‘On’ Monumentality

Commonwealth Place, by Durbach Block, Old Parliament House, New Parliament House. Image: Tim Linkins.

Tent Embassy. Image: Christopher Vernon.

Ball-Eastaway House by Glenn Murcutt. Image: Anthony Browell.

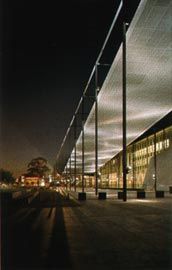

Swanston Street, with RMIT’s Building 8, by Edmond and Corrigan, and Storey Hall by Ashton Raggatt McDougall. Image: John Gollings.

Line of Load Miners Memorial by the University of South Australia. Image: Sam Noonan.

The National Museum of Australia by Ashton Raggatt McDougall and Robert Peck von Hartel Trethowan. Image: Peter Bennetts.

Scientia by MGT. Image: John Gollings.

Sidney Myer Music Bowl by Yuncken Freeman, refurbished by Greg Burgess Architects. Image: John Gollings.

Melbourne Museum by Denton Corker Marshall. Image: John Gollings.

In a short but elegant essay, “On the ‘On’ of On Photography”, Meaghan Morris observes that “A text ‘on’ a topic is not necessarily as text ‘about’.” Ons, she writes, are “the smooth swirls which are not straight lines that bind things together”. This sense of the different purpose and effect of “on” is useful to keep in mind when considering On Monumentality, a recent symposium organised by the RAIA NSW Chapter, UNSW, UTS and the University of Sydney. On Monumentality was not really about monumentality instead the event ranged widely over the theme, which became an opportunity to think around and through many issues pertinent to contemporary architecture.

For the organisers, On Monumentality – subtitled Place, Representation and the Public Realm – was a chance to discuss public buildings and spaces. They pointed to the diminished importance of the public realm and to the challenge that the dominance of international capital presents to the interpretation and meaning of public and civic architecture. They asked, “What is the nature of monumental architecture at the beginning of the twenty-first century?” and “What reflections of ourselves do Australian civic and public projects offer?” ›› Some participants engaged directly with these questions while others problematised them by exploring related issues. Some were interested in how ideas of monumentality might help them proceed when making buildings and how public buildings and spaces might monumentalise civic life; others pointed to the impossibility of any kind of unified collective meaning. Some addressed the complex history of the term itself, while others felt that the topic no longer has any useful currency. Conceptions of the city and of the public were contested. Works discussed included Richard Leplastrier’s Volunteers’ Memorial, the NMA, the NGA, Federation Square, Commonwealth Place, Old Parliament House, New Parliament House, the Tent Embassy, Storey Hall, houses by Murcutt, RMIT Building 8, the Broken Hill Miners’ Memorial and East Circular Quay. Participants spoke about monuments, the monumental, monumentality, memorials and more. These are not the same thing and the slippage between terms was both interesting and frustrating. At times the frames of reference became so wide that all specificity and meaning seemed to dissolve. At these moments Morris’s smooth swirling “ons” could be pulled into play to help find ways around this complexity.

The other part of the event name had specific architectural resonance. “Monumentality” alludes to postwar anxieties about Modernism, and to Sigfried Giedion’s famous call for a “new monumentality” and the debates that followed from it. Functionalism, Giedion argued, was not enough: “People desire buildings that represent their social, ceremonial and community life. They want buildings to be more than a functional fulfilment. They seek the expression of their aspirations in monumentality…. Monumentality springs from the eternal need of people to make symbols.” Although Giedion coined the term, the influence of another participant in the post-war discourse – Louis Kahn – was perhaps more strongly felt throughout the Sydney event. His commitment to monumentality as a way of expressing the civic role of public buildings was, for some, a way to address the contemporary problems of public space. Yet, as Maryam Gusheh pointed out, this is problematic. The debates of the 1940s about monumentality need to be historically and geographically situated. One cannot import them to twenty-first century Australia without reworking them (and, as Paul Walker suggested, without rethinking “Australia”). For a number of participants Gianni Vattimo’s more recent work on monumentality and “weak thought” offered a way to begin doing this.

The event was intended to “construct a bridge between theory and practice”, but there were also many other differences at play. Indeed it was tempting to set up lots of oppositions – place/discourse, theory/practice, academic/practitioner, phenomenology/post-structuralism, city as setting for public life/city as collection of signs, Melbourne/Sydney, monumentality as the way forward/monumentality as redundant, tectonic/surface, monuments as the expression of shared values/the impossibility of such shared values, and so on – but this is too easy. This array of differences operated not as a line-up of opposing positions, but as a complex network of tensions between all kinds of contested ideas and ideals. It is in this play of tensions that space might be found for things to happen – for thinking “on”.

The symposium began with David Leatherbarrow’s elegant, eloquent keynote address.

He deployed Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Savings Fund Society Building to argue that monumental buildings are alternately impressive and recessive, both figure and ground.

Inconspicuously conspicuous, they have a kind of double temporality – engaged in the city, the monumental building is also distant from it. The following day was split into two. The morning session, “Theory, Culture, Place”, outlined a “broader theoretical and cultural context”. The afternoon contained project-based sessions under the banner “Critical Review and Further Directions” followed by a closing panel discussion. This made sense, but as Xing Ruan asked, is the gap between theory and practice also a monument? Some of the day’s most interesting and difficult questions were raised in the morning session, but they were not returned to in the afternoon.

The event also felt like a monument to the architectural establishment. All the speakers were well worth hearing, but it would have been good to hear some less expected voices.

Compelling issues were raised by the “newer voices” of the three academic respondents in the “theory” session. I would have also been good to hear what younger practitioners, or those working on the margins of architecture or landscape, might have to say on this topic.

Caroline Pidcock asked twice why it was that the only women invited to speak were academics. The second time, this question was addressed to the closing panel of “distinguished architects and practitioners”, who were asked what role they saw for women in the making of monumental architecture. For the most part their responses were, for me, depressing and unsettling – dangerously close to the traps of essentialism.

It was a densely packed day in which both too much and not enough was said. Perhaps the various participants simply need more practice talking with each other. There are few formal opportunities for academics and practitioners to talk together around ideas and issues that concern architecture as both discipline and practice. For me this was the most important thing. Regardless of topic, this opportunity to talk “on” architecture, across academia and practice, is important. We need more such events.

The symposium raised many questions. For me the most compelling were not about monumentality, but come from this particular exploration “on” it. Why do women find a voice in academia (and other “marginal” locations) more easily than practice? How might the occupants of the Tent Embassy, and those it tries to represent, find a voice in the “conflict of representations” that is Australia, and in things that are built in the country’s name? Who, more broadly is represented and who is left out in various attempts to represent civic life? Is such a singular thing as “Australian culture” possible anyway? If a unified collective experience is not possible how do we proceed? Such questions cannot be answered, but they are worth re-iterating. As we talk about other things, they are questions on which we, collectively, should speculate and work more.

Justine Clark

Against Monumentality

One of the persistent erosions of our civic life has been the tendency for certain architects and their patrons to impose a level of so-called “monumentality” onto the commissions with which they have been entrusted. Unfortunately, this regressive modus operandi has an energy largely generated by an underlying conservatism which has, historically, consistently broached all political ideologies.

For example, the cancellation, in 1962, of an already subscribed architectural competition for a new National Gallery and the subsequent awarding of this commission to Roy Grounds was a key event in the curtailing of Melbourne’s experimental Modernism. Grounds, clearly to my mind punching way above his weight, abandoned any pretence at finding an appropriate expression for one of the world’s greatest art collections, and lurched full-tilt into a crepuscular monumentalism reminiscent of a 60s US Balkan consulate by that other compromised Modernist, Edward Durrell Stone. Melbourne got a simplistic, moribund pile: a generation later the whole sorry assembly has to be reworked to provide a functional gallery.

Grounds’ design would not have survived the first cull of a decent architectural competition, such bombast being an anathema to the sort of jurors that the NGV’s then director, Eric Westbrook, would have engaged. However, Westbrook had resigned in disgust and the city fathers, far from dismissing Grounds, went on to hand him the whole Arts Centre complex, and Melbourne is forever the poorer.

Compare this situation with the “winging it” daring of Barry Patten and Angel Immitorf’s beautiful 1956 design for the Sidney Myer Music Bowl only just across the way in the Melbourne Botanic Gardens.

No ponderous monumentalism here; instead, a coherent work of modern architecture, which from its unveiling was proclaimed a true monument and adornment of this elegant city. Despite Frederick Romberg’s attempt to dismiss Patten and Immitorf as derivative, the people of Melbourne embraced this masterpiece by two very young architects, and today it is as exhilarating as it was way back in the 50s. We can only imagine what sort of National Gallery would have been forthcoming had Westbrook’s ill-fated competition proceeded. Perhaps it would have been a demonstration of the first rule of a radically modern architectural culture, to wit, that the best architects are always going to be the ones you have never heard of, ›› So, the issue of monumentality is, I believe, fundamentally flawed. Well, maybe not if your preferences run to the works of architects such as Paul Ludwig Troost, whose 1936 Das Haus der Deutschen Kunst in Munich exhibits an uncomfortable family resemblance to Grounds’ morbid range along St Kilda Road.

Monumentality will always be the province of the power elites and their supplicant architects. Who would believe otherwise?

This is not a new dilemma. It has always been with us, and is one of the ethical divides that many hold against architecture as a morally corrupted vocation. The old saw – that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely – has often been cited in relation to the insensate destruction of neighbourhoods, regions and even whole cultures in the pursuit of monumentalist architectural projects.

As an invited participant in Sydney’s October symposium, “On Monumentality”, I attended with intuitive caution that this could well be an uncomfortable experience. It was: the acceptance of intention rather than necessity as the basis for the declaration of a monument, and the concomitant assumption that monuments can be defined a priori, are very much reflections of the tedious self-referencing within Australia’s socalled “Design Culture”.

Peter Myers

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Jan 2003

Words:

Justine Clark,

Peter Myers

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2003