I believe it was Peter Cook who said that innovation in architecture often happens at the peripheries and is subsequently appropriated by the centre. I expect he was referring to the creative and provocative output of some young architects from Graz, Austria and Basel, Switzerland practising in the 1960s and 70s; quirky projects from the 1980s and 90s scattered throughout Los Angeles’s fringe suburbs of Santa Monica, Venice and Culver City; and his later enthusiasm for projects in Melbourne. For a few architects in Perth, it was, at the time, an appealing observation. Could the West contribute something of value? Let’s face it, this place was certainly on an edge, a long way from some centre, and today the tyranny of distance is still operative.

A new project by JCY Architects and Urban Designers just might be one of these influential fringe projects. Ngoolark – also known as Building B34 – is the Student Services Building at Edith Cowan University’s (ECU) Joondalup Campus, on the outer reaches of Perth’s sprawling suburbs.

ECU’s Joondalup Campus is set in idyllic bushland under a big, bright sky. Rejuvenated by fresh ocean breezes, campus life here is carried out in spacious, shady environs animated with the sunlight dappled through the tall eucalypts. Inspired by this setting, Libby Guj, design principal at JCY, has conceived for this young campus an impressive “building.” Any visitor would easily recognize that Ngoolark is more than a building; it is equally a landscape, a terrain, a meeting place and a symbol. With a designer’s insight, her characteristic enthusiasm and a real passion for educational architecture, Guj, with her team, has carefully negotiated spatial and functional relationships to consolidate a physical and social focal point for the campus masterplan. The immediate attraction of the new Student Services Building lies in its placemaking contribution to campus life and its success is achieved in several ways.

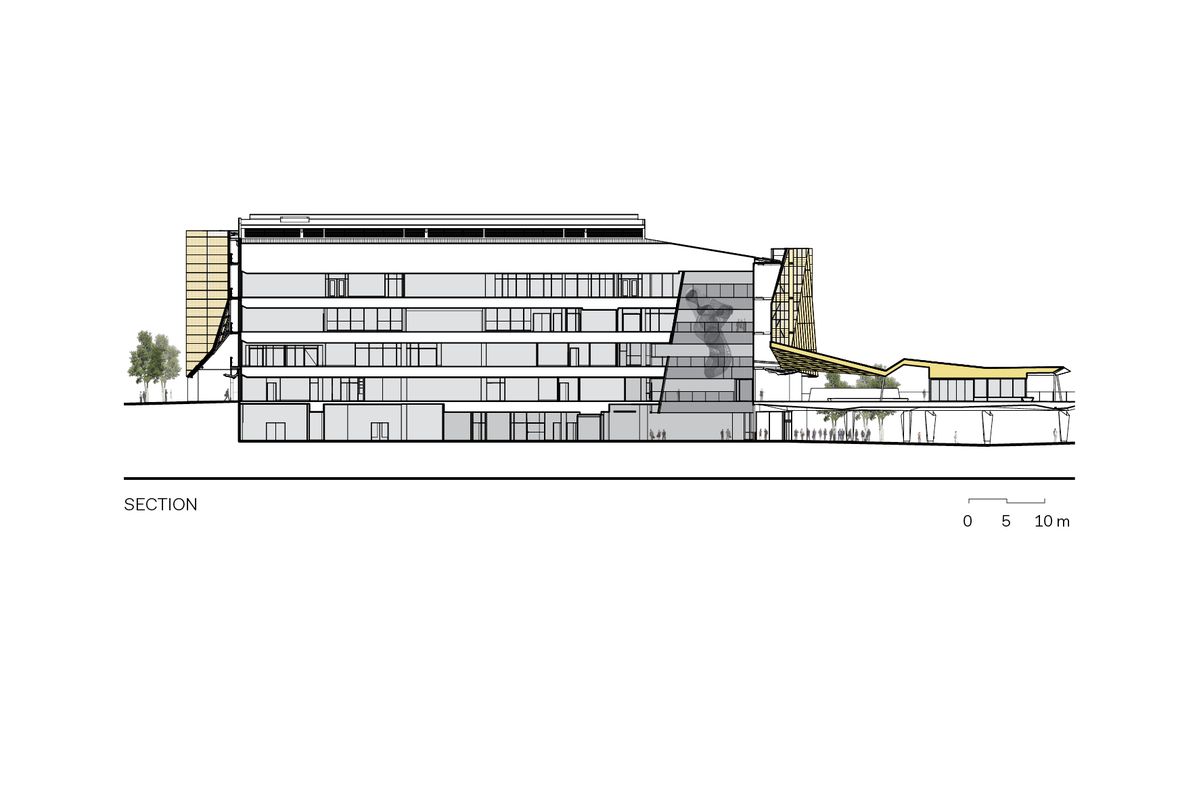

The “big move” is the facade treatment of the five-level building – a loose-fitting, gold-anodized, perforated aluminium veil that envelops the form.

Image: Peter Bennetts

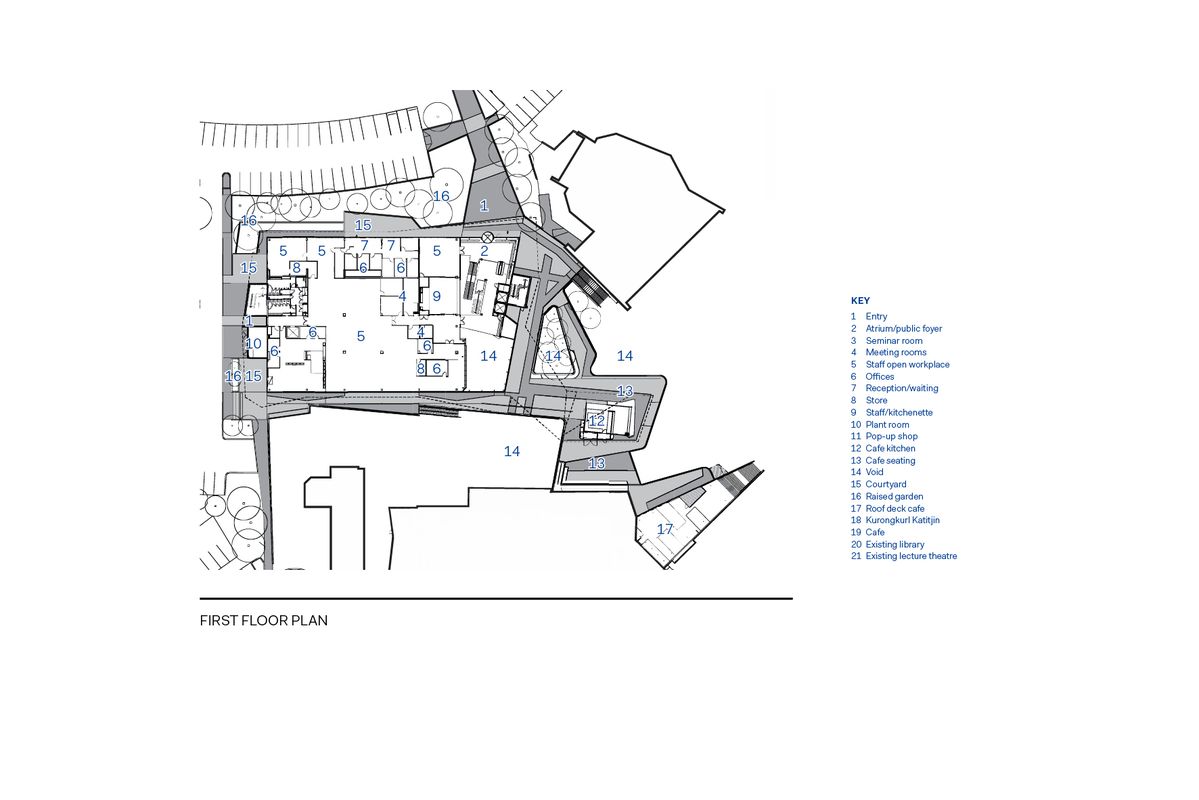

Located in a former non-site, a non-place at the edge of a bitumen carpark between the library and a lecture theatre, Ngoolark cleverly navigates a six-metre level change with a large, meandering, double-level podium. This generously scaled deck, furnished with seating, planting and lighting, provides pedestrians with convenient and easily negotiated horizontal and vertical links to neighbouring buildings. The podium’s sculpted edges, balustrades and voids afford pedestrians views and glimpses of the forum below and the landscape beyond.

Set within the podium is a small pavilion that functions as a pop-up shop at the lower level and a student cafe above. Its inviting informality draws on fully operable glass walls and integrated inside/outside seating under a generous covered walkway, a tether line that zigzags back to the upper-level entry and grand atrium. The podium, a key ordering device handled with confidence and finesse, is configured as a popular social activator.

Describing the podium as “meandering” is warranted as the design’s references to a billabong and creek are not lost, either in plan or when experienced in the round. Extended from existing pathways, the podium floods around the end of the building, and cascades down the level difference and over the gently undulating topography below, filling the territory between buildings and eroding a cave-like formation at the lower level. The gently undulating and graphically lined paving resembles a seasonally dry riverbed marked with rings from last season’s water pools. Openings in the podium above allow sunlight and breezes into the cave, softening the bright sunlight and nurturing the landscape. Along the journey, raised planters form small islands lush with native plants and trees. Cast concrete seats are like abstracted trunks and boulders left along the banks of a watercourse.

The podium’s soffit and structural columns are a sculptural delight. Faceted, grooved, angled, splayed, twisted, displaced, eroded, fractured, they are made even more impressive by their crafted execution. The excellent formwork and high-quality concrete are an exception for Perth and a credit to the trades involved.

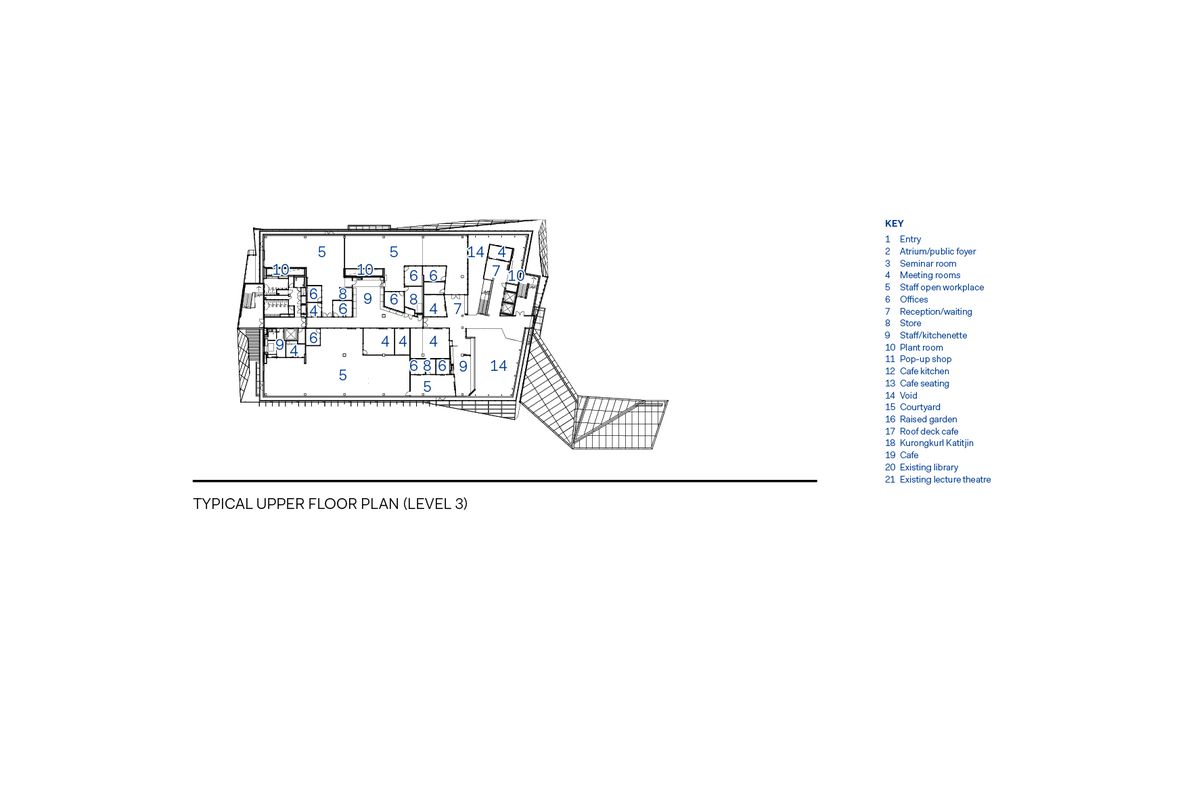

The language of facets, grooves and acute angles found on the exterior of the building also extends to the treatment of the interior.

Image: Peter Bennetts

What was a typical space between campus buildings is now a d elightfully attractive place. With organic forms and a fluid sense of space, this public forum also functions as the forecourt to Ngoolark’s lower-level entry, the library and the lecture theatre. Further activated by the cafe and pop-up shop, this busy node doubles as the campus’s market square. It’s the place to be and to be seen.

In addition to the expected program for a student services facility – administration, meeting and seminar rooms, enrolments, counselling, careers and guild services – Ngoolark includes a small area for an Indigenous study group known as Kurongkurl Katitjin. Notably, the architects facilitated the inclusion of these rooms and a small landscaped courtyard into the brief. Through an informal, open and inclusive process of consultation and engagement, some noteworthy outcomes have been achieved that have helped reconcile relationships between the university and the Kurongkurl Katitjin community. At the group’s request, the vice-chancellor adopted “Ngoolark” as the building’s name. Buoyed by a sense of ownership, Aboriginal elders and community members, some of whom travelled from Queensland and other distant places, opened the building with a traditional smoking ceremony followed by dancing, moving speeches and general festivities.

Architecture at its best illuminates our sense of being human, alive and part of something grander than oneself. Architecture emerges from creative engagement with community and is always a function of relationships between people. And the way to bring vitality into architecture is to give it energy in the form of new information and re-descriptions of shared conditions. Creating architectural experience begins in, and evolves through, meaningful dialogue.

Graphically lined paving on the ground level resembles a dry riverbed, with concrete seats that look like trunks and boulders left along the banks of a river.

Image: Peter Bennetts

In this respect, there is an increasingly prevalent trend evident in Western Australian architectural expression. It is now common practice for designers to ground the symbolic and expressive substance of their conceptions in references to the state’s geography, Indigenous religious belief (often that which is related to place) and native flora and fauna. The same source material is predominant in public art commissions, almost to the point of being a prerequisite.

The new 60,000-seat Perth Stadium in its expansive landscape setting, the Swan River pedestrian bridge, Yagan Square (Perth city’s new civic place), the subterranean bus port’s entry/exit portals, recent projects in Kings Park, aspects of Elizabeth Quay and, in a more abstracted manner, Perth Arena are all indebted to these themes. The University of Western Australia’s pending Indigenous Studies Centre is sure to follow suit, and a glance at the Western Australian Museum’s website suggests the forthcoming designs for its new home will pay homage to the same subject matter. And all of these projects, and several others, will include substantial public art commissions of equal complicity.

JCY’s design for Ngoolark is no exception. Essentially, this is a generic five-level office building with some rotated planimetric geometry at the entry end deployed to displace stairs and a few “pods” to create casual relationships, a common gesture in contemporary architecture appropriate to this building’s user groups. The big move is the loose-fitting metallic wrapping that envelops the perimeter glazing. Doubling as a climatic modifier, the gold-anodized perforated aluminium veil gives Ngoolark a most commanding presence. The brilliant golden panels are a deliberate reference to the luminous petalled wings of local butterfly species. Set against the beautiful olive green tree canopies, the building’s folded, pleated and sliced facade glares and shimmers in the bright sun and glows pink and bronze through the day’s changing light conditions. It’s alive and jumping.

The shimmering golden panels of the building’s facade reference the luminous wings of local butterfly species.

Image: Peter Bennetts

“Ngoolark” is the Nyoongar name for Carnaby’s black cockatoo. The native bird’s subtly patterned breast plumage, photographically isolated, digitally pixelated and increased in scale, has become the basis for the facade’s perforated panels and the patterned carpet tiles used through much of the interior. A similar process generated the ceramic frit pattern applied to the glazing that defines the impressive atrium. Outside, a small courtyard designated Ngala Karla (a Nyoongar phrase meaning “Our Home Fires”) is enclosed with a weather-resistant steel screen that features laser-cut flame shapes. Set among the low-lying plants and below the eucalypt canopy, this figurative ensemble interprets the remarkable rebirth that follows a bushfire’s wild destruction.

There is much more to this building. There are technical and contractual achievements, and there are many more stories and representational connections that require a much longer review to elucidate. This is a heterotopic work with a strong authorial voice. It was created out of passion fuelled by a fertile imagination and a lot of commitment. Experience tells me, as a local practitioner, that Ngoolark was not financially profitable for the consultants or contractors, as works of this calibre are very difficult to achieve in Western Australia, a condition that is something of a crisis for the local profession and ultimately the urban environment.

With characteristic defiance, Guj has led her team and the contractors to a project that shows the value of thoughtful and well- executed architecture, and that design can work at many levels and elevate reality above the flatness of facts and function to deliver engaging and meaningful places. Ngoolark is at the forefront of a locally emerging architecture that has popular appeal for people with quite different needs, interests and sensibilities. And it shows that this can be done at the fringe.

Credits

- Project

- Ngoolark

- Architect

- JCY Architects and Urban Designers

Perth, WA, Australia

- Project Team

- ibby Guj, Will Thomson, Scott McConn, Clare Porter, Glenn Russell, Madeleine Hug, Jason Welten, James Bolger, Eka Pujianto, Suzanne Morris, Fionna Walker-Hart, Rob Ramsay

- Consultants

-

Acoustic engineer

Gabriels Environmental Design

Artworks Andrew Stumpfel, Sohan Ariel Hayes

BCA consultant John Massey Group

Contractor PACT Construction

ESD consultant Umow Lai

Facade consultant Arup

Height safety Altura

Hydraulic and fire services engineer SPP Group

Landscape architect Plan E

Mechanical and electrical engineers Wood & Grieve Engineers

Project manager NS Projects

Public art coordinator Andra Kins

Structural and civil engineer BG&E

- Site Details

-

Location

Joondalup,

Perth,

WA,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2015

Category Education

Type Universities / colleges

Source

Project

Published online: 24 Nov 2016

Words:

Geoff Warn

Images:

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2016