Two weeks before I was due to interview Valerio Olgiati in Sydney, I received an email from his studio. Set out in the email was a list of interview conditions.

I have interviewed a number of architects, none of whom issued preconditions. The first condition was that I attend Olgiati’s talk for the Australian Institute of Architects’ International Speaker Series. No problem there. Another condition was that I read a couple of attached articles (more on that below). One condition stipulated that I focus my questions “on Valerio and his work/architecture.”

This was surprising, as the thought of asking about anything else had never occurred to me. The only truly problematic condition was that I submit all my questions in advance, with a prescribed deadline so tight as to almost ensure non-compliance. Inevitably, the interview did not take place.

In his blog Notes on Becoming a Famous Architect, Conrad Newel attempts to deconstruct the mythology of the “starchitect.” A recent post, entitled “The deceptive paradox that is the Zumthor brand,” describes how Peter Zumthor has skilfully engaged the press in order to construct the image of an architect disinterested in publicity. Writes Newel: “Any publicist will tell you that the first rule of making a name for yourself or managing your image is: Be nice to people, but bend over backwards for the press.”

Like Zumthor, Olgiati is an autodidactic Swiss architect known for uncompromising, minimally ornamented, exactingly crafted buildings. Whereas Zumthor has recently attained mainstream success – awarded the Pritzker Prize, selected for the Serpentine Pavilion, championed by Alain de Botton – Olgiati remains a cult figure. By cult figure, I do not only mean that he enjoys a small but passionate following. There is a cult of Olgiati, made up of only the most devout of architects, a select Donald Judd-loving, Wong Kar-wai-watching, capital-A-architect crew.

One does not attract a cult following by accident. A cult must be cult-ivated, the wheat separated from the chaff. Take, for example, François Roche’s infamous 2011 letter to Sci-Arch, in which he contemptuously declines an invitation to lecture and exhibit his work. Roche did not just spurn a PR opportunity. He also posted the letter on his website, proof to his followers of unstinting personal integrity. You see, cult architects ‘bend over backwards’ for nobody.

To try to understand how Olgiati has attained his status, you might flick through El Croquis edition no.156 (2013). Here you will encounter the work of a minimalist Swiss architect more or less like any other. You might then turn to Olgiati (2012), a small, slim book containing an illustrated transcript of an Olgiati lecture, which has been published by Birkhauser in several languages. Alongside evocative imagery, the book records a series of apparently straight-faced pronouncements from the architect, of which my favourite is: “it is vital than an architect should know what food suits his or her taste.”

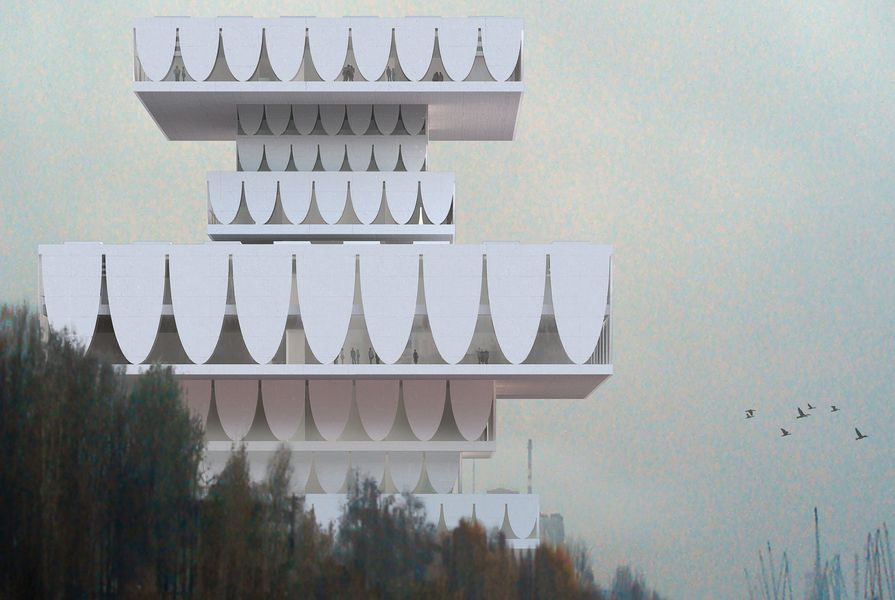

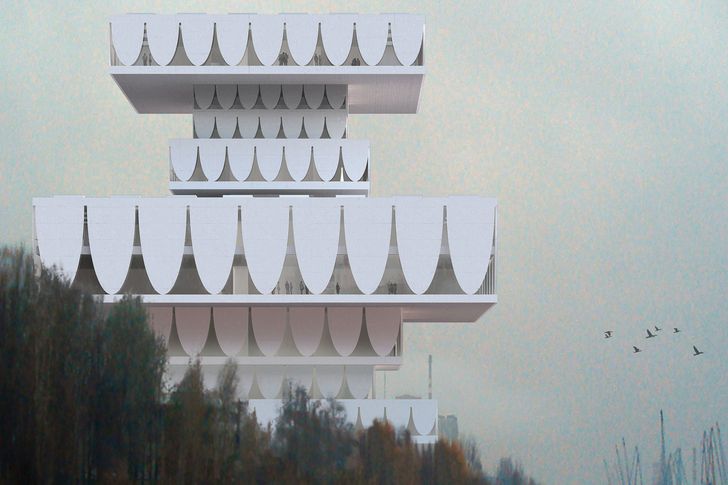

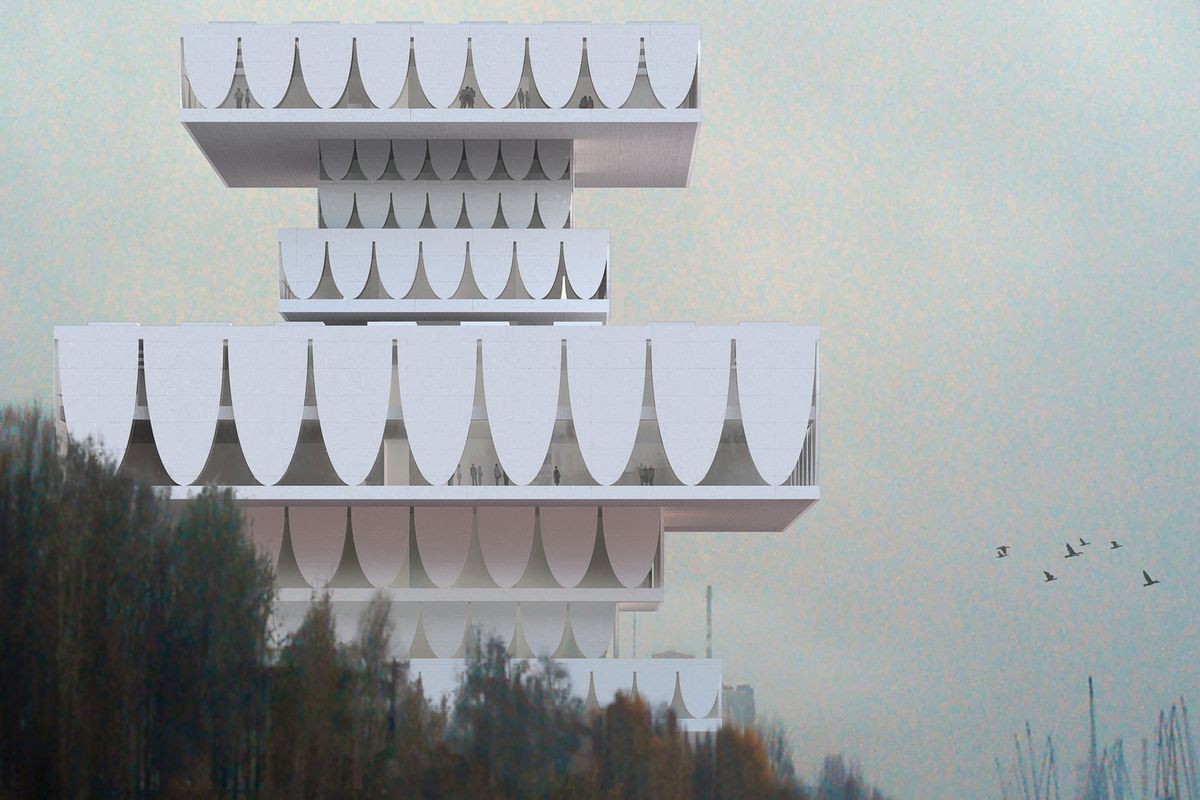

Proposed pavilion by Valerio Olgiati on the Caumasee, in Flims, Switzerland.

Image: Courtesy Meyer Dudesek Architekten

However, neither of these texts will provide as much insight into the Olgiati mythology as the articles provided by his studio as one of the listed conditions. The first of these articles, from a+u issue 507, is a narcolepsy-inducing interview in which Markus Breitschmid asks Olgiati a single question: ” how is it possible for a building to exist in only one way and no other way if the architect does not believe in anything?,” and elicits a 2,574 word response. “I learned that the only way to make architecture that is not symbolic and not historical is to make buildings that are purely architectural,” claims Olgiati. If you can believe that architecture is capable of negating or transcending any symbolic and historical interpretation, you’re likely to accept that Olgiati’s work is pure architecture.

The other emailed article, written by expatriate Australian architect Peter Wilson for AA Files 65, is most illuminating. Entitled “Valerio Olgiati: a visitation,” Wilson’s article plunges headlong into “the recent media success of the Olgiati oeuvre.” Writes Wilson: “for Olgiati, as for Le Corbusier, discourse is marshalled by a sophisticated understanding and instrumentalising of mass media,” which has “generated legions of fans, who now make uninvited pilgrimages to Flims, outmanoeuvring motion-sensor security lights as they scale the Olgiati perimeter wall.”

One can only speculate why this article, in which Olgiati is both venerated and ridiculed, was considered by his own studio as necessary preparation for an interview.

Visiting Center Swiss National Park, Zernez, Switzerland.

Image: Javier Miguel Verme

Man behind myth

Valerio Olgiati.

Image: Courtesty Archive Olgiati

Finally, it was time to meet the man himself, albeit at a distance. The doyens of Sydney architecture – including Glenn Murcutt, Wendy Lewin, Richard Johnson, Neil Durbach, Camilla Block and Peter Stutchbury – assembled under an appropriately concrete-grey sky at the National Institute of Dramatic Art Parade Theatre for Olgiati’s lecture.

With groomed grey hair and near-transparent glasses, the middle-aged Olgiati dresses in the loose-fitting black garb of a sensei. But there are none of the dour pronouncements of the printed-word Olgiati. His kind, lilting voice conveys an unexpected charm. “Architecture is mainly something about how one looks at the world,” he tells us, launching into his first-person narrative while Tamara, his wife and business partner, remains seated with the audience.

From the outset, it is clear how much his father, Rudolf Olgiati, has shaped that outlook. The elder Olgiati was a revered figure whose work merged Modernist principles with vernacular Swiss architecture. Olgiati junior describes growing up in his father’s shadow, “confronted” by the 500-year-old objects his father collected and stashed in the barn. While Olgiati still lives in the family home, he refers to his work as a reaction against that parental legacy.

Accordingly, he has amassed his own collection, a set of fifty-five images which he calls an “Iconographic Autobiography.” Ranging from shadowy temple interiors to abstract art, archaic plans to classic houses, these images are shown at every opportunity alongside Ogliati’s ouevre. The effect is seductive, a mix-tape of motifs that all architects enjoy.

The seduction continues with a selection of projects, the first of which is the Bardill Studio in Scharans, Switzerland, one of Olgiati’s best known works. Offering the preface “this sounds like a mystification but is actually true,” he tells us that the studio’s dramatically sparse volume was a consequence of a budget shortfall. We are then told that each of the cast-in-situ flower decals that adorn the studio walls was individually hand-carved by a local craftsman. “We did not even consider a robot to do this,” says Olgiati, only deepening the mystification.

Bardill Studio in Scharans, Switzerland.

Image: Courtesty Archive Olgiati

Hushed oohs and aahs accompany photographs of gorgeous red concrete walls, and continue into the next project, a skillion-roofed school auditorium. A succession of precise, utterly convincing concrete details confirms Olgiati’s reputation as the Swiss masterchef of reinforced concrete. But again the narrative falters.

The auditorium has been sited to create a “public space” within a larger campus, but presents an impenetrable twelve-metre high wall to its surroundings. Of his choice to create a monolithic concrete volume, Olgiati says, “I like to build in unities,” which fails to explain why he bisects the space with a huge diagonal column and a network of smaller beams.

Like the music studio, the auditorium is depicted without occupants. Unlike the small studio, which seemed tranquil in its emptiness, the cavernous auditorium is dark and forbidding. There is no discussion of the use and enjoyment of these buildings, only material considerations, structural forces, and the fascination of the object.

At this point, I begin to understand how Wilson’s article could be both complimentary and disparaging. An apartment building in Zug, Switzerland, features: “red concrete like in a catacomb. Everything is red. They are surrounded by this red architecture.”

What sounds like a Kubrick-esque nightmare is, in fact, spectacular. Reminiscent of Kahn’s Salk Institute, relentless concrete is enlivened by a rhythmic geometry of shadow and void. Less forgiving is the house planned for the architect and his wife on a large tract of land in rural Portugal. Not only is the house enclosed by a high wall with a lone window, but bedrooms are reached via a colonic forty-metre-long tract of corridor. Sitting on the concrete sofa in the concrete living room, says Olgiati, “you feel like you are at the end of the earth.”

“One can think of a building in the head,” claims the architect, “one does not need sketches or lots of plans to explain an architectural idea.” So committed to this idea is Olgiati that he refuses to adapt to the necessities of program, use or context. Sometimes his buildings are starkly elegant. Often they are just stark.

The architect’s architect

Any architectural approach this dogmatic and all-encompassing requires enormous effort. Ultimately, one wants to know: what motivates this effort? What is the id that operates behind this ego? Angelo Candalepas, creative director of the International Speaker Series, attempted to pose this question, in a sense, when he asked: “do you design spaces for spirituality or enjoyment?” Olgiati feigned confusion. “What is the difference between spirituality and enjoyment? I don’t know how to answer this question. Right now I just make everything in either white concrete or red concrete.”

Perm Museum XXI, Russia.

Image: Total Real AG

This reaction brought huge laughs. How charming his reaction and childlike wonder seemed. However, shortly afterwards, Olgiati shifted gear to share an anecdote about Zumthor. Inviting comparison with his illustrious countryman, Olgiati described how Zumthor had lost a competition because he lacked awareness of the financial implications of his ideas. “He made everything wrong!”, joyfully exclaimed the man who a minute earlier could only think in terms of concrete, white or red.

Despite his obsessive-compulsive fondness for perfect squares and platonic solids (“I would find it strange to build with bricks, because for me the building would have to be a multiplication of the same brick dimension”), I suspect Olgiati is not the creature of instinct he would have us believe. Born and bred in his father’s office, his is a career of calculated provocation. From the seductive imagery of the “Iconographic Autobiography,” to his “pure architecture” creed, his work has been painstakingly tailored to inculcate other architects.

His buildings are alternately bleak and beautiful. Inside, however, there is only room for one. The removal of furniture, fixtures, even occupants, ensures that nothing distracts from the author’s voice.

Like Alberto Campo Baeza, a guest of the International Speaker Series in 2012, Olgiati craves control. Both architects have spent their lives in pursuit of that perfect moment beloved by photographers – the stillness of dawn, pools of shadow, an empty lawn – hoping to represent it forever in their buildings. Although this vision is at odds with that other contemporary utopia, the solar flare-enhanced architectural rendering, it is equally unreal.

Read architect Andrew Burns’ perspective on the talk, the mytholgy and the architecture of Olgiati here.