|

Architect’s Statement by Alex Popov

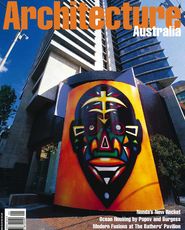

is a two-storey housing complex fronting Mona Vale Beach, on Sydney’s northern peninsula. It comprises 17 one and two-storey apartments organised in two lineal groups separated by an internal pedestrian spine. The design was developed with equal consideration given to the public amenity of the local precinct and the relationships between the apartments themselves. This scheme allows for a diverse range of apartment types sustained within a common structural framework of shallow-vaulted steel portals. It differs from the conventional approach to apartment design by breaking down the massing into separate and identifiable units that step to resolve the irregularities of the site and significant trees. Within this framework, each dwelling is highly articulated, with the layering of materials, openings and deep shadows in order to create rich and lively facades.

The proposal also addresses the concept of ‘neighbourhood’ through the site plan. Building types are separated and focused along an internal ‘street’ which provides good landscaping and a sense of suburban scale.

Comment by Lawrence Nield

What is the most important building type? It is high density, low-rise, as Kenneth Frampton has pointed out. Cities are in crisis all around the world. “The typical downtown surely which, up to 30 years ago, still presented a mixture of residential stock with secondary industry, has now become little more than a Motopian landscape dominated by tertiary industry.”

“By similar token,” he continues, “the unremitting suburbanisation of North America and the simultaneous dissolution of the nineteenth century provincial city, structured about the railroad, has been brought about by the deliberate maximization of private transport, sponsored by oil and automobile lobbies and by the corresponding contrived decline of public transport. While these symbiotic consumerist processes are at their most extreme in the US, it is clear that this tendency is to be found throughout the developed world, so much so that one is tempted to assert that if there is a single apocalyptic invention in the 20th century it is the automobile rather than the atomic bomb.”

The way to address these problems is by adequate and multi-modal public transport and more collective ecological housing, particularly low-rise, high-density housing. Successful low-rise, high-density housing is not new. It has been built in many isolated locations over 30 years and there are exemplars. One thinks of the 1960 Siedlung Halen by Atelier 5 in Switzerland and there are a number of important Australian examples, such as Lindsay and Kerry Clare’s public and private apartments outside Maroochydore. Surprisingly these vitally important building types are few.

Exemplary low-rise, high-density housing is clearly different from higher density residential units – the typical Australian ‘units’. Low-rise, high-density housing anticipates a future with networks of circulation and ways of dealing with the car or public transport. It emphasises compact low-rise development which allows it to “more than exist” in typical urban and suburban environments. It sets standards of ecologically sensitive planning. In every way it prevents urban degradation.

Alex Popov’s Rockpool housing on Mona Vale Beach is an important example of low-rise, high-density development. It also shows a way out of our urban crisis. Here, on what was four quarter-acre blocks housing at the most 16 people, there are now 17 residential apartments in one- and two-storey formats.

Its internal circulation, one can imagine, and courts could be extended as a pedestrian network back from the beach and through to the Mona Vale shops. Here is a fragment of a future city.

|