbane and translating a colleague’s emails arriving in Mandarin from China, at first using a combination of Google Translate and her mum’s assistance, and later learning to write Mandarin to enable fully bilingual communication.

Anya Meng on Cox Architecture’s second official site visit to the National Maritime Museum of China, Tianjin ( 2016 ).

Image: Li Ye

The third lesson is obvious but critical: Asia is a diverse place. The difference between an Ahmedabad slum and Beijing is obvious, but so too are there marked differences between Korea, China and other Asian nations. To imagine “Asia” as a homogeneous mass is a mistake. Nevertheless, some commonalities across the region were characterized in each presentation: Asia is growing fast and buildings are going up faster. Work on both residential and civic projects is unprecedented in terms of scale and speed of construction and it offers huge opportunities for architects to gain experience in building and design.

The final lesson seemed to me to be that women, and especially younger women, really do approach things differently. The speakers were strikingly open and ready to share both struggles and successes. Their honest, reflective, funny, charming stories were in stark contrast to the bravado and the facade of invulnerable confidence that so many speakers project. Perhaps the designated women’s “space to speak” provided the safety from which such vulnerability and genuine insight can flourish. The presenters were all accomplished, and rightly proud of their achievements, but they did not shy away from sharing their shocks and difficulties working in Asia – the local politics and hierarchies, the smog, the distance from family and friends, the cultural differences.

This event offered insight into how to take a fork in the road, how to move into a future that is simultaneously engaged with Asian growth opportunities and with what architects want: challenge, fresh chances and exciting projects. These five women’s stellar careers provide invaluable insights and inspiration. However, the crowd was largely their young women colleagues and women academics, like me, who once taught them. It’s time that space to speak for women in architecture also becomes a space for men and those of other generations to listen and share too. Only when these open conversations become two-way will the full benefit of new futures be shared across the profession – for any architect, working in any part of the world.

— Kelly Greenop is a senior lecturer at the School of Architecture at the University of Queensland. Kelly is affiliated with both ATCH – the Architecture Theory Criticism History research centre – and the Aboriginal Environments Research Centre within the school.

Working in Asia was held on 29 March 2017, part of the Asia Pacific Architecture Forum in Brisbane, 18–31 March. It was hosted by Gadens Lawyers and was supported by the University of Queensland and Parlour: women, equity, architecture.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 7 Mar 2018

Words:

Kelly Greenop

Images:

Anya Meng,

Kali Marnane,

Li Ye

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2017