Porthole, keyhole, pothole, peephole, manhole, black hole, sinkhole, blowhole, wormhole, borehole, just some of the many words the masterclass at the RMIT Gold and Silversmithing School explored with renowned goldsmith Peter Bauhuis. The workshop was all about making, understanding and creating something that isn’t there, an absence rather than a presence. As an introduction to the world of holes, Bauhuis quoted from by Kurt Tucholsky’s short essay “The Social Psychology of Holes”:

The strangest thing about a hole is its edge. It’s still part of the Something, but it constantly overlooks the Nothing – a border guard of matter. Nothingness has no such guard; while the molecules at the edge of a hole get dizzy because they are staring into a hole, the molecules of the hole get… firmy? There’s no word for it. For our language was created by the Something people; the Hole people speak a language of their own.

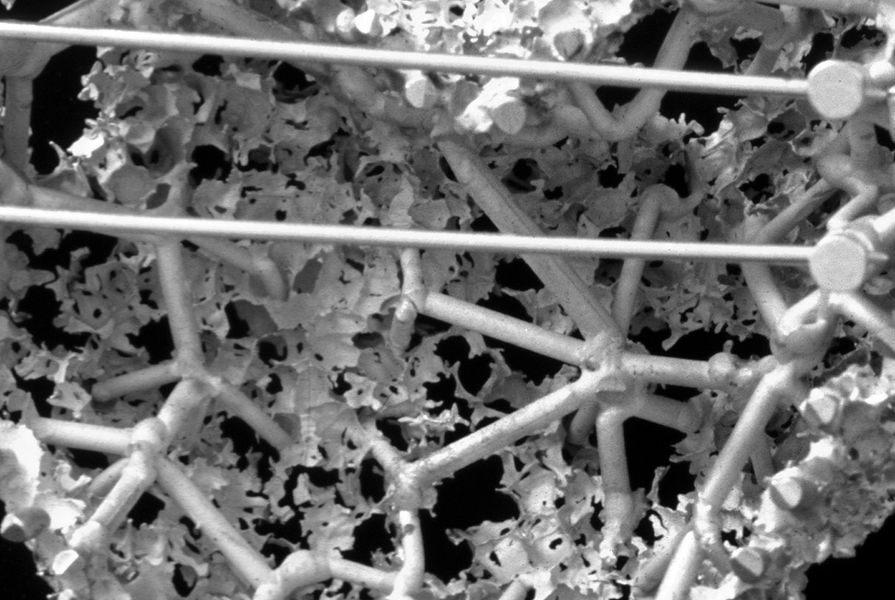

Peter Bauhuis, Simultanea; object 2014; silver alloys

Image: Peter Bauhuis

I love this text for the workshop’s flyer. It seems so relevant to the work of the architect, who must grapple with the parallel “problem” of how to design something that is much more than it seems. Unlike architecture, though, in the world of the goldsmith understanding comes through making as well as through thinking, because so much of the research and invention occurs during the process, which in the case of Bauhuis’ work is casting in gold, silver and other metals. He calls this “material work” – knowing, by means of repeated practice, how a material will behave under different conditions. He has employed this process to achieve the seemingly impossible, like the fusing of brass with silver, which he eventually accomplished in Simultanea (vessel, 2013), and to turn what is not the lightest of materials, metal, towards a visual sense of lightness, which he also succeeded in doing in his Foam Gold brooch series (1998-2001). Bauhuis’ material experiments focus on bringing together ideas and techniques with a deep understanding of the discipline and its history. This often means playing visual tricks; for example, in his current show Armillaria (Melbourne Hallimasch) at Gallery Funaki he displays a little “bronze” cup (untitled) as part of the cabinet of curiosities he fashioned from Gallery Funaki’s pristine white walls.

Peter Bauhuis’ Treasure of Kolomna, supposedly from Russia, ca. 600 AD; Bronze, copper

Image: Peter Bauhuis

The cup is part of “the Kolomna Report” – the official announcement he made of the “evidence of prehistoric cultures” found between Moscow and Oka during “a neo-scientific exploration by the Institute of Newer Archaeology”. It is part of a collection numbering more than eighty works ranging from vessels, culinary implements and jewellery suitably and meticulously painted by the artist to look like objects from the bronze-age, but suspiciously featuring such unexpected details as horizontal ridges (takeaway coffee cups?), pretzel shapes (in the form of bracelets) and, most revealing of all, the unusual bronze-age bottle opener. What is disconcerting is how readily we are willing to be persuaded by appearances – as a visitor to the gallery, I didn’t dare pick up the object to ascertain its authenticity. The artist’s play is a deadly serious commentary on the precious and the faux, the values society places on the old and the unique and our mores about appropriate behaviour in the gallery space.

Bauhuis’ objects shimmer with patinas that emphasise the presence of a natural world in-between and in-parallel with his own man-made inventions. Understanding, as he says, that “the organic is much more precise than the technical”, he lets nature do its thing and never retouches the surface of his objects once they come out of the forge. Rivulets of steam cast special lines over his “silver stones” Hearts brooches (1999) when he “mistreats” the object during the casing process. Sometimes it has taken him a year of unsuccessful casting to reproduce an effect he has stumbled across “accidentally”. In the public lecture he gave at RMIT in the week of the workshop, he presented an image of the Milky Way which for a moment I thought was a close-up of the surface of one of his Shibuichi (a silver and copper alloy) vessels, making the point that his art is about re-presenting nature – the Hallimasch organism (armillaria), for example, or the Klein Bottle, a mathematical conundrum, and making them personal, wearable, touchable and almost usable through his art. As he puts it: “a lot is possible but it must come out of the world of jewellery”. Understanding that world takes a minimum of ten years, he says. The journey for Bauhuis began at the Staatliche Zeichenakademie in Hanau then continued, after a three-year apprenticeship in a goldsmith studio, at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts under the tutelage of Otto Künzli and since 1999 in his own studio.

Klein Bottle; pendant 2014; Gold 750, 24 x 21 x 18 mm

Image: Mirei Takeuchi

From the knowledge of tradition and technical limits, which he constantly tests, Bauhuis’ work reaches into story telling (for example the brothers Grimm, also a Hanau connection); a must, he says, because the job of jewellery is to communicate. From this imperative, he has constructed a complex, interconnected world he invites us to glimpse into. The exhibition, which is designed as a cabinet of curiosities, presents his scientific interests, his collection of drawings (I particularly like the one illustrating an operation for “removing beauty from the eye of the beholder”), a few Incredible Strange Objects (ISOs, or objects that can’t be immediately identified), little paintings and newspaper articles sitting side by side with his fine vessels, necklaces, rings and bracelets.

The title of the show is Armillaria, the name of an organism that can cover nine square kilometres underground but only manifests itself in the form of tiny mushrooms above ground, is also intended as a metaphor for the complex web of connections that make up the influences, dynamics and discourse influencing his work. In the world of Bauhuis, everything is connected to everything else, in ways of course we cannot always know or maybe will never know. “We should always keep the doubt,” he says.

The mystery and the discovery, the something and the nothing, beckon us from this exhibition at Gallery Funaki.

Armillaria (Melbourne Hallimasch) by Peter Bauhuis Dates: Exhibition from February 3 to March 7, 2015 Venue: Gallery Funaki, Melbourne