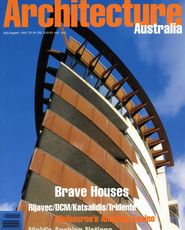

|

top Looking south from the car entrance above Looking along the ocean (south-east) facade.

More photos can be found | Photography John Gollings Review George Michell Barrie Marshall has now finished his extraordinary bunker house on Phillip Island. This windswept beach resort, some two hours drive from Melbourne, is dotted with flimsy fibro and weatherboard shacks, many elevated on spindly legs to look out over the dunes to the ocean. Marshall’s house shuns this lightweight tradition and presents an alternative approach to the beach shack. Built entirely of concrete and galvanised steel, the house has nothing of the temporary and improvised nature of the typical weekender. Marshall has conceived his family retreat as a solid construction which not merely hugs the ground but is actually hidden within as if to seek refuge from the elements. This device also guarantees that the house is effectively concealed from view. Privacy not prettiness is paramount for Marshall and his family, and this is reflected in the choice of a style that is both stern and ruthlessly elegant. There is little here of the picturesque and busy qualities of some DCM projects; rather, this is a personal exercise in monumentality and restraint conceived by Marshall for his family and friends. It is also a masterly exercise in discovery, demonstrating that severity of style need not rule out richness of architectural experience. Any visitor arriving at the house will inevitably experience a sense of disorientation as there appears to be no entrance. Only after passing through a narrow gap in what appears to be a natural rise, but which is actually an artificial mound, does the visitor come upon a square lawn that also serves as a forecourt to the house. Open to the sky, yet effectively sheltered from wind and glare, there is no pretence at suburban planting here; only unadorned concrete panels on three sides with natural scrub on top. The house, which forms the fourth side of the square, presents a similar concrete surface, broken by window openings seemingly devoid of frames. The masonry here is punctuated by shallow disc-like recesses, originally intended for coloured stones but still unfilled. These create a gridded patterning that only occasionally coordinates with the window openings. Marshall’s idea of geometry is aesthetic and fluid, rather than insistent, since it does not predetermine the position of all of the surface elements. A galvanised steel screen jutting out into the forecourt directs the visitor to the front door. To the left is a large window through which there is a tantalising glimpse of the ocean beyond. Smoke curls up from an angled, funnel-like chimney rising through the scrub on top of the roof-the first clue to any habitation. On entering the kitchen/dining room, the visitor is instantly overwhelmed by nature, for suddenly there is a dazzling panorama of rocks, sand and ocean. Unlike the concrete panels facing into the grassy square, this farther side of the house opens up in a number of fixed, sliding and louvred glass panels, some set back behind a protective colonnade. No other house is in view, nor any people other than distant surfers and fishermen well out to sea. The Marshalls, it seems, have made the oceanic wilderness their very own personal experience. Recovering from the shock of this unexpected exposure, the visitor gradually takes stock of the house interior. And what a glistening interior this turns out to be, with its polished blackened terrazzo floors and galvanised steel sheet dividers and doors. Such gleaming materials achieve an unexpected lightness of effect, capturing and filtering the external glare. The kitchen/dining room is devoid of fixtures other than a pair of stainless steel benches. But this is no rough and quasi-industrial environment; the surfaces and drawers are all meticulously detailed, especially the delicately formed, slender handles. The reflecting steel object beyond the ranges turns out to be a wheeled storage cabinet containing, among other items, the fridge. Nearby, a pivoting door gives access to the living room, which occupies the west end of the house. Other than the fireplace and a metallic bookshelf, there are no installations. Comfort and colour are achieved by Vico Magistretti armchairs and a couch, draped with colourful horseblankets. Windows frame views of the grassy court on one side and the ocean on the other; the room being seemingly suspended between two dramatically contrasting landscapes; protected and exposed. The west end of the house is taken up with bedrooms, bathrooms, laundry and a store These are conceived as discrete chambers positioned between a wall of glass offering more of the same ocean view and a corridor lit intriguingly by floor-level glass slits. Metallic panels, serving as both wall dividers and rotating doors, barely touch the floor and ceiling, which continue uninterrupted from one end of the house to the other. Angled bedheads and bathroom fittings are metallically minimal and sometimes dangerously sharp. The box-like chambers increase in size as they proceed towards the last bedroom, with the result that the corridor decreases in width. This has allowed Marshall to create a playful sequence of steel planes, one jutting out behind the other. The end bedroom, which forms a climax to the house, is provided with a telescope. Following this gaze outward, the visitor eventually proceeds towards the beach. Only when looking back is it possible to view the complete length of the house, tucked into the sandy rise and covered with earth and brush. Can this merging with nature be the beginning of a new beach house tradition? Dr George Michell trained as an architect in Melbourne and now is an author and Indian and Islamic archaeologist and historian based in London. He is collaborating with Melbourne photographer John Gollings on a book about recent Australian houses. Marshall House, Phillip Island, Victoria |