Architects rally to support bushfire-ravaged communities

The devastating bushfires of the 2019-20 “Black Summer” spawned an unparalleled community response. An estimated $500 million was donated by the public, local communities rallied around those who had lost their homes and, in cities, thousands marched in protest of government inaction in addressing climate change. Architects too rushed to offer support to affected communities, launching the Architects Assist program in January to offer pro bono design services. Founded by Tasmania-based architect Jiri Lev and facilitated by the Australian Institute of Architects, the program aimed to put architects and other built-environment professionals in touch with individuals and communities to design architecturally considered, resilient and sustainable buildings. By July, more than 600 firms had signed up, along with 1,500 architecture students and graduates keen to assist recovery efforts. Lev, who together with his wife Aleksandra toured bushfire-affected communities to offer advice and referrals, estimates that between 100 and 200 projects have been initiated through the program, though some of these have since stalled. Among those progressing are a modest artist’s cottage in Victoria’s Gippsland by Pete Collings Architect, a food hub in the Adelaide Hills by Butcher Brown Architects, and six ongoing bushfire recovery projects by Dickson Rothschild spread across southern New South Wales. Architects have also raised more than $12,000 through the Institute’s “Architects Donate” initiative, which will be used to support rebuild projects.

The shock of the pandemic

The global COVID-19 pandemic, the ensuing lockdowns and the deepest economic crisis in 90 years sent shockwaves through Australia’s construction and architecture sectors in 2020, with firms reporting widespread cessation of projects, mass job cuts and overall business uncertainty. A series of surveys taken by leading industry bodies throughout the year offers an (admittedly incomplete) picture of how the industry has fared. A preliminary “pulse check” survey conducted by the Association of Consulting Architects Australia (ACA) in mid-March found that 57 percent of the 1,341 respondent practices had already had projects cancelled or were expecting projects to cease. In June, a survey conducted by the Australian Institute of Architects found that 64.87 percent of respondents had projects stalled, while 27.27 percent of practices had been forced to lay off or stand down staff. Unemployment among the profession had risen 2.35 percent and the rate of full-time employment had plummeted 10 percent. And in late August, an ACA survey of practices in the hardest-hit state of Victoria found that around 80 percent of practices had had projects cancelled or put on hold, with $2.3 billion worth of projects cancelled and $4.55 billion on hold. That same survey found that around one in five practices had made changes to employment arrangements, most commonly by reducing working hours (50 percent), changing roles (33 percent), reducing pay (32 percent), standing down staff (15 percent) or instituting redundancies (12 percent).

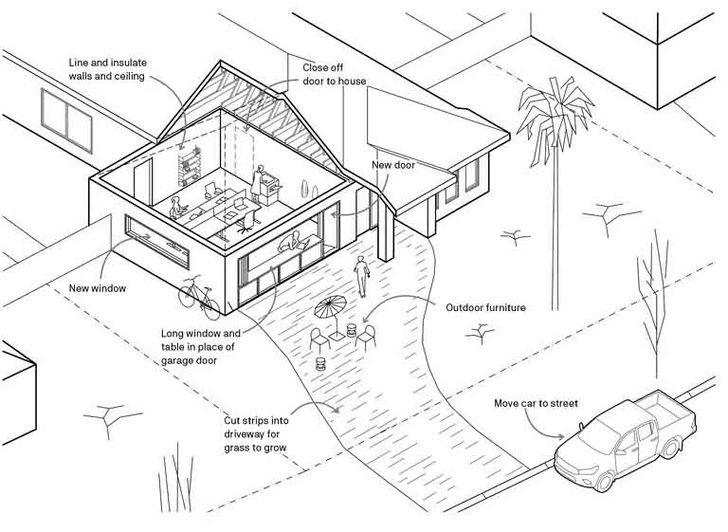

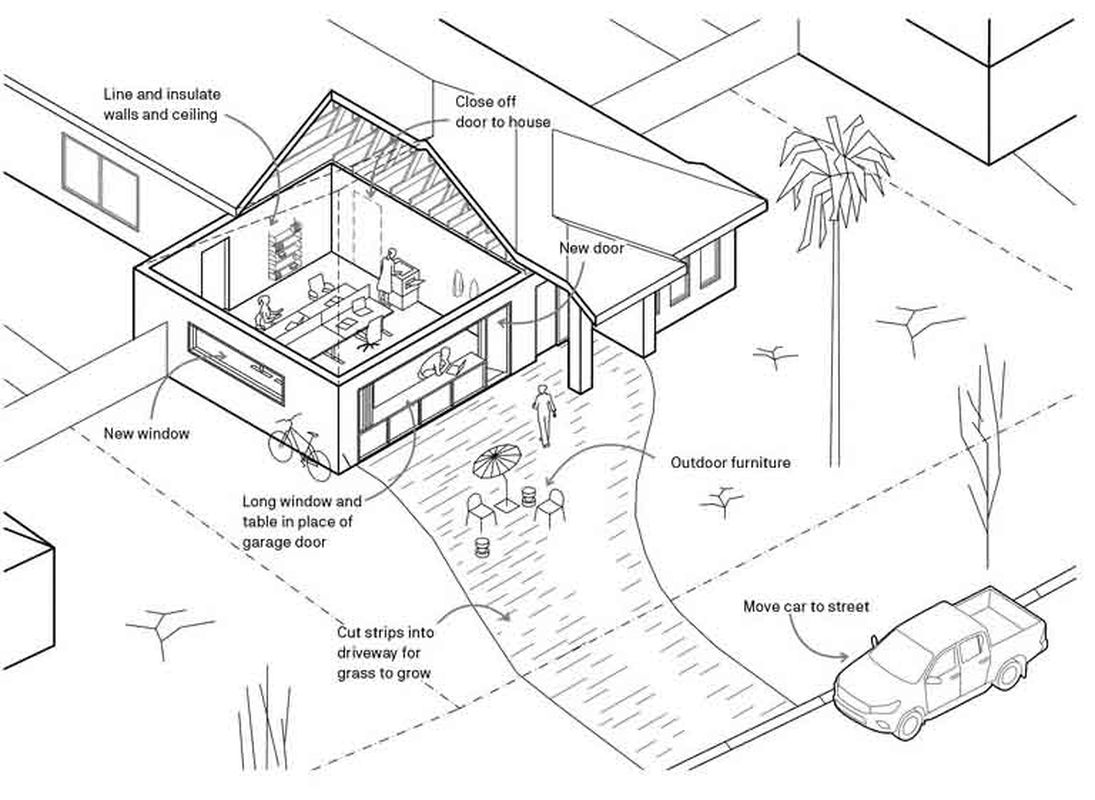

Rory Hyde imagines a “neighbourhood office hub.” Could this be the post-COVID future of work?

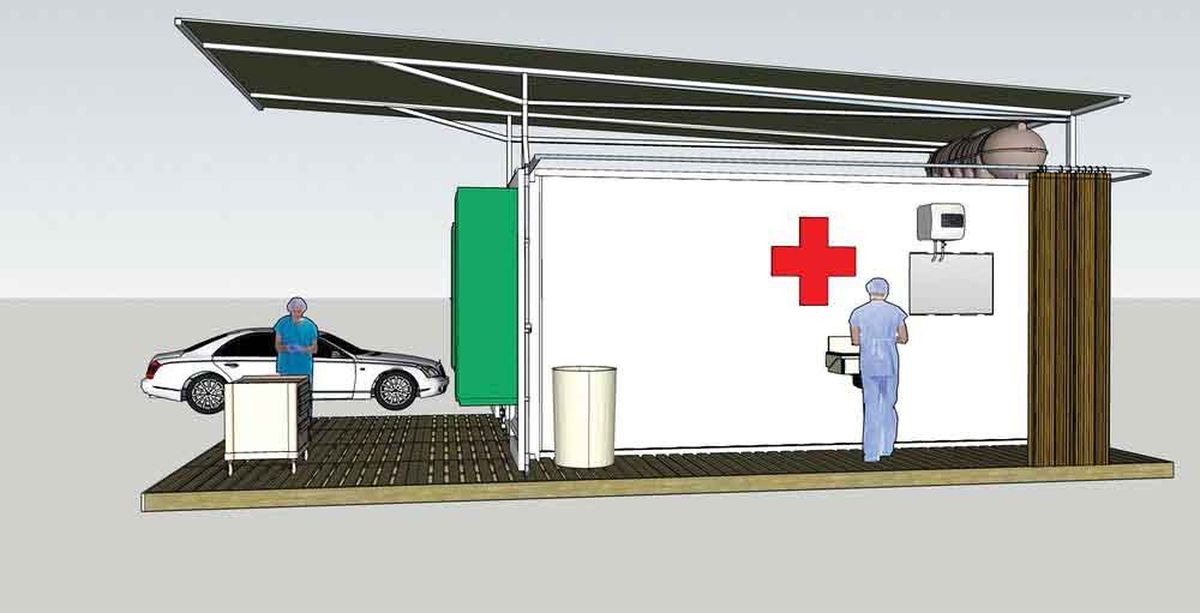

How can architecture respond to crisis?

Throughout human history, crises have upended social relations, reshaped cities and triggered novel architectural responses. In the September/October issue of Architecture Australia, Philip Goad looked back to past responses to crisis, from the spatial reconfiguration brought on by the Black Death to the Keynesian capital works projects of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. He writes, “The architecture of crisis is an intrinsic and everyday part of urban existence that continues to shape our cities, whether we like it or not. Remarkably, ventilation continues to remain key, as does the right to private outdoor space. While the concept and prospect of vaccines make many historic examples seem quaint, old-fashioned and temporary, the architectural lessons of crisis remain with us. There will always be a need for certain spaces to be repurposed during crisis. There will always be a need for ephemeral structures to cope with the spatial challenges of immediate crisis. There will always be a need for emergency domestic shelter. There will always be a need to reshape and reform our cities in preparation for the next crisis.” In the July/August issue of Architecture Australia, Rory Hyde asked what sort of world we want to re-enter post-COVID, and how architects can grasp the opportunity: “Architects have the ability to synthesize the complex demands of this new world, to transform them into an equitable and exciting future, and to design the practical means to bring this future about. In this brief moment of upheaval, we have the chance to repurpose our cities to prepare them for the shocks of the coming century. Having demonstrated our civic purpose and strategic ability, reaffirming our value in the eyes of the public, we might even save architecture, too.”

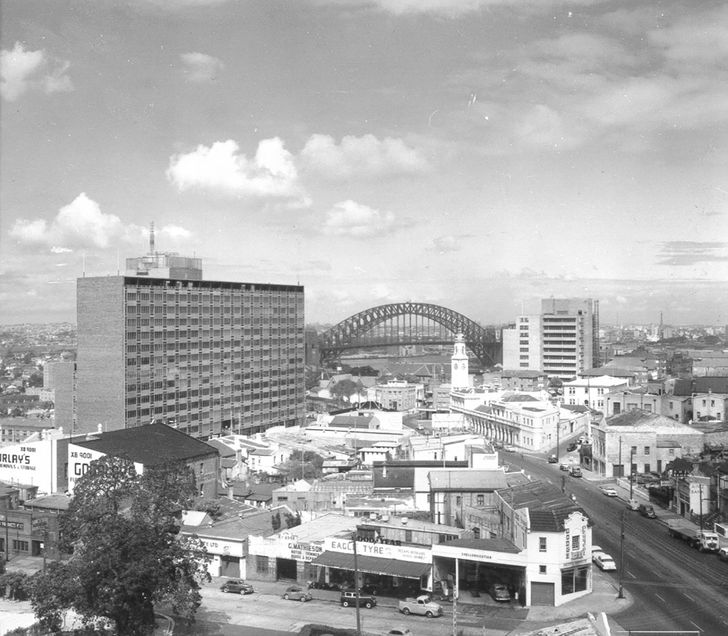

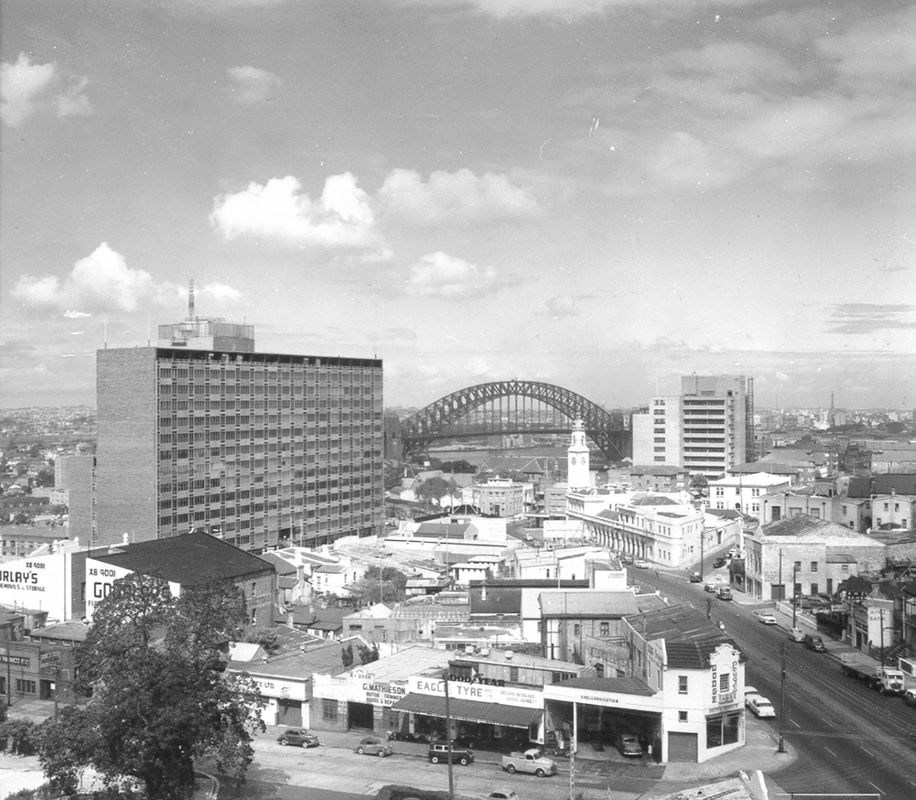

The existing North Sydney MLC building by Bates Smart and McCutcheon, completed in 1956.

North Sydney modernist icon under threat

One of the more controversial development proposals of the past year has been the plan to demolish and replace the 1956 MLC Building at 105–153 Miller Street, North Sydney. Designed by Bates, Smart and McCutcheon, the modernist office building was the largest building of its type in Australia at the time of its construction. Its local heritage listing describes it as “a seminal work in the development of high-rise buildings in Australia.” Bates Smart is also the architect of the proposed replacement – a sculpted, tapered commercial tower with a naturally ventilated atrium. In documents submitted to the North Sydney council, Bates Smart stated that it had worked with the building’s owners for more than a decade to find a way to refurbish it, but the plan was eventually deemed unviable because of an “unsympathetic relationship to the heritage of MLC [and] overshadowing of [the adjacent] Brett Whiteley Place.” Residents, architects and modernism enthusiasts have blasted the demolition proposal, however, arguing that the MLC building is “one of the most important mid-century modernist buildings in Australia.” North Sydney Council has been flooded with submissions related to the proposal, while, at the time of writing, more than 1,700 people had signed a petition, launched by modern architecture preservation organization Docomomo, protesting the development. “The evidence presented in the development application for the replacement of the MLC Building does not demonstrate in any detail that alternative strategies to demolition have been pursued with any rigor,” wrote Docomomo president Scott Robertson. The Heritage Council of NSW is considering whether the building is of state significance.

Atlassian’s Sydney headquarters tower by Shop Architects and BVN.

World’s tallest hybrid timber tower for Australian tech company

Australian tech giant Atlassian caused a stir in June when it unveiled the design for its Sydney headquarters by New York-based Shop Architects and Australian practice BVN. To be built using mass timber construction, the tower is set to become the tallest hybrid timber structure in the world, standing at 40 storeys. It will be located adjacent to Sydney’s Central Station and will be part of the New South Wales government’s planned technology precinct for the area.

Shop Architects and BVN were selected as the architects following a global search. “The building is designed in four-storey ‘habitats,’ each habitat has a park that is fully naturally ventilated, the innovative ventilation strategy for the building also permeates the floorplates,” said BVN co-CEO Ninotschka Titchkosky. The building will target a 50 percent reduction in embodied carbon and energy compared to conventional construction and Atlassian has committed to operating on 100 percent renewable energy with zero emissions. The building will be constructed with a combination of mass timber, concrete and steel. “For a lower height building you can build totally in timber; at 40 storeys, we need to hybridize the structural system,” Titchkosky said. “This project is not just about being green, it’s a whole-systems approach to design, construction and habitation. It will demonstrate that change is possible and has many advantages for the planet, our cities and business.” Next to the Atlassian headquarters, at 14–30 Lee Street, Fender Katsalidis and SOM will design another tech-focused office precinct for Transport for NSW. The design of the precinct references the surrounding heritage of the precinct.

Richard Leplastrier.

Image: Mark Rogers

‘National living treasure’ Richard Leplastrier on film

Amid the chaos and consternation of 2020, a new documentary on Richard Leplastrier, the Australian Institute of Architects’ 1999 Gold Medallist, offered a moment of reprieve. Airing on the ABC in May, the film took writer, directer and producer Anna Cater 15 years to make. It takes a detailed look at the life and work of the much-lauded architect. “I grew up in a house in Canberra that was designed by an architect called Russell Jack of Allen Jack and Cottier. It gave me a love of architecture,” Cater said. “Peter Stutchbury designed my apartment 30 or 40 years ago and through him I met Richard. What attracted me to make a film about Richard was not only that he’s a great architect but he’s also a really interesting person.”

Cater began making a film about the design and construction of Leplastrier’s Blackheath House. “This was before Grand Designs,” she explains. “I filmed that house from the beginning to the end and then I realized a documentary about Richard needed to be expanded.” The filmmaker formed a close bond with the architect, and the footage takes the audience into the architect’s home to catch a glimpse of the way he lives. It also takes the viewer to Kyoto, where Leplastrier was mentored by Japanese professor Masuda Tomoya, and explores his other mentors, Jørn Utzon and Australian artist Lloyd Rees. Cater hopes the documentary will introduce new audiences to Leplastrier and his extraordinary talent. “Richard is like one of our national living treasures – not just as an architect but as a person. He’s intelligent, charming, he likes to be a bit of a ratbag. I really think it’s important to have films about these people because they’ve got so much to offer.”

Leplastrier’s Palm Garden House was also recognized with the Enduring Architecture Award at the 2020 National Architecture Awards.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 18 Dec 2020

Words:

ArchitectureAU Editorial

Images:

Aleksandra Lev,

Mark Rogers

Issue

Architecture Australia, November 2020