The architect’s own home has long been a source of fascination as well as fodder for richly illustrated coffee-table publications. Recent examples include Bethany Patch’s 2017 Architects’ Homes, Stephen Crafti’s 2015 Architects’ Houses, Gennaro Postiglione’s 2013 The Architect’s Home, Anatxu Zabalbeascoa’s 1995 The House of the Architect, Michael Webb’s 1994 Architects House Themselves and Miranda H. Newton’s 1992 Architects’ London Houses. All these publications fit into a well-established genre in architectural writing that emerged in the late nineteenth century when, in conjunction with the professionalization of the architectural profession, periodicals such as The Architects’ Journal and Country Life published recurring features on architects’ own homes. These features were generally rather formulaic in terms of both layout and content. Emphasis was commonly placed on the aesthetic qualities of the house and the key recurring theme was the veneration of architects and their realizations. The aim was clear: to showcase the superiority of architect-designed dwellings and (thus) promote the services of the architect.

The final two pages of Crafti’s Architects’ Houses book, for instance, subtly list the contact details of all the architects whose houses are featured in the book. A less subtle tack to promote the services of the architect was adopted in a 1974 book, Houses Architects Design for Themselves. In its introduction, the editor unapologetically states:

“There is something very special about a house that is special for you – which is why … some people (bless them) go and find a good architect and enter on the time-consuming, mind-bending, sometimes frustrating, but always rewarding process of having their house designed and built just for them. Living in an everyday kind of house – compared with living in a house that really fits your way of living – must be like being married to a woman who has never bothered to learn to cook well; you can get used to it, but you miss something every day of your life.”

Nevertheless, even in these largely promotional publications on architects’ own homes, critical asides were sometimes made. As early as 1936, an article published in Country Life, entitled “An Architect’s Own House,” for instance, opened with:

“We know what the doctor prescribes for us, but does he take his own medicine? In the same way we might ask, does the architect live in the kind of house he recommends to others? In secrecy let it be said there are some very modern architects who live in very old houses, and zealous advocates of modern furniture whose own homes are filled with fine old pieces.”

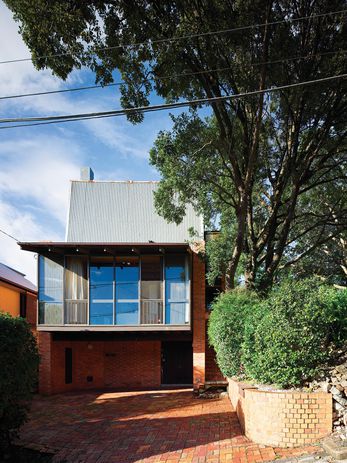

Railton House and Office (1963) in Brisbane, designed by John Railton for his own family, acted as a case in point for the architect’s critique of Queensland’s “wasteful” urban planning policy.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

More than four decades later, in 1980 , architectural theorist Léon Krier formulated a similar critique. In a photographic series entitled “Vertues privées et vices publics” (private virtues and public vices), which was published in the Bulletin des Archives d’Architecture Moderne, he opined: “It is remarkable to observe the good taste and restraint with which the most wildly innovative architects choose their own residence and workspace.” In this text, Krier mocked the different approaches that architects adopt when designing dwellings for others as opposed to designing their own homes. The former, he suggested, was far more experimental than the latter. Krier’s critique was largely directed at those modern architects involved in modern mass housing projects, such as Alison and Peter Smithson, who in the late 1960s designed Robin Hood Gardens, but who themselves (in Krier’s words) lived in a “sympathetic Italianate villa in Chelsea.”

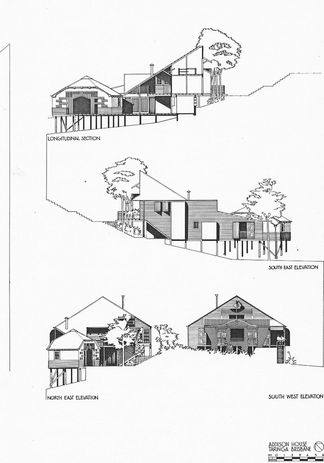

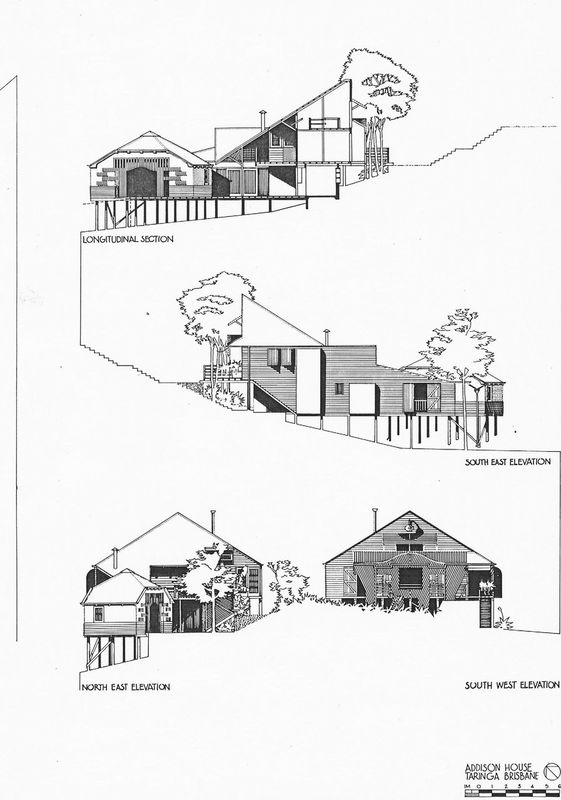

But architects of course did not and do not only experiment at the expense of others. A long tradition exists of architects designing experimental dwellings for themselves. Think of Frank Gehry’s exploded bungalow in Santa Monica ( 1978/1991 ), which is often touted as one of the first deconstructivist buildings. In Australia, Rex Addison’s 1974 house in Brisbane comes to mind, which defied the ascent of international modernism by proposing a new take on Queensland’s timber-and-tin housing tradition. These architect-houses are famous because their experimental designs challenged mainstream forms and practices within the discipline of architecture.

Addison House No. 1 (1974/1982): Rex Addison’s first project, and his own home, was pioneering in its reinterpretation of Queensland’s timber- and-tin tradition.

Image: Courtesy Rex Addison

Architects’ homes can do more than challenge the status quo within the discipline. As the conditions of designing one’s own dwelling typically allow for more far-reaching forms of experiment than is possible through commissioned work, architects, who often see themselves as social engineers, can articulate broader social, political and cultural critiques through the built form of their own houses. Moreover, when architects live in the houses they design, aesthetic objectives and ideology become inseparably entwined with the personal. The architect’s house can thus offer a rich ground for investigating “activism at home.” And yet, while the architect’s home has found significant coverage in literature, it has rarely been studied from this angle. This approach – “activism at home” – could shed light on several tensions that architects are faced with, not only when designing their own homes, but in the profession in general.

The first key tension is generated by the desire for experimentation – in service of social, political or cultural change – versus the quest for commissions. An architect’s own house is often seen as a calling card for potential clients and therefore commonly strives to be aesthetically pleasing. This tendency is most pronounced in countries with a high proportion of single-family houses, such as Australia. Here, the design of the architect’s own home augments the tension between the necessity to market the architect’s practice and the desire to experiment.

A good example is the house that architect John Railton designed for himself and his family in Brisbane in 1963. This house formulated a strong critique of Queensland’s wasteful urban planning policy. In an article published in The Telegraph newspaper on 25 March 1964, entitled “Why neglect the terrace house?” Railton criticized Queensland’s outdated urban planning legislation1 as an economically unviable housing solution. He argued that the large footprint of Queensland houses caused unfettered sprawl and increasing traffic congestion, and promoted the compact terrace house as a suitable alternative, using his own home as a case in point. While there was no direct reason why his house should be built between two largely blank masonry walls, Railton chose this unconventional approach to raise an issue and to demonstrate that this typology could be both spacious and spatially interesting.

Another tension that warrants greater attention when studying architects’ own homes results from the architect assuming a double role, as both the activist designer and the inhabitant of the house. By collapsing the roles of designer and inhabitant, the architect designs for change but also lives with(in) the vehicle – his or her house – that serves to promote, test and trial such change. In Spaces of Hope, professor of anthropology and geography David Harvey appositely explains this tension: “Imagine ourselves as architects,” he writes,

“… all armed with a wide range of capacities and powers, embedded in a physical and social world full of manifest constraints and limitations. Imagine also that we are striving to change that world. As crafty architects bent on insurgency we have to think strategically and tactically about what to change and where, about how to change what and with what tools. But we also have somehow to continue to live in this world. This is the fundamental dilemma that faces everyone interested in progressive change.”

Railton used the design of his home to demonstrate the capacity of the terrace house to be spatially interesting and a suitable alternative to sprawling dwellings.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

Harvey thus develops the notion of the “insurgent architect” – a metaphor for an embodied agent productively taking part in the transformation of everyday life worlds, including the personal sphere. Designing and living in their own home, the insurgent architect can make the personal political and is thus able to address the longstanding tension between the designer and the users of architecture.

A current example is the Nightingale model. Fed up with property developers, offshore investors and low-quality, expensive housing, Jeremy McLeod and a small group of other like-minded Australian architects joined financial forces to deliver environmentally, socially and financially – developers’ returns are capped at 15 percent – sustainable apartments. A test case was built in Melbourne in 2014 : the Commons. Featuring green power, a rooftop communal garden, a communal laundry and a car-share scheme, it demonstrated what was possible as a one-off and became immensely successful. Particularly interesting is that upon its completion, McLeod moved into an apartment in the building, along with his partner and one of her daughters. The intention was to stay for eighteen months to experience and study the pros and cons of living in such a green, community-focused building and to devise better solutions for the next Nightingale projec t – living as a form of research to which he subjected not only himself but also his family.

In today’s urban age, with rising real estate prices and growing social inequality, such insurgent, embodied practices warrant greater attention, and it is the charge of architectural writers to continuously bring into focus architecture’s activist potential – at home or elsewhere.

1. In a bid to promote public health and counteract the development of slums, the Undue Subdivision of Land Prevention Act 1885 mandated a minimum lot size of sixteen perches (404 square metres) and a minimum frontage of thirty feet (ten metres).

Source

Discussion

Published online: 20 Jun 2018

Words:

Janina Gosseye,

Isabelle Doucet

Images:

Christopher Frederick Jones,

Courtesy Rex Addison,

John Gollings

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2018