In November 2012, Alison Nobbs and Sean Radford were invited by the Swiss Fondation Jan Michalski pour l’Ecriture et la Littérature to submit a design for a small writer’s cabin. The foundation was established in 2004 to support the creation of literary works internationally, and annually awards the Jan Michalski Prize for Literature.

Nobbs Radford Architects was the only Australian practice invited to submit its ideas for a cabin, along with fifteen other architecture practices worldwide, including Boyd Cody Architects (Ireland), Rintala Eggertsson Architects (Norway), Andreas Fuhrimann Gabrielle Hächler Architekten (Germany), FRPO Rodriguez & Oriol Architecture Landscape (Spain), Studio MK27 (Brazil), Dyan Belliapa (India), Blank Studio Architecture (USA), Coast (Denmark), SHED Architecture & Design (USA), SC Studio Architects (South Africa), Jean Gilles Décosterd (Switzerland), and Atelier Bonnet (Switzerland).

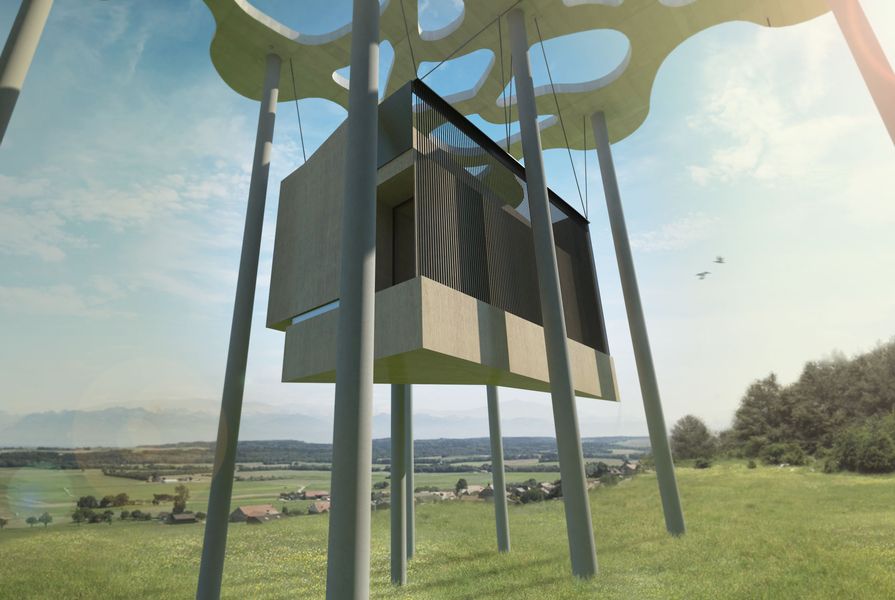

The writer’s cabins are to be housed at the new Foundation headquarters, its House of Writing, at Montricher, in the Swiss canton of Vaud. Designed by Architects V. Mangeat and P. Wahlen, the House of Writing includes a library, exhibition space, auditorium, and offices set within a forest of slender concrete columns supporting a canopy of honeycombed concrete. Cabins selected by the Foundation will eventually be constructed amid the faux forest, for visiting writers to stay in as part of a writers-in-residence program.

Peter Salhani: Why was Nobbs Radford Architects invited to submit?

Alison Nobbs: It was quite an honour to be asked alongside such esteemed international practices, but we don’t know why for sure. Our theory – and it’s pure speculation – is because of the the Lilyfield House we did a few years ago. That project was widely publicized in Europe and the scale of it relates really well to the writer’s cabin.

PS: What were the key elements of the brief you were responding to?

AN: It had a really interesting set of parameters. The structural fixing system was set, the envelope was fixed, the floorplate was fixed (around forty to fifty square metres, based on structural capacity and anchoring points) and it could be either one or two stories in height. Most interesting of all was that it had to fit within a forest of concrete columns already built, under the honeycombed concrete canopy.

PS: What was your conceptual approach to the brief?

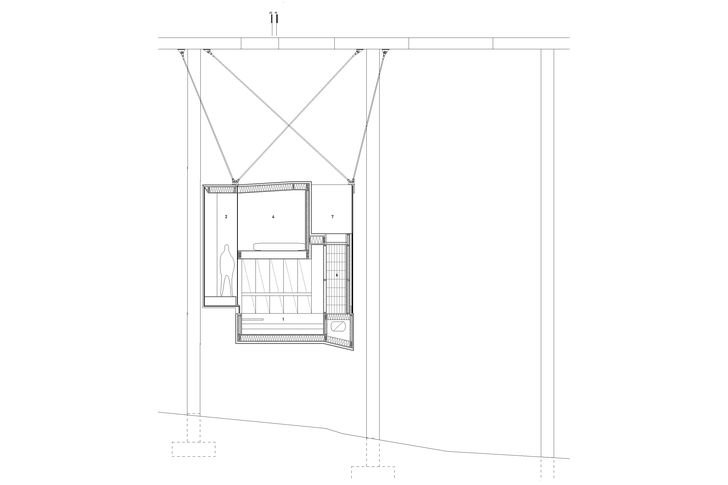

AN: Our idea revolves around the idea of suspension – a cabin strung up in the canopy, as opposed to a load-bearing structure. The primary structural logic is that the elements are held in tension: because the cabin is suspended from the canopy on cables, its two components overlap but don’t actually touch. The two elements are the roof and wall plane and corresponding floor and wall plane. This tectonic relationship can only be achieved because they are hanging elements, and there’s no load-bearing relationship between them.

Section B: Suspended writer’s cabin design by Nobbs Radford Architects.

PS: What were some of the interesting aspects of designing the cabin?

AN: Because it’s just meant to be hanging there, it can be viewed from all angles, including from underneath. This opens up possibilities of views from inside that you don’t normally get, so we’ve opened up sections to the canopy above and the ground below. Also, because of the size expectation, it was a challenging exercise in how to evoke different moods in such a confined area. The utility spaces of kitchen and living area open to the largest of the cabin’s dozen or so main apertures. The writing space is more compressed with a low ceiling and sunken floor that can be seen from underneath. This is a more introspective space with smaller and fewer openings for more controlled and more carefully framed views.

PS: How did you envisage what you thought the space for a writer should be?

AN: We talked to a few writers and publishers to get an idea of how they work, but to be honest, the repsonses were so varied as to be inconclusive. I guess ultimately we made an assumption that the act of writing needed a more contained, introspective and secure space – to allow the writer to not feel tenuous, as we felt the act of writing itself was tenuous enough. The other idea we held in our minds was that most writers would have a love of books, and we felt books should be part of the space.

PS: How did you manage this?

AN: A series of shelving units wraps from the floor up along the walls along the circulation route from living through to sleeping and writing areas – so the occupant literally moves you up and over and through an ever-changing bookcase. Like walking through a kind of library. The bookshelves are also legible externally – slim vertical timber slats are squenced in a denisty and rhythm that alludes to the pages of a book.

PS: Has working on this design altered or expanded your approach to other projects?

AN: It has, in quite different ways. There was something about this being a very condensed piece of architecture that required a discipline to achieve that diversity of function and narrative in such a small space. But there was also a freedom in thinking about the building as an object hanging in space; it’s literally abstracted from the ground plane, the neighbouring buildings, the street, so we were working with a very different context. There’s a dividing screen running through the interior made up of the cables that not only expresses the structure, but it also makes the structure more integral to the experience of the space, beyond merely leaving a structural form exposed. It’s very satisfying to work with those kinds of ideas.

PS: What happens next with the cabin?

AN: Stage one, the design phase is over, and all the submissions are with the Foundation. Their plan is to hold an exhibition of all the designs later in the year, and to start building the selected cabins sometime in 2015, so it’s a long wait for stage two.