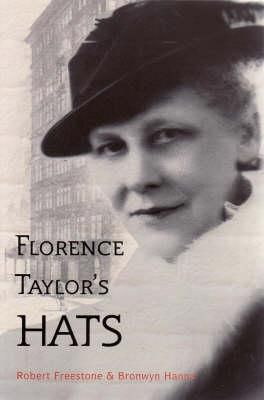

Florence Taylor.

Image: State Library of New South Wales

Florence Taylor was a person of many hats – literally and metaphorically, as authors Robert Freestone and Bronwyn Hanna reveal in their book Florence Taylor’s Hats. She was Australia’s first qualified female architect, as well as a town planning advocate, a writer, editor, publisher and successful businesswoman.

She was also the first Australian woman to qualify as an engineer and reputedly the first Australian woman to fly a glider.

Her achievements earned her an OBE in 1939 and a CBE in 1961. She was nominated to become a face of Australia’s new decimal currency in 1965, along with the likes of opera performer Dame Nellie Melba.

In 2001, at the centenary of Australia’s federation in 2001, she was recognized as one of 250 most notable women in Australian history.

“Florence Taylor was undeniably a woman of extraordinary energy, courage and achievement,” the authors say.

“We offer a particular focus on Florence’s varying contributions to the built environment as a woman within the then highly masculinized 20th century professions of architecture, building, town planning and publishing.”

Florence Taylor’s Hats.

Image: Halstead Press

Florence Taylor was born in 1879, and in 1899 she enrolled in an architecture course at Sydney Technical College (STC). In 1900 she began working in a clerical position in the Parramatta offices of architect Francis Ernest Stowe.

She attended STC at night time, and although she failed several subjects in her first year and some teachers “never came near as if she was a python,” she was soon receiving good marks and winning awards.

She completed her formal training 1904, becoming the first professionally qualified woman architect in Australia.

From 1900 to 1905 undertook her articles with Edward Skelton Garton and in 1906 she began working for John Burcham Clamp.

In 1907, she applied to become the first woman member of the New South Wales Institute of Architects, a move that caused much controversy with an apparent majority of members vehemently opposing her admission. A special meeting was held to discuss the matter on 21 March, where Florence’s employer John Clamp gave a speech advocating for Florence, declaring “Why, she can design a place while an ordinary draughtsman is sharpening his pencil!”

A “barrage of hate” leveled at her, as well as possible threats pertaining to a rumored affair with her former employer Francis Stowe, however, would lead to her withdrawing her nomination.

“Florence was vulnerable not just because she was a woman, but she was a young, attractive and single woman with little social standing,” write Freestone and Hanna.

“She was a single woman whose sexuality could be constructed as a threat to the morality of the profession.”

Florence married George Taylor in 1907, subsequently giving up her career as an architect and building a publishing empire with her husband.

In 1920, long after she had ceased working as an architect, the NSW Institute of Architects passed an unanimous motion to accept women members. Florence then became its first woman member. She lambasted the Institute in her oral examination. As her sister Annis Parsons recalled in a 1933 memoir:

“I don’t know why you are subjecting me to this scrutiny now, which is tantamount to persecution. Years ago when I was an orphan with sisters to keep I was denied entry, though I was fully qualified, and at a time when membership would have placed the hallmark upon my architectural reputation. Now it seems nothing to me for I am successful without your help. It does, however, mean something for my sex, which is why I am linking up.”

Few records remain of her architectural work but what was published was met with disdain and condescension, including in the pages of the institute journal Art and Architecture.

George Taylor died in 1928 and Florence was at the helm of their publishing business until her retirement in 1961. She was editor of Building magazine for more than half a century. The business also published Construction, Property Owner (which later became Australian Home and then Commonwealth Home), as well as Harmony, a music magazine.

The authors of the book note that throughout her career, Florence’s femininity and feminism permeated all of her endeavours. She was a staunch supporter of women and their achievements.

But despite all her achievements, Florence Taylor’s public perception would be eclipsed by her appearance – made all the more distinctive by her “flamboyant hats.” The incessant focus on her sartorial accessories draws parallels to how the British prime minister Margaret Thatcher was often talked about for her handbags.

One profile of her written by journalist Ray Castle in the Daily Telegraph (30 December, 1959), could shame even 60 Minutes reporter Charles Wooley and his now infamous “sexist and creepy” interview with New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern.

Castle wrote: “It would be hard to find anyone more feminine than Mrs Florence Mary Taylor. And almost impossible to find any woman with less feminine interests. When I dropped in to see Mrs Florence Taylor on her 80th birthday yesterday, I was struck by her beautiful perfume, her frivolous hat, her soft feminine dress. But immediately she began talking about tunnels, bridges, high density building and car parks.”

The authors of the book described the many articles written about Florence as presenting her as “a gracious and elegant lady doing a ‘man’s job.’”

Even her biographer Kerwin Maegraith noted her “attractiveness.”

Florence Taylor owned 32 hats which she later donated to the Feminist Club. Freestone and Hanna said, “We see Florence Taylor’s flamboyant hats as providing an eloquent metaphor for her somewhat strident show of femininity in encountering these challenges.”

“Did her flamboyant femininity work against her credibility as a designer and spokesperson for numerous causes?” the authors asked. “Did her hats somehow block lines of communication, rendering people deaf to what she was trying to say? Was she too easily dismissed as an elitist or an eccentric because of her appearance?”

They conclude: “She was variously a pioneer and a conservative, an egotist and a confidante, a workaholic and a style setter, a ratbag, a philanthropist, a tyrant and a heroine.”

Florence Taylor’s Hats is published by Halstead Press.