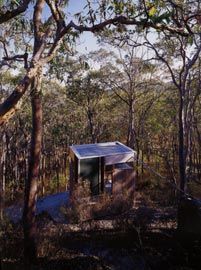

The “wheel-less caravan” seen from above.

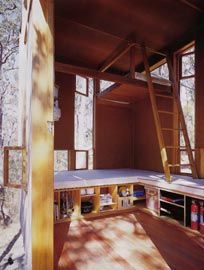

Interior view, with ground level sleeping areas and the ladder to the upper level sleeping area. Horizontal and vertical windows frame the landscape and sky.

Overview of the unpacked interior.

Details. The building, clad in everyday materials with some finer detailing, is a “box with some nice bits”.

Details. The building, clad in everyday materials with some finer detailing, is a “box with some nice bits”.

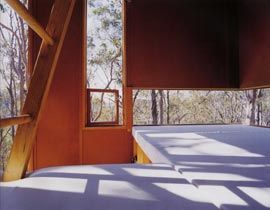

Looking over the layered deck into the landscape.

The box seen from the south-east, showing the disposition of the zigzag windows.

SITUATED ON THE architectural scale somewhere between Peter Stutchbury’s Israel House and the tent, architect and builder Drew Heath’s Zigzag House abandons the desire for permanence in architecture and examines minimum living requirements and our relationship with place. Heath speaks of human consumption with open disdain, “We are disgusting as human beings the way we live – we really have lost control… there’d be more space in the world for us to go walking if we reduced our consumption of everything.” This project is an attempt to make an architecture predicated on a questioning of client requests, and realized through formal invention and structural ingenuity rather than large-scale solutions.

Design. The Sydney-based clients had purchased land near Wollombi, two-anda- half hours north of Sydney, with the intention of constructing a traditional residence embodying an enclosed and embedded place of refuge. Heath, claiming he was “the wrong architect” for that particular brief, proposed a smaller dwelling that offered a camp-like existence from which the environment could be observed and discovered.

This scaling down also had the added benefit of an expedited approvals process. The architect dismisses any seriousness in the building describing it as a “wheel-less caravan” that deliberately references the surface and colour of this particular Australian landscape. Conceived through a single beer coaster sketch, the original drawing illustrated a box with its super-graphic of zigzag window openings resting alongside a deck that vanished to infinity in the landscape. This diagram defined the proposed physical program of contemplation within the nine square metre box and observation from the fifteen square metre deck. Initial discussions re-sited the building from the top of the hill to further down the slope where Heath felt more comfortable allowing the human experience to be subjugated by a natural one. The box has three sleeping areas: two at ground level and a bunk on a suspended mezzanine. A water tank is located uphill supplying a sink below the deck. A stone tower at the end of the deck near the box was proposed for a fireplace but was rejected due to budgetary constraints.

Construction. Following a three-week approval process based upon 1:100 drawings, which revealed little more than a graphic representation, an empirical process of construction began. Heath constructed the building in between travels from Sydney to Gloucester, further north, where he was completing another project. Ideas were tested and built on site. For example, a cattle ramp to the front of the deck was removed once the suggested front access path was moved to the rear of the box.

The structure is a twisted off-centre hard wood frame, which allows window or door openings at every corner, bound together with a plywood beam at parapet height that provides stability to the framework. This structure is clad in large “poor” materials (masonite and cypress pine), providing quick and inexpensive cover, with selected areas receiving a finer scale of detailing. It is not so much a piece of joinery, as a box with some nice bits. This principle is carried through to the deck where a sitting edge is defined by a scale change of timber. Heath maintains that any material can be built with regardless of its origin and he rejects the notion of the “precious material”. The cabin seeks to camouflage itself through the chameleon-like, or more appropriately goannalike, colour applied through a layered painting process.

Experience. Arriving at the Zigzag Cabin has the same quality as arriving at an outpost or base camp. The box with all its stored living apparatus is unpacked.

Hammocks are hung, kitchen assembled on the long step/dining bench and a fire started in a carved recess in the hill behind (fire bans permitting). Heath openly admits his preference for this dry, harsh landscape, where you can “scramble on the rocks” – a landscape not traditionally associated with his Tasmanian origins. In this environment survival is difficult, and the project occupies a precarious position in the landscape. On the day I visited, temperatures were in low forties. With helicopters water-bombing nearby, and with only one route out, this tenuous position was constantly reinforced. The price paid for this exposure is a heightened relationship with place. Windows at sleeping level frame views of eucalypt trunks and distant ridgelines. Vertical windows allow an appreciation of the connection between earth and sky. Upper level windows afford views of both tree and sky canopies. Constant “trimming” of these windows allows the building to perform thermally without the need for exterior sunshade protection. Some things remain unfinished such as a handrail and a roof deck to provide another space for contemplation. This is architecture that demands human involvement and interaction to make the experience enjoyable and memorable. It provides some, but not all, of the necessities for living and this deprivation, like camping, is its most valuable quality: providing an escape from an urban condition of convenience.

The Zigzag house received the 2003 Dulux Colour award in the Residential Exterior category.

Images by Brett Boardman