The Australian Islamic Centre in Newport, an inner-west suburb of Melbourne, eschews the architectural strategy of most recent mosques built in Australia – it features none of the readily recognizable signifiers of dome, pointed arches and minarets that typically signal “mosque” in urban peripheries around the country. Instead it confidently assumes a cool, contemporary language of glass and concrete, enlivened with pools and a surprising roofscape of gold-painted sheet-metal lanterns.

The architects of the complex are Glenn Murcutt and Hakan Elevli. In my meeting with Elevli, he notes that it was Murcutt who “took the community on a journey” that resulted in such a radical design. It was also Murcutt who questioned how necessary the conventions were and who found alternatives and realized them in a contemporary manner.

Thus, instead of a minaret, the symbol of the crescent moon is held aloft to the side of the entry court of the building on a vast triangular extension of the side wall, a delicate gold sickle. Instead of the dome architecturally standing in for the firmament, those triangular lanterns admit light, its colour varied by orientation: gold glazing oriented to the east, green to the north, red to the west, blue to the south. They cast triangles and bars of colour onto the floor of the prayer hall, producing a field of shapes that differ with the position of the sun and the condition of the sky. It’s poetic in its simplicity.

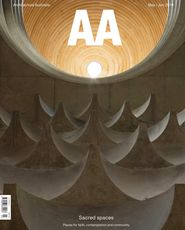

In place of a dome, the building features a flat roof punctured with a series of coloured lanterns that admit natural light to the prayer hall.

Image: Veeral Patel

These features are the most beguiling elements of what is volumetrically quite a simple building. There is a generous covered entry at the front of the building, fronted by a paved forecourt with six deciduous Indian bead trees (Melia azedarach). At the sides of this entry are stations for ablutions and timber shelves for shoes. Once the building is complete, there will also be pools of water flanking the outer edges of this space.

The prayer hall for women is accessible by a lift and stairs on the northern side of the entry – Elevli is circumspect about this separation of the sexes, saying that the community is more comfortable with it. The balconied women’s space in the mosque occupies the building volume above the entry, and it connects to a gymnasium for women in the adjacent building complex to the north. But the separation is not complete – in the interior, there is a stair at the southern end of the building that directly connects men’s and women’s spaces. The women’s hall, on the building’s outer walls to the east and partly to the north and south, is clad with glazing and louvres, producing on the inside a luminous but opaque enclosure. On the outside, the cladding of these glazed walls is more demonstrative – closely set vertical glass blades that suggest transparency without quite performing it. But at night, when lit, this no doubt produces another lantern-like effect.

The prayer hall is delimited by cast concrete walls to the north, south and west. Elevli mentions that these caused some concern among the community – why were they not using the rapid construction of the tilt concrete slabs of so many warehouses to be found in the industrial district just to the west of the building? They were persuaded to go with the slower technology of the in-situ concrete walls, and the brut character of the concrete shows on the interior and the exterior. At the south-east corner of the building, the high wall that carries the crescent is battered at its base to make obvious the texture of the concrete.

A vast, triangular wall projecting from the southern wall and topped with a crescent moon proffers an alternative to the traditional minaret.

Image: Veeral Patel

Glazing connects the prayer hall to the entry space alongside. This opens the prayer hall to the future public zone of parkland to the east – another Murcutt innovation to make the main space of the mosque visually open. This is more symbolic than performative: while there are several entry points, the building’s distance from the street keeps it discreet for the present. Nevertheless, this gesture is an important one – the glazing to the east is answered by glazing at the lower part of the west wall, the qibla . Visible through this is another pool, along the western edge of the building. When I visit, this is complete with aquatic plants making it something of undeniable loveliness, delimited though it is – the textures of rushes, lotus and surface-hugging water greenery are a close-up visual delight. Beyond this pool is another wall – it as if the perimeter enclosure has been sliced horizontally and the lower portion pulled out.

The internal effect of this gesture is to draw one’s eyes to the west of the space, to the water and wall beyond it. The dreary extent of Melbourne’s western suburbs – they go on forever – is mitigated by the attention the building draws to the confined pool, brilliantly lit by the sky, a linear paradise with a luxuriance of aquatic plants. Their green is a striking contrast to the concrete surfaces and the neutral colours of the prayer hall. At the centre of the qibla is the mihrab , realized as a robust concrete niche projecting into the pool, with a concrete rostrum counter-projecting forward. There is an inscription cast into the mihrab ’s outer wall and another inscription in the wall above.

Support for the ceiling of the prayer hall is apparently offered by a grid of steel columns, elaborated with flanges that step out halfway up. With the horizontal extension implied by the glass to east and west this produces the effect of a kind of downward spatial compression.

The roof is populated by a geometric sequence of ninety-six lanterns. Each lantern was assembled on the floor of the prayer hall before installation.

Image: Tobias Titz

The mosque is only one part of the facilities envisaged for this site. To the north will be community spaces, a library, classrooms and a residence for the imam, as yet but partly built. To the east, the adjacent site will be restored as a public park. This again signals the difference between this mosque and so many of its suburban predecessors, surrounded as they too often are by car parks that maroon the building in a sea of asphalt. Here, the public domain when complete will come right up to the mosque’s forecourt. Cars are dealt with in a linear strip at the southern edge of the parkland, with the intention that a row of trees will offer shade; they will also veil the cars’ visual clutter. Otherwise, vehicles are hidden behind the building.

The close adjacency of the public park also suggests that the mosque is confident of its open relation to the community around it – I was surprised that the prayer hall was unlocked when I arrived, and while waiting for the architect I was generously welcomed by the imam. Viewed from the east at a distance, the glazed walls of the women’s prayer hall and the hooded lanterns on top of the building give the building a gleaming white and gold appearance. Seeing it across the currently dishevelled park-to-be, it’s curiously festive.

Although complete in its most significant architectural gestures, the Australian Islamic Centre is still somewhat unfinished. To get this far has taken the architects and community more than a decade, with progress contingent on the ability of the clients to raise money from month to month. They have been motivated by a wish for a contemporary building to welcome existing community members and a wider public. This has been achieved. The architects have been patient. Apart from the buildings to the north and the restoration of the parkland to be completed, there are still book racks to install in the prayer hall, furnishings to finish the mihrab , and chairs to get right for community members with limited mobility. There are also broken pavers to replace in the forecourt and the flanking pools to realize.

Such signs of incompletion should not diminish our sense of astonishment at this building, however. When I visited, there was another stranger there, an Australian architect based in Singapore who came to see the building because of Murcutt’s reputation. He was alarmed and disappointed that the building was so lacking in finished polish. He said he felt like taking up tools to finish it himself. But the big things are there to be seen through the incomplete details, and they are simple and good. And there is the coloured light and the beautiful linear pool.

Credits

- Project

- Australian Islamic Centre of Newport

- Architect

-

Glenn Murcutt and Elevli Plus

- Consultants

-

Energy consultant

GHD

Landscape architect Tract Consultants

Services engineer NJM Consulting

Structural engineer Dome Consulting

Traffic consultant Cardno Grogan Richards

- Site Details

-

Location

Newport,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Public / cultural

Type Religious

Source

Project

Published online: 31 Jul 2019

Words:

Paul Walker

Images:

Gene Kehoe,

Glenn Murcutt,

Tobias Titz,

Veeral Patel

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2019