<b>REVIEW</b> Sandra Kaji-O’Grady <b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> John Gollings Anthony Browell

Front elevation to Anzac Parade.

Oblique view of the front facade reveals the sophisticated abstraction of the structure and fenestration.

The decked courtyard, located between the two wings, at podium level.

Twilight view of the courtyard and the disciplined internal building facade.

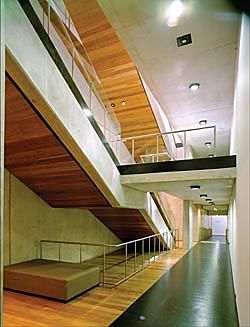

The building’s east and west edges are devoted to circulation, resulting in elegant communal spaces.

The wide timber entry stair, rising from Anzac Parade.

One of two long stairs, which connect the lower floors at the building’s north and south edges.Photography credits 01, 02, 04 John Gollings. 03, 05–07 Anthony Browell.

The L5 building at UNSW by Bligh Voller Nield is flawless, both in execution and conception.

Refined material resolution and an accurate response to programmatic requirements is what we have come to expect from this practice. The flawlessness of conception is something else, and I will return to it, as it poses significant challenges to critical interpretation, indeed, to engagement by any audience.

Situated across from the main campus of UNSW on the western side of Anzac Parade, the building’s street facade is sufficiently graphic to withstand the reductive gaze of passing traffic. Project director Lawrence Nield is suspicious of the discourse around the “branding” of institutions, yet the abstract grid of structure and fenestration – akin to an Agnes Martin painting – readily translates into the two-dimensional medium of the publicity photograph. At the same time, the street facade offers deep concrete sills at just the right height for perching and waiting, along with legible entrances to its two main institutions – New South Global’s Institute of Languages and Foundation Studies, and National Information and Computer Technology Australia (NICTA), a federally funded computer research institution. The two institutions operate independently and have very different corporate cultures and activities. The first, which conducts short courses that prepare international students for university studies in Australia, needs a shopfront and administration, teaching and examination spaces. The second involves research students and staff working on highly specialized collaborative projects. If the scrawls on white boards around their space are any indication, their work involves experimental mathematics obscure to the layperson.

Andrew Cortese, the other project director, caricatures this client as being made up of the sort of individuals who work intensely all night.

The building area of 12,400 square metres is organized into two wings, around a decked communal courtyard at podium level. To reach the courtyard from Anzac Parade there is a generous 10.8-metre-wide flight of timber stairs rising over four metres. The deck will eventually be enlivened by a cafe and furnishings, but the courtyard, by Sue Barnsley Design, is currently sparsely vegetated with clumps of bamboo that offer no relief from the sun.

Below it are two levels of classrooms with panelled walls that are removed each examination cycle to form a larger space. Without daylight or views some of these classrooms could be claustrophobic, but the students are undertaking short courses and move around the building between different classes, a design studio and a small library. Moving around is easy. The organization of the programmatic elements is legible from all parts of the building, with vertical circulation between floors situated at the north and south ends, adjacent to all the services and bathroom facilities. Along the east-west axis, circulation is, unusually for this type of building, located at the perimeter with offices or classrooms pulled back from the edge. This enables both social encounters and complex, changing light qualities.

The facades are ventilated and equipped with woven aluminium blinds that are automatically triggered by heat, and can also be manually operated to eliminate glare. Floor-to-floor heights vary from 2.7 to 4.9 metres and the ceilings are raised at the edges – as a result these perimeter circulation spaces are elegant, even lofty, spaces.

As a solution to a brief for generic office and classroom space suitable to entrepreneurial facilities that will inevitably change as demand shifts, L5 is an undeniably masterful solution. The building’s controlled detailing and legible organization is the product of a mature team of architects confident in their approach and unswayed by fashion.

But there is something else going on here that leads to my inability to open the work to interpretation. This is an architecture without ambiguity or doubt and devoid of symbolic references or contextual clues. Cortese explains that its compositional principle is that of radiant geometry. Everything, from the spacing of the structural concrete blades that delineate the facade to the spacing of the pigeonholes in the office common area, is in a proportional relationship of three. In this adherence to an internally consistent system, the building compares more closely to the work of Hiromi Fujii than it does to Tadao Ando, whose use of white off-form in situ concrete was a model for the architects. Briefly (and mistakenly) renowned in the 80s as the Japanese Eisenman, Fujii was greatly interested in the architectural effects of repetitive or serial systems of composition on authorship and experience. Fujii described the consequences of using predetermined compositional rules as anti-humanist, since a system – an epistemological machine – is established that is independent of human occupation or involvement. L5 adheres to a neutral logic that suppresses the expressive gesture and the signature flourish. Indeed, if rigorously followed the method precludes the widening or narrowing of a space or element for reasons outside of the compositional driver. Serial systems, when used in musical composition by Pierre Boulez and others in the Darmstadt circle in the 1950s, were accused by their detractors as being cerebral and unlistenable.

Adopted in the visual arts by Mel Bochner and Sol LeWitt in the late 1960s as antidote to the excesses of American Abstract Expressionism, they were described as solipsistic and cool. Bochner and LeWitt were confident that their work left the critic with nothing to do, since there were no deeper meanings to be reprised, no art historical references to be made, no decisions to be puzzled over, no metaphors to be invented. As LeWitt put it in his famous 1967 manifesto against illusionism and representational art, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” in Artforum, “What you see is what you see”.

BVN has worked closely with their clients, with the local climate, site and materiality. As a result, L5 is in no danger of solipsism, nor can it be entirely cerebral. This is not a work that subordinates functional requirements to formal ideals, since the mathematical proportioning system operates at an architectural scale. Yet the overall effect is of an austere beauty, the beauty of mathematics. Whatever the physiological experience, such an effect is an ancillary result rather than a primary ambition. It pursues the Kantian beauty of disinterest, of the coolly intellectual, the complete and anonymous, rather than the beauty of the sensual and expressive. This building does not represent anything – not the history of the site, nor the programme, not the structure, and definitely not the personalities of the architects. Nield insists that substance is the essence of this project, indeed that it is the essence of architecture, yet materials are used here to achieve an abstraction that is indifferent to their tactile or tectonic qualities. I find that substance here is used neutrally, its quiddity is beside the point; there is no “signature” material. This is not to say that materiality is neglected, for to achieve this degree of leanness requires extraordinary commitment and control. Even the bamboo in the courtyard appears regulated and contained. This is a building that invites intellectual contemplation and as such suits the NICTA folk particularly well.

For the international students, its clarity may be ironically at odds with the inexplicable illogic of the English language and Australian culture they encounter therein. DR SANDRA KAJI-O’GRADY IS HEAD OF THE ARCHITECTURE SCHOOL AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, SYDNEY.

BUILDING L5, UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES ›› Architect Bligh Voller Nield, Sydney––project directors Andrew Cortese, Lawrence Nield; project architect Ian Goodbury; project team Matthew Bennett, Craig Burns, Namaste Burrell, Kelvin Tam; NICTA Interiors Nikki Fine, Sandra Loeschke, Marcus Trimble.Managing contractor Lipman. Building facade engineer Connell Mott MacDonald. Structural engineer Taylor Thompson Whitting.Mechanical and environmental engineer Steensen Varming.Electrical engineer IT & C Services.Hydraulic engineer Sparks & Partners.Landscape architect Sue Barnsley Design.Cost monitor Project Cost Planning.BCA consultant Stephen Grubits & Associates.Communications consultant UNSW Communications.Acoustic engineer Richard Heggie Associates.Client University of New South Wales.