Rory Hyde: How did you first get involved in designing for space?

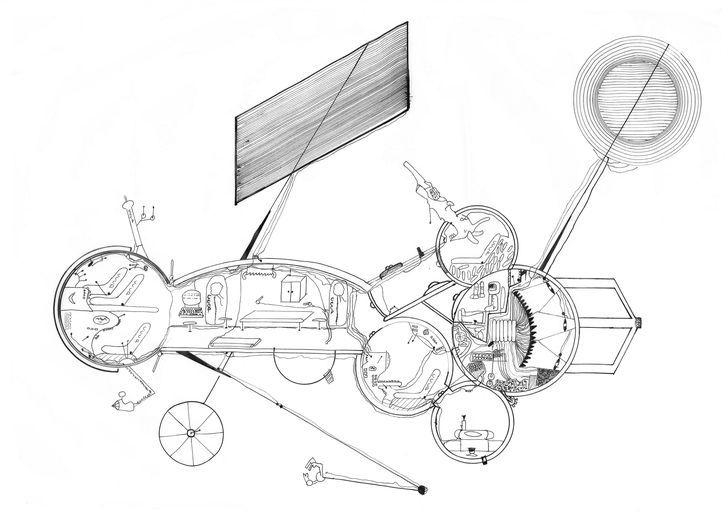

Xavier De Kestelier: Going right back, my dad took me to an exhibition on space, in Brussels, when I was about 12 years old. It was the end of the Cold War and there was a bit of one-upmanship going on between the Americans and the Russians. The Americans brought a big blow-up space shuttle, but the Russians brought the training module for the Mir space station – the real thing. And you could go inside it. I saw where the buttons were, where the wires were, where the astronauts were eating, where they were working. And when I got home, the first thing I did was start drawing spaceships. My mum found the drawing the other day!

After going to a space exhibition at the age of about 12, De Kestelier began drawing spaceships.

Image: Xavier De Kestelier

So, that’s the deep history. Then, once I was working in architecture, I was speaking at a conference in Toronto – in 2006, I think – and I saw a 3D printer for the first time, in the basement at Waterloo University. I was working at Foster and Partners, and I went back and said to the CEO, “We need to get one of these.” I was able to convince him in about two minutes. Eventually, we went on to set up a whole department.

Around this time, we were working with Enrico Dini, an engineer who was one of the first to do large-scale 3D printing. He mentioned that the European Space Agency [ESA] had approached him to do some research into it, but that he needed to team up with a bigger company. So, I said we [Fosters] would do it.

The ESA was interested in having us explore very technical questions: “Can you print in a vacuum?”, “Can you use moon dust?” The ESA wasn’t quite sure why there were architects on the team, but we imagined a project – a 3D-printed moon habitat – and the renders went a bit viral. And they were really happy because it evoked a future that was based on the research. It wasn’t science fiction, it was science fact.

RH: How does 3D-printing on the moon work? What do you need to know about designing architecture there?

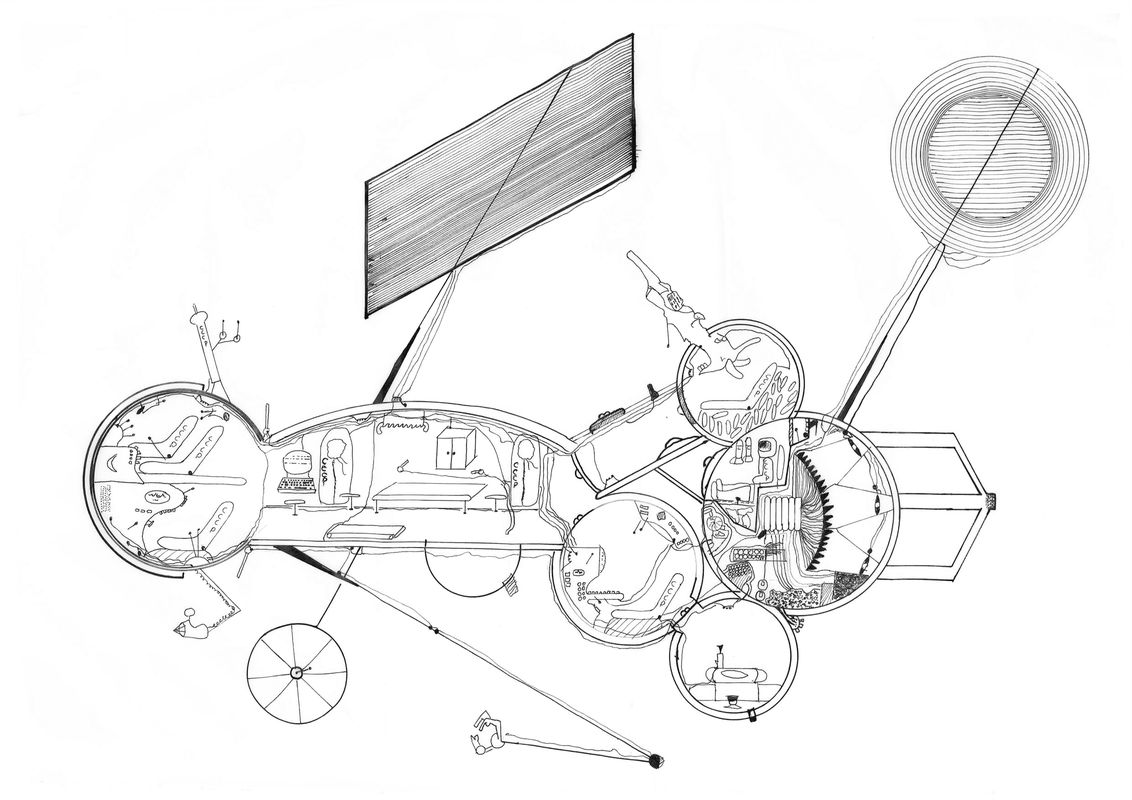

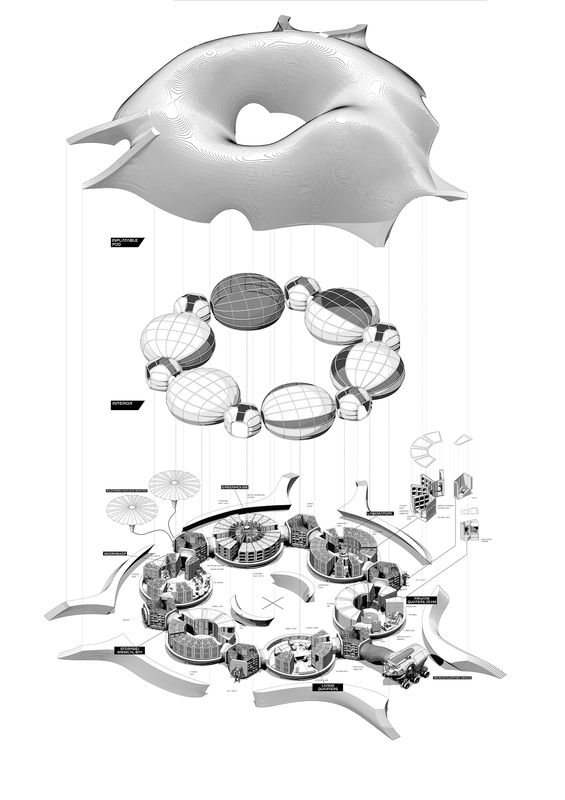

XDK: The way I like to design is to go back to first principles. To ask yourself the question: “Why is something a certain way?” So, for the moon, you start with the environment. You have one-sixth of the gravity, which is an architect’s dream, because you can make things thinner than on Earth. There’s no air; you’re in a vacuum. There’s no atmosphere to protect you from radiation or from micro-meteorites, which is a bit of a problem. So, the ideal would be to live in a cave. There are maybe some caves on the moon, called lava tubes, but we don’t know where they are or how big they are, so what we’re really doing is creating these caves. We 3D-print a shell structure, and then underneath, we’ve designed an unfoldable, inflatable structure that holds the pressure – and this is where the astronauts live.

Previously a partner in Foster and Partners’ specialist modelling group, De Kestelier tries to bring the power of design into space architecture.

Image: Hassell

RH: How many people are we talking about? Is it about small bases, or cities?

XDK: I don’t think the goal for living on other planets is – as Elon Musk says – to get a million people to Mars. The better analogy is the Antarctic, where we have research bases with small numbers of people conducting science and research. Nobody is going to really “live” on other planets because nothing is as good as Earth, at the end of the day.

So, the research I’m doing at the moment is looking at how to design a moon habitat for up to 144 people – that’s Dunbar’s number. Beyond that, the social structure starts to collapse. That’s the number we got from the anthropologists we are collaborating with on the proje ct.

RH: What does your team look like? What are the other kinds of experts you are working with? How many of you are technical, and how many are social or design?

XDK: It’s probably about fifty-fifty. There are space psychologists, people who know about Antarctic bases and have overwintered, medical experts, geologists and mining experts, space systems engineers. We’re working with a Mars meteorologist – they know all about the weather on Mars. There are radiation experts, robotics engineers, and even Sanjeev Gupta, one of the leaders of the Curiosity rover mission [NASA’s attempt to determine whether Mars is, or was, suitable for life]. It’s a huge variety of people and it’s not always just the hardcore space people.

RH: What skills from architecture have you found useful in working in this field?

XDK: A lot of the people in this field have degrees in space engineering and a lot of technical stuff. I’m a bit technical, but I’m not super technical on space. I feel that’s a good thing because what I try to bring in space architecture is the power of design itself. We have to believe a bit more in our own profession and in the value of it.

I often go back to the example of the industrial designer Raymond Loewy, who NASA brought on to review the design of the Skylab space station in 1973. The astronauts were going to be orbiting around the Earth for six months, but the engineers hadn’t even put a window in, as it would have been a weakness in the shell of the spaceship. Loewy put a window in, and he also designed a table for the astronauts to face each other while they were eating – a fundamental part of human communication.

In these technical fields, the specialists always think that, as an architect, you’ll come in and choose the colour, or design a doorknob. But it’s not about that. These space agencies or engineering firms are always surprised by what we bring. They think that design is just about making it pretty. But we’re not just a little add-on; we’re central in the process. We’re about how you organize space, how you plan it, how you put it all together. I think that, as architects, we’re actually really good at that.

RH: When you say “organize,” do you mean the building itself, or is it about organizing the process? About negotiating between different forms of knowledge?

XDK: I think you’re right – we’re kind of playing that role of conductor, too. For example, on one of our NASA projects, we got all these experts and we brought them all together for an architecture- style crit. This was a bit of a shock to the scientists, who are used to publishing their work in peer-reviewed journals. Instead, I gave them all a red pen and said, “I want you to really harshly critique what we’re doing here. Question everything.” So this was a completely different world. We had some arguments, but it was fun. Everyone was really engaged. Now, we’re putting this process into our research proposals. The crit is an interesting process, especially when you open it up to other kinds of expertise.

RH: Do you think that any of these projects will ever be built? Does it feel like you’re working on science or fiction?

XDK: Oh, totally – we will build one of these. Very soon.

— Xavier De Kestelier is head of design at Hassell, where he leads design technology and innovation across all disciplines and regions. He is also a director of Smartgeometry, a non-profit educational organization for computational design and digital fabrication.

Source

People

Published online: 27 Jan 2022

Words:

Rory Hyde

Images:

Hassell,

Hassell and EOC,

Xavier De Kestelier

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2022